Ana Paula Cordeiro

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo: We met while working together with Amber McMillan on a devotional guide for the pilgrimages I was undertaking starting in 2004. This is when I witnessed your commitment to the art of bookmaking. Can you talk about the relationship between heart and brain, affect and intellect in what you do?

Ana Paula Cordeiro: By both nature and nurture, I am more emotional than rational. I came from Bahia, Brazil—people know about my home even though they don't know it, for it is the birthplace of much iconic Brazilian music. Caetano Veloso was my father's classmate in elementary school. In Bahia we excel in music and performing arts so much, but so much, it casts a shadow over visual arts. I grew up knowing nothing about working with my hands—there was a tinge of prejudice to this, as the closest thing are the "crafts" made by illiterate indigenous communities for tourists, and how women without college education make their pocket money while taking care of the household. I was among the first ones in my father's extended family to go to college. The burden of expectation was heavy on my shoulders to consolidate as a middle class professional.

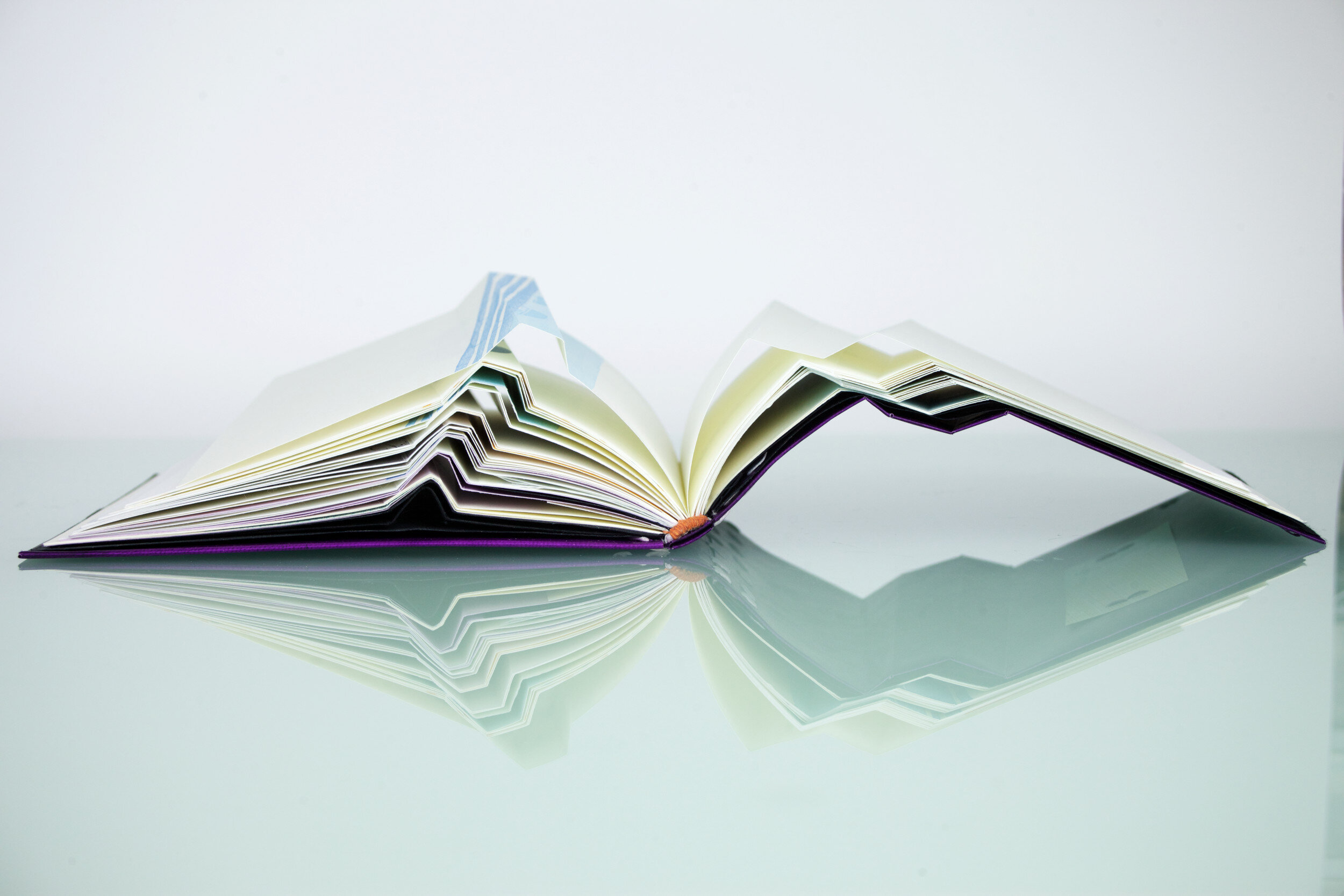

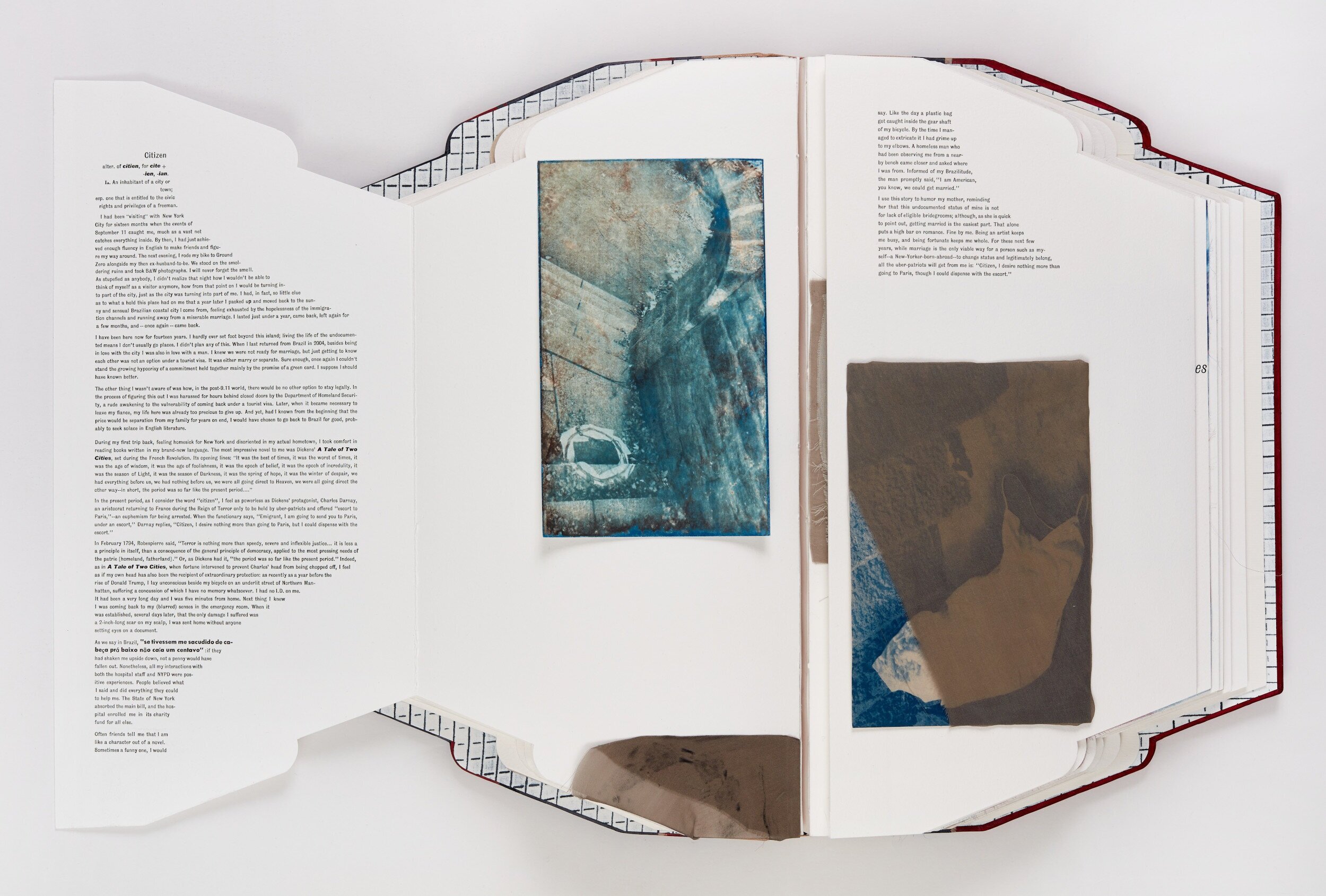

Coming to New York and falling into The Center for Book Arts’s rabbit hole was a radical and extremely transformative experience, something I was desperately seeking without even knowing it existed. Book production in Brazil was illegal during colonial times, we only got to experience it as a thing made by machines at an industrial scale. To develop skills that could combine intellect with intuition, mind with matter, metaphor with material—I was immediately stricken, my first years at The Center for Book Arts were like those of an addict. On top of a natural