LINDA: NICOLÁS, YOU ARE STANDING ON A VERY INTERESTING GROUND RIGHT NOW...THE GROUND OF ART AND THE GROUND OF LIFE BECAUSE YOU HAVE TIES TO WHAT IS PROBABLY THE LARGEST DISASTER EVER: THE EARTHQUAKE IN HAITI ...BECAUSE YOU ARE DOMINICAN, YOU ARE LIKE THE COUSIN WHO KNOWS MORE THAN EVERYONE ELSE ...YOU ARE FROM THAT ISLAND AND KNOW THE HISTORY, CULTURE AND STORIES. SO WE NEED YOUR INFORMATION AND INSIGHTS RIGHT NOW! PLEASE TEACH US.

Nicolás: Linda, I am still processing a disaster that made itself present to me in bits and pieces through the media, the telephone conversations that I have been having with my mother, Maragarita María, in the Dominican Republic, and email exchanges with Haitian friends in the U.S. and abroad. Unlike my stepfather in Santiago, who when the tremors hit, called his wife thinking that he was having a seizure, I have been shaken intermittently by the graphic images coming through computer and TV screens. I don’t have a BlackBerry.

Before I continue answering your question, I would like to mention that recently I had a long telephone conversation with Sandy Plácido, a young Dominican scholar from The Bronx. Haiti, of course, was at the very center of our dialogue. We asked each other whether this was the right moment to talk about it or to concentrate all our energies in helping this country. My replied to Sandy was “Why not do both things?” Why not use the momentum this nation is experiencing to ask questions we never dared to voice. Before hanging up, I brought up to her your idea to take on some of Haiti’s pain(s) through your DYSTONIA treatment. Can you expand on this? How does the transference of pain works for you and those on the other side? What are your thoughts behind this art-life action in the context of such a devastating catastrophe? Can I ask you one question I often get? WHY ARE YOU DOING THIS?

I am going to take up the cousin comment in your opening statement. Cousins are for me very close family members since for fifteen years I was an only child. Haiti was the cousin we never visited or the one whom, at any attempt to visit us, we would flee from. Nevertheless, this family member would stop by our places by way of defamatory stories circulating word of mouth in primary school about a black man from the other side of the island stealing Dominican children. Haiti was the boogie-man, el Cuco. Haiti was the cousin with whom I would have LOVED to played hide and seek in the dark Caribbean night. The cousin I was longing to meet. Haiti is the cousin that for two years has kept me an insomniac in the South Bronx. From 2008-2009 I received grants from Art Matters, the National Association of Latino Arts and Culture (NALAC) and Printed Matter to engage in Borderless, an art-life experience for which I have been traveling from my home in New York to Santiago de los Treinta Caballeros, my birthplace in the Dominican Republic, to trace any connection that my relatives and I might have with the neighboring Republic. Did I tell you that part of my mother’s side of the family came from Lebanon by ship? Some Lebanese families not related to us settled next door, in Haiti. Anyhow, I cannot yet discard the possibility of connecting with Haiti through a Middle Eastern relative.