intellectual affinity with the medium, the community embraced me with such warmth and generosity I couldn't help but instantly feel at home. Book arts people, in my experience, were insulated from the jadedness inflicted upon other artistic circles during the ’80s and ’90s. It is not the kind of thing someone would make for the sake of centrifugal forces, like fame and fortune. Only the centripetal sheer love for the medium holds it together. I am not a competitive person. It is not about being shy—I can be feisty and pick a fight with gusto when I must. But I never had it in me to take things away from others. It took a truly nourishing environment for me to flourish. That, along with having left a loving home for the great unknown… New York, that has always welcomed me, but there is no escaping the fact that I am an immigrant. There is a work by Kimi Hanauer that anchors well my answer to your question. Hanauer says, “To those who carry traditions of exile, the weight of survival, the audacity to still be tender…”

NDERE: Ana, when I think of you, pigeons, bats, doves, swans, and squirrels come to my mind. So this conversation might meander between all of these. I hope you don’t mind!

APC: To this day I haven't handled a swan— bummer! But all the others you bet I did, including the bat. Plus a goose. I am happy you brought this up because this something many people find not natural or even acceptable. I am one of those extremists who can unglue mice from traps and open windows to let insects out. There are stories in the family about all the broken animals that I brought home as soon as I could walk, to my parents’ distress. I made my dad give up hunting when I was four or five.

NDERE: Tell me about some of the encounters you have had with non-human animals and how these might have made it into the pages of your books.

APC: Animal abuse can get me incensed to the point of losing my reason, so much so that I made a conscious decision to detach myself from the front lines and instead infiltrate as a "civilian." It is my belief that the only way I can impart anything to anyone is by example. "All knowledge is experience." Supposedly Brazilians are fervid Catholics (yeah right), but I never believed in Catechism. My work is not about imparting personal ethics. I can only walk the walk. My common ground between animal advocacy and art-making is the burning, quite frankly, almost unreasonable passion behind it, a capacity to throw myself into things that are against my best interest. At some point, much to my contentment, I realized that not only people find that inspiring, but that somehow, if not by all, surely by many, this is an almost palpable quality that can be felt when someone handles an object I made.

NDERE: How would you say your creative praxis might converse with the Earth? After all, books are made from trees.

APC: I have been making an effort to think of the Earth and its inhabitants as one thing, us humans inclusive. I have read so many times about the burden of individualism versus the progressive expansion of the very notion of self. Under these lenses, as water is one element and fire another, greed is but a force of nature, and generosity is another. And we are like dust particles caught on those vast magnetic fields. So the oil executive who has committed crimes against humanity is a particle, like the salmon going upstream. And someone like Greta Thunberg is a force to be reckoned with, as is the bear waiting by the river. All of that is Earth, and Earth is going through extraordinary times of transition in all its facets—the atmosphere, the oceans, the soil, and there is the toxicity in the shape of crude oil that comes from within, awaiting a purge.