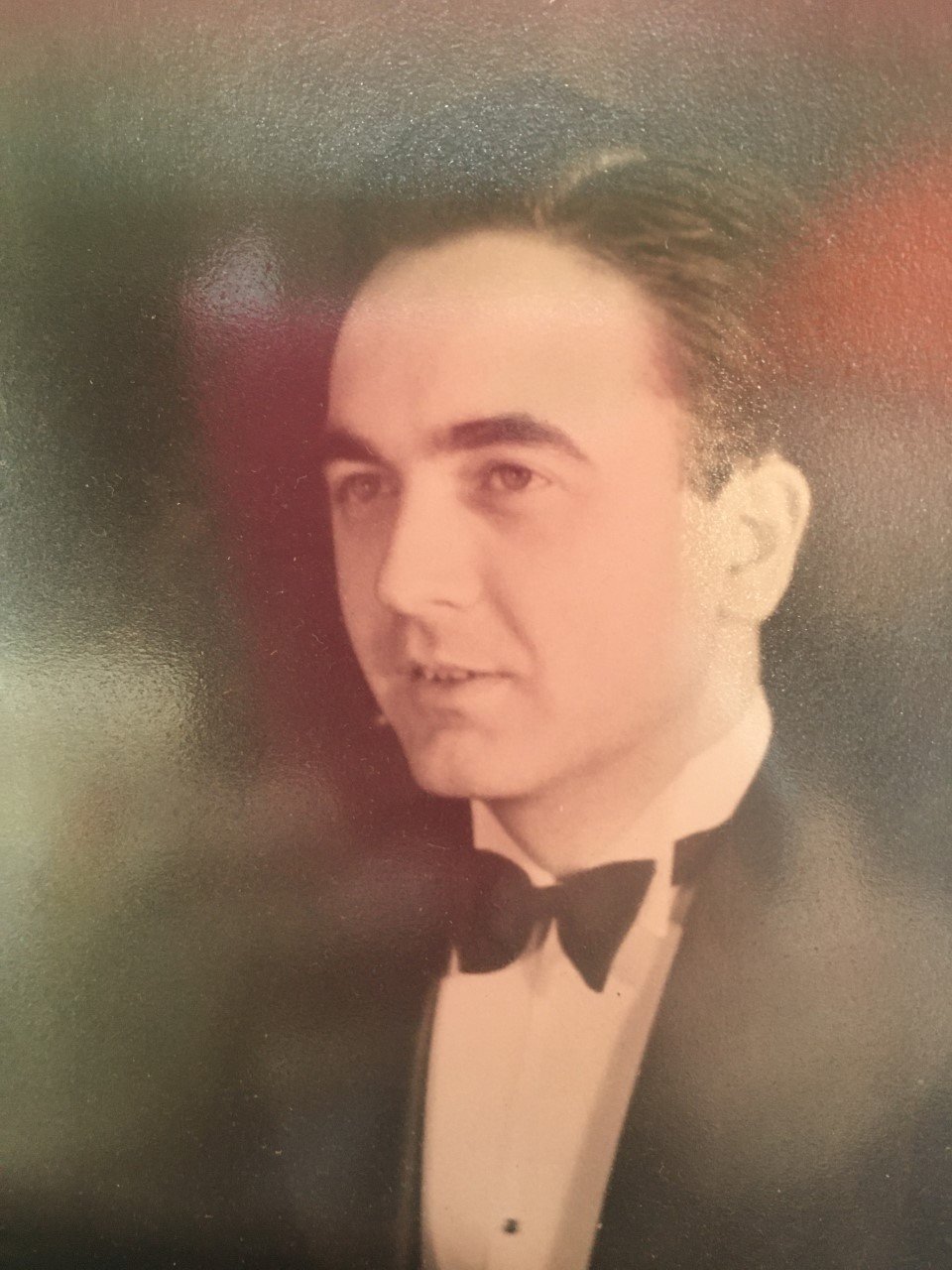

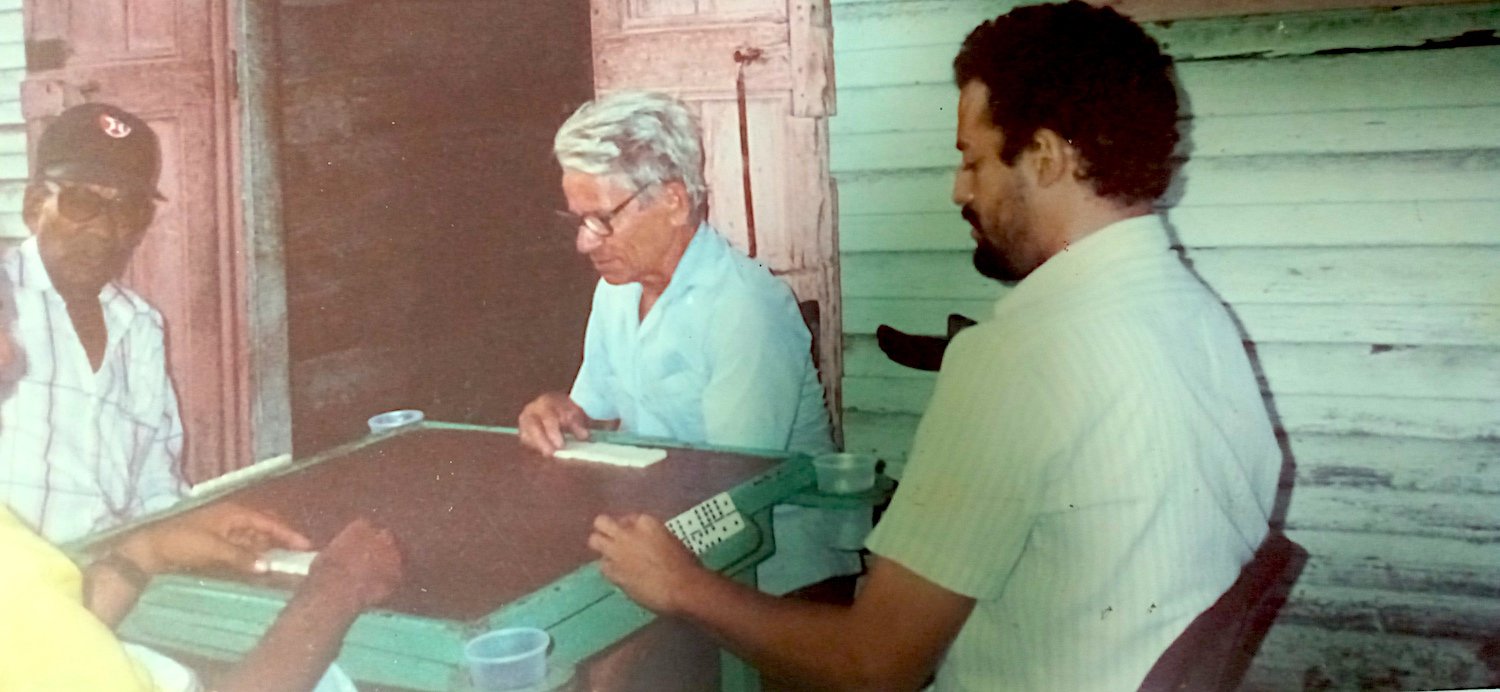

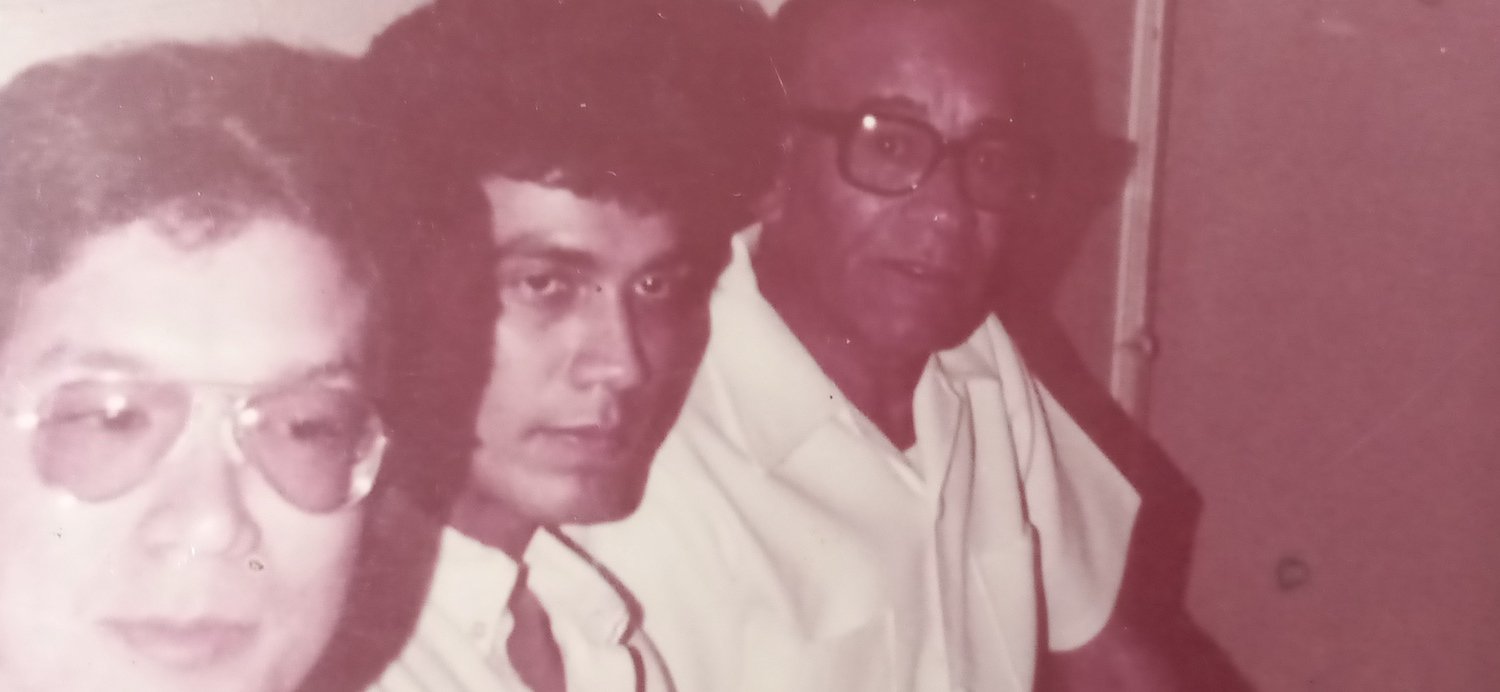

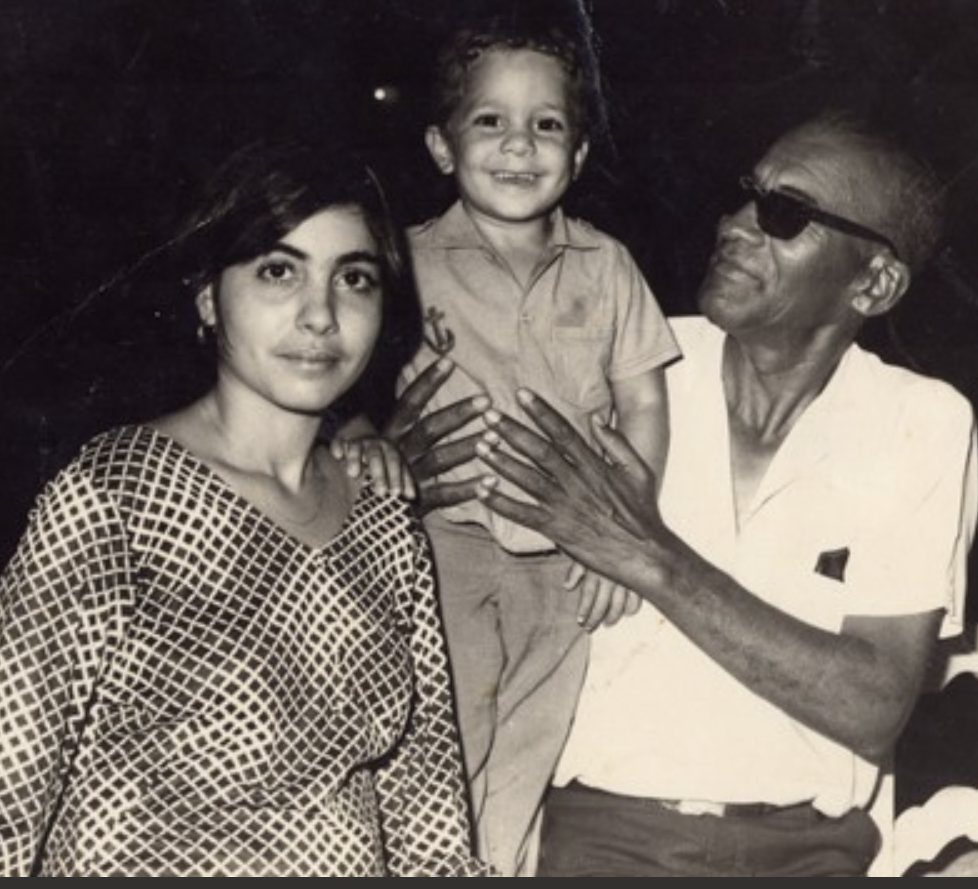

To summarize what could turn into an extensive narration, in 2009, in the town of Guayubín, near the Haitian border, Uncle Julio gave me confirmation of the Haitian background of my great-grandmother Inocencia Ortíz Belliard (Belliard was her French last name). Triggered by this revelation, I asked Uncle Julio and my cousin Venecia to take me to the local cemetery to find her grave. “She was black,” he said, un-self-consciously approaching the l stereotypical topic of race and ethnicity dominating almost all conversations about the relationship between the two countries. The same dialogue unveiled a link with Venezuela on behalf of my father’s side of the family. But let’s go back to Haiti. Inocencia’s grave is unmarked, and is next to that of her husband Manuel Espejo (Papá Muele). His is also unmarked, so we do not know for sure which is Inocencia’s. The two of them are resting side by side on what felt to my feet like a big sandbox dotted with conch shells in various states of disintegration. Why has it taken me forty-two years plus what seems like an endless journey through the cosmos to get to this particular moment? I