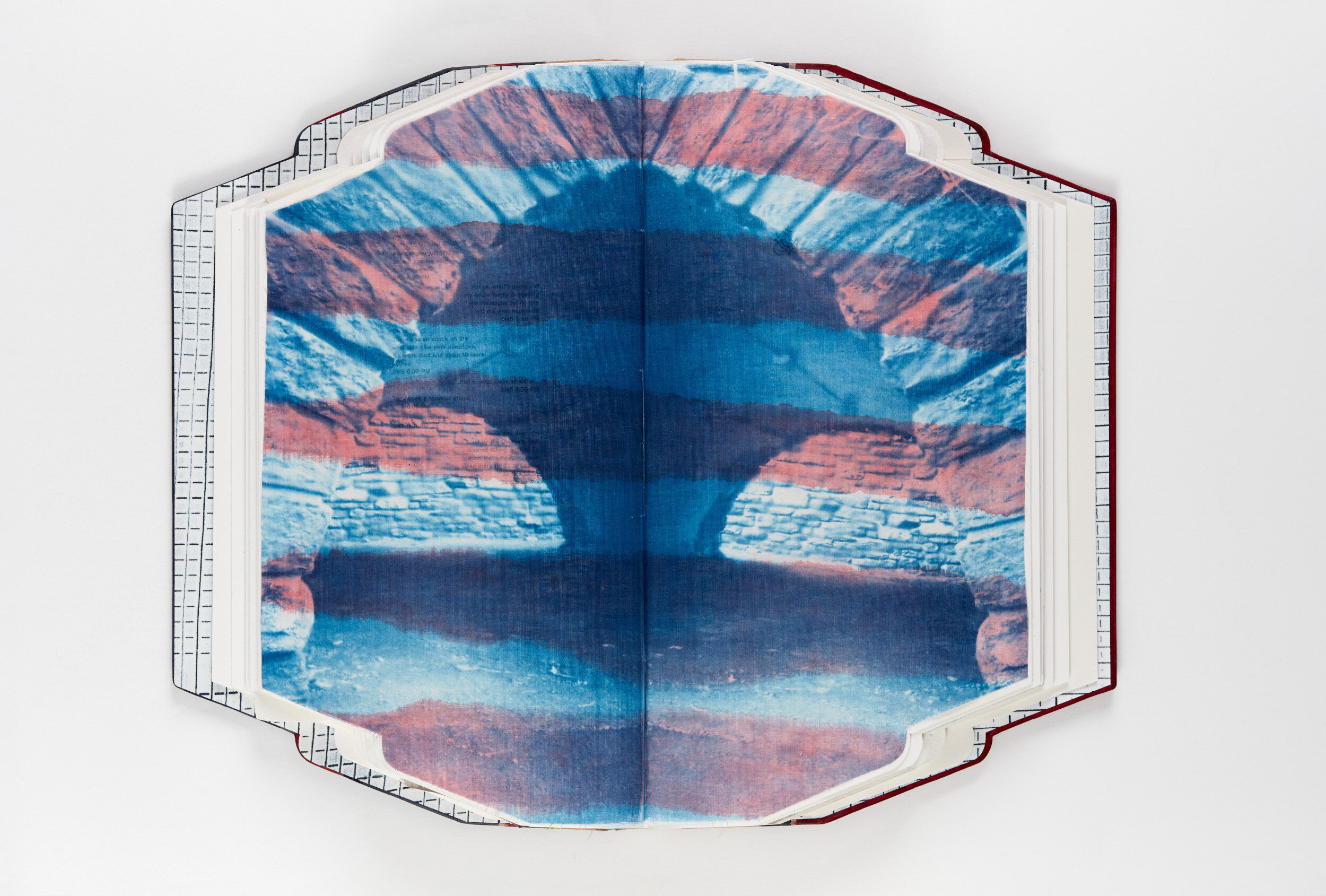

There is a Vedic concept called Indra's net that explains it more eloquently than I possibly can. I am just going to copy and paste it here, “Far away in the heavenly abode of the great god Indra, there is a wonderful net which has been hung by some cunning artificer in such a manner that it stretches out infinitely in all directions. In accordance with the extravagant tastes of deities, the artificer has hung a single glittering jewel in each ‘eye’ of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number. There hang the jewels, glittering ‘like’ stars in the first magnitude, a wonderful sight to behold. If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring.” So, to your question: my work is what makes me whole. Because tree and animal, paper and skin, hands and mind—it is all interconnected, as it is content and reader. When I am desperate about the environmental crisis and feel acutely how doing my work is BS next to it, I can only think about those things. And resign to this humbling project of making myself whole. Because that is my place in the net, and if I manage to do it right, it will reflect rightly on all other glittering jewels that hang in there.

NDERE: Have any of your books spoken to you? And what have they said?