don’t know if my late father Nicolás would have approved of this. His resting place is not too far from the locus of action. Papi shares a wide, white washed grave with his twin brother Eufemio. They are a few feet from Inocencia and Papá Muele.

Linda: WHAT DOES IT SIGNIFY, BEING DOMINICAN?

Nicolás: Rather than putting words in someone else’s mouth I am going to leave this question open for people to answer. What does it mean for you, reader to be Dominican? Please send your responses to this email

Is it dancing merengue, clinging to the tricolor flag, or eating an elastic mangú (man-goo) boiled and mashed green plantains that makes one Dominican? Have you have this dish? I could make it for you or we can have it at a restaurant in Longwood. We should have gone over this question while enjoying mangú with sautéed onions on top, melted cheese, and a glass of morir soñando, die dreaming, (orange juice mixed with milk). We can call it art-life. Any ideas for this? By the way, I don’t know how to play baseball. Does that make me less Dominican? I found this interesting video on youtube posted by a what seems like a young Dominican man living in New York City. It is worthwhile watching. Click HERE

In my case, Dominicanidad has meant undertaking an ongoing search of all of the elements that inform who I might be. I am Dominican because I am a: New Yorker, Bronxite, Lebanese-Dominican, Dominican-York, Lebanese, Catalan, Venezuelan, Haitian, African, New Berliner, Nuyorican, Spaniard, and who knows what else. I came to the realization that I am engaged in an undertaking that can bring my identity to some kind of dissolution or collapse. This process I am pointing to has brought me at times to an uncertain territory. I am up for this. Better there that than spending life in a prefab Lalaland.

Linda: BRIEFLY, WHAT IS THE CULTURAL HISTORY, THE POLITICAL HISTORY AND SPIRITUAL HISTORY OF BOTH THE DR AND HAITI...HOW DO THEY COMPARE AND CONTRAST?

Nicolás: What we know today as Haiti and the Dominican Republic was colonized upon Columbus’s arrival in 1492. The whole island was named Hispaniola, becoming part of the geographic portfolio of the Spanish crown. In less than a century after the conquest its indigenous inhabitants were decimated, and after years of colonial neglect, Buccaneers, a group of freebooters from different European places, settled on the island of Tortuga on the northwest coast. In 1667 France took possession of the west portion of Hispaniola. What follows is a long series of dispute between France and Spain for leadership over the colony and later on, Dominican and Haitian struggles to define the border demarcating both nations. The biggest national holiday in the Dominican Republic is the independence of the country not from Spain, but from Haiti in 1844. What is today the Dominican Republic was from 1822-44 Haitian territory.

It is worthwhile moving back in time. In the XVIII, as a result of dissimilar economies, African slaves and their descendants on each side of the island were engaged in a different kind relationship with their European masters. While French Saint Domingue’s expansion made Haiti the jewel of France in the Americas, the Spanish counterpart barely got by in an economy of subsistence. This resulted in a higher number of Africans arriving in Saint Domingue, and not only that, in a stricter demand for production. All of this will come to inform the overall identity of the Haitian and the Dominican Republics in regards to Africa and the colonizers. The stereotypical perception is of Haitians as poor and African and of Dominicans as lighter skinned Latin. The Spaniard Grandparent Syndrome (SGS), as I call it, is so prevalent in the Dominican Republic, where many claim to have a Spaniard ancestor. In any case, the first time I traveled to Spain I was taken aback by feeling at home. Was I not properly weaned from the motherland?

Pat Roberson talks about the pact Haitians made with the devil in order to obtain their independence from France and to form the first black republic in the Americas? The tele evangelist is not as historically uninformed as he seems to be at first, but ingeniously deceiving in masking the why of the many misfortunes of Haiti. The major one is the heavy reparations that France imposed on the newly created country (the equivalent today of 21 billion dollars) to recognize their independence and the U.S. later involvement in the country’s politics. What Pat is describing is the affront of a bunch of colored peoples to fight for their freedom. Historically, Pat is talking about the Bois Caïman ceremony on August 14th, 1791 were slaves gestated the revolution that would free them from the colonizer. The conflation of African beliefs was a unifying force in this event. Anyhow, Pat is not alone in his description of a nation who faithfully follows the wrong path, a crowd of glassy-eyed zombies walking after dark. The media has done a magnificent job painting Haiti as the poorest place in the whole hemisphere. Have we been told why? This link is to a video giving some answers to this question. It was sent to me by a Haitian colleague living in Berlin. Click HERE

One recurrent comment that I have been hearing in the midst of the catastrophe is that implying that something good might come out of this: What does a 7.0 earthquake mean in a place that before the earthquake hit was already a disaster? Wasn’t Haiti in a state of emergency prior to that?

A day or two after the earthquake, a reporter on TV got confused and said Haw… (meaning Hawaii), while trying to refer to Haiti. He quickly realized his mistake. It seemed like he swapped the names of heaven and hell during mass.

Can we I leave the discussion on spirituality for later? I know that you are about to ask me about one particular aspect of it.

Linda: WE ARE ALL VERY INTERESTED IN THE CONCEPT OF VOODOO AND HOW DO YOU WANT TO TALK ABOUT VOODOO AND HOW IT IS PRACTICED IN BOTH THE DR AND HAITI?

Nicolás: Voodoo, Vodou, we call it Vudú in Spanish, has had a good share of treatments in the U.S., from Hollywood movies to anthropological literature. From The Serpent and the Rainbow to Tell my Horse. To give you an example, in the section on Haiti in I Tell my Horse, Zora Neale Hurston narrates how she came face to face with a living dead, a Zombie, and goes on to describe some of the bloody secret societies that flourished in Haiti at the time of her research in the late ‘30s. In the Dominican oral history of zombification, people are taken from the East to the West side of the island to be turned into one of these creatures. There are those who affirm having seeing someone who disappeared in the Dominican Republic walk the streets of a Haitian town.

Growing up it was commonplace for many of my family members and neighbors in the Dominican Republic to practice ritualistic actions for the purpose of changing the course of an everyday situation: an upside down broom with several crystal of sea salt, propped on a corner helped an overwhelmed host get rid of an undesirable guest. I tried this on many occasions. Women stuffed in their shoes a piece of paper bearing the name of the man they wished to keep subjugated and under the soles of their feet. The names of undesirable people were frozen at the subzero temperatures of the electric refrigerator. To me this was a mild form of zombification. We used camphor to shoo away evil and were instructed to pick up suspicious packages with our left hand. I remember helping my grandmother tie Saint Peter’s testicles, symbolized by a stone, which we hung to stop a torrential rain.

Chromolithographies of saints were put upside down until the saint fulfilled one’s request. Saint Anthony has spent a lifetime with his head on the Dominican soil. Wannabe brides do so to urge him to find them a suitable candidate for marriage. Some of the ritualistic actions that I described above could possibly trace their origins to our African heritages, others are the product of the religious syncretism that prevails in an area where Africans forcefully brought to the region worshiped some of their deities through the representation of Catholic imagery. For example, Changó, the god of thunder is represented by the image of St. Barbara and Belié Belcán’s Catholic equivalent is as Saint Michael Archangel.