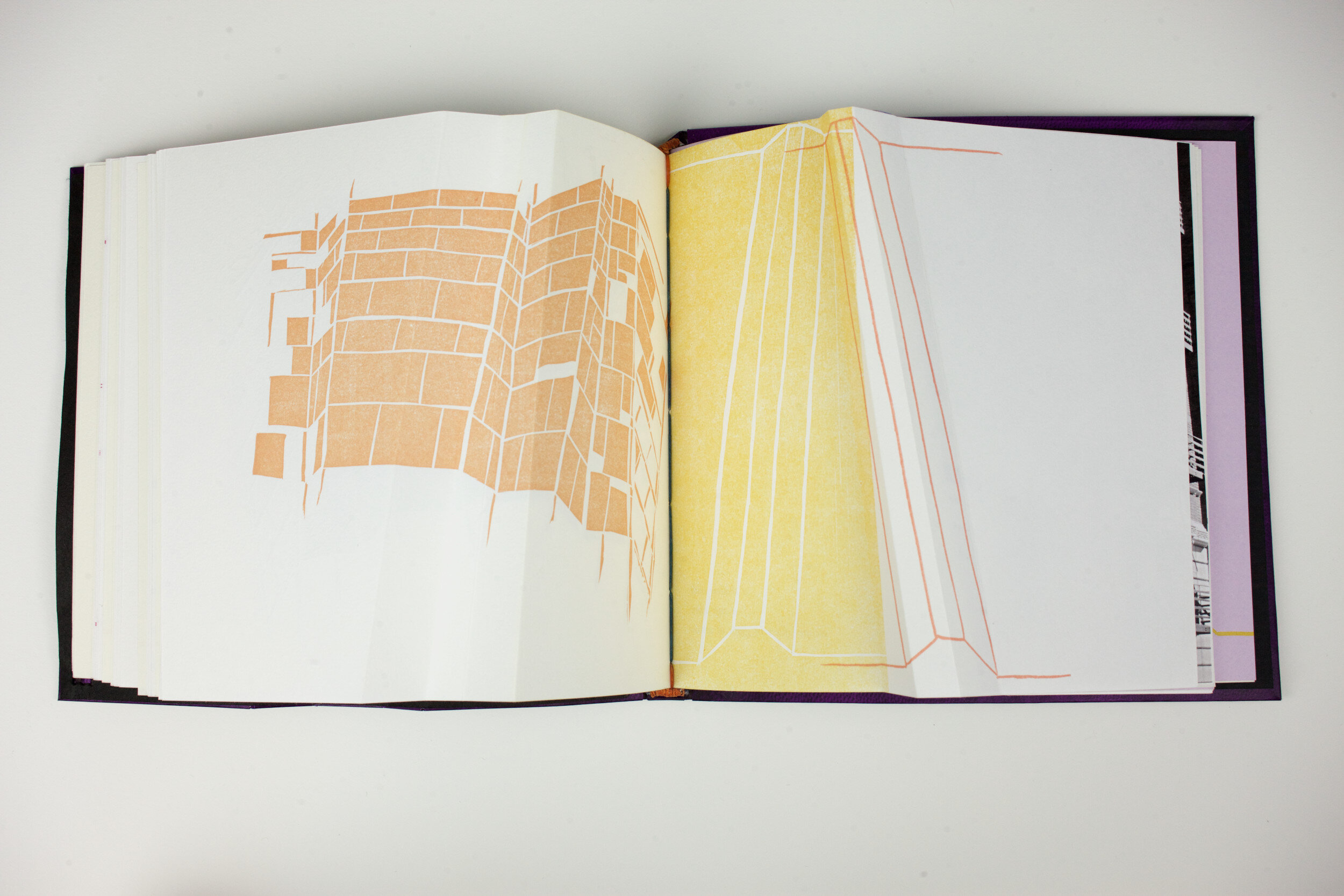

APC: I am utterly process-oriented. It all starts with an aspiration, a mess of journals, and an idea of shape. It's a distressing place, quite confusing and not too attractive. Then the thing itself gives me clues. “This is missing.” “That doesn't belong.” It is an ongoing dialogue, and it is also something that ends when it ends. I don't even feel that I have much to say about it. The work and the circumstances say it all; I am just putting it together.

NDERE: I do not always perceive all art works as living. To be honest with you, some of what I come across is cleverly articulated, but dead, energy-wise. What kind of energetic involvement would you say arises for you at the moment of shaping books? Where is healing in your practice, or how do you practice healing while making covers, folding pages, and sculpting spines?

APC: I hear you. So much of what is out there has been made sexy as a statement only to materialize dull in substance. Energy comes from many places, and the mind is only one of them. Unlike many people, I believe repetitive manual labor is actually liberating. I have one of those brains that will not give itself a break, and finding a groove that is guided by skill & muscle memory sets my mind free from being in charge. Working on an edition is said to be meditative. I guess that is part of it. But going beyond that, I would say manual work is a very fertile ground for problem solving and authenticity. It stimulates peripheral thinking.

NDERE: You approached me recently about a potential collaboration dealing with the making of a sacred book. For me, the ideal “Bible” would have no words. It would be blank. Yet this would be a book to be interpreted by those who might encounter it and listen to its pages carefully. What form would this book take for you? Can you describe it in terms of texture, volume, weight, color…?

APC: That is a tall order. I love your idea, although I myself wouldn't be able to set about on such a thing as only one book. But I will borrow one from Mario Quintana, a Brazilian poet, writer, and children's author who translated Virginia Woolf and Marcel Proust into Portuguese. For him, the most perfect book would be the one with very large margins, so readers and children would have space to add their own drawings and words and what not, and those would become part of the book.

NDERE: Can you pull a quote from one of your books to end this Q&I? Thank you for this.

APC: “ because flotsam gets caught in the gutter,

because folds have a dimension,

because open folios look like wings.

because people can despise what they can't understand,

because they themselves couldn't care less.

because they are so humble because they are so proud.

because it has hidden parts and private recesses.

because that which is pressed between two covers can be better reviled as a waste of space, because it can be revered as a sacred place.

because holding the book you are reading requires self-possession, which is something that asks to be let go of in the fashion of flickering screens.

because i would rather not fall apart.”

A runaway from the Advertising industry, Ana Paula Cordeiro's path was driven by the need to develop a set of skills for translating the mental into the multidimensional. Set in New York City from the early 2000s, and weaving through photography, The Center for Book Arts, and the Women's Studio Workshop, this thread has become recently secured as a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grantee. Prominent collections hold her artist-book-centered work, a highly personal practice that finds counterpoint in collaborative immersions, such as co-organizing the exhibition Introspective Collective, and contributing to a book about bookmaking called Bookforms.

Ana Paula Cordeiro related links: website / Instagram