Linda: WHAT DOES VOODOO MEAN TO YOU PERSONALLY NOW? BACK WHEN YOU LIVED THERE?

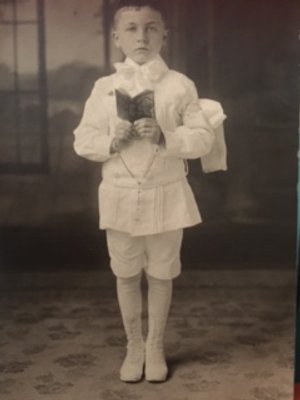

Nicolás: Linda, How does one deal with Catholic guilt? How does one reconcile with believes other than those instilled through centuries by the Church? Is it fair to answer a question with another question? Please give us a recipe for shedding off our Judeo-Christian guilt. We are the children of the children of the children of the children of the children of the children of the children who were brought here from Africa. We managed to hold onto a piece of the umbilical cord. Mine was sandwiched in a photo album. I was born with forceps, went to church every once in a while. The Catholicism we practiced at home was a lapsed one. I will try to keep our conversation on Vodou as simple as possible. We are treading into a complex territory. The reference to horses has to do with the fact that when the Vodou practitioner is possessed by one of the misterios or luas (spirits) they are said to be mounted by them. The lua or misterio rides the person hosting them. So much to tell. My mother would take me to the houses of people who had the most amazing altars. We would go there for consultation and to get help fixing certain aspects of our lives. There were those who would go to them to get trabajos, works for getting married or for enhancing their luck. Our visits were mostly for spiritual purposes. I was told over and over that I had a light and that I was eventually supposed to get baptized in order to serve the spirits. By the age of seven or so I had amassed a personal altar of a remarkable size. I would use all of the money that Lebanese relatives would give when I would go to visit them at their textile stores downtown to buy chromolithographies of Catholic Saints. The 4” x 6” were no more than a quarter. One of my favorite ones was St. Clare holding a monstrance in her hands. Clare, Clara (clear) in Spanish. Her role was to clear up our path from obstacles.

Now. I keep in touch with one Vodou practitioner. We became good friends when I was attending a master degree at Tyler School of Art. He helped me with my thesis on the aesthetics of the Dominican Vodou altar. This man and his friends taught me a great deal about sharing and caring for one another. Together we would travel to the most economically disadvantaged areas of Santiago and would be received by those who had so little with such amount of generosity. Now I do not practice Vodou but recognize that I have been deeply shaped by it. I often think of the light that I carry inside of me. I ponder about the implications of awakening it.

The Spanish speaking Caribbean has a very strong relationship with the flesh, with the here and the now. I have call it a culture of the flesh. Vodou is a religion in which the deities can travel to our physical world and manifest themselves tangibly. For example, I was able to interact with El Barón del Cementerio, St. Elijah or the Lord of the Cemetery, during a celebration. The woman possessed by him wore a purple and black gown. She resembled a dead person. Here we are talking about gender bending. Linda, I warned you before of the complexity of the subject. I am just scratching the surface.

Linda: HOW DOES IT INTESECT YOUR ART/LIFE? ARE YOU COMFORTABLE WITH IT? IT IS MYSTERIOUS AND VERY COMPELLING TO OUTSIDERS AND SO WE ARE ALL CURIOUS. AND FRIGHTENED BECAUSE IT IS SEEN AS TABOO. THE TABOO MAKES US INTERESTED AND ALSO FRIGHTENS US...

Not too long ago I realized that almost everything I create references altar-building in the Vodou tradition. When I moved to the South Bronx, five years ago, I vowed to myself to keep my office free of art, objects, or any kind of decoration. You should come and see the place: braids in glass jars, a calendar of the Sacred Heart of Mary and two of Fefita La Grande (a folk singer in the Dominican Republic who is in reality a performance artist who happens to play the accordion), a huge French Canadian print of a nurse tending to sick man, who is in reality Jesus, a holy Rosary in a plastic bag, a purse of yours that I got at one of your performances, soil from the Dominican Republic and Haiti side by side in jars, like the two portions of the island, like the graves of my father and his twin brother, like the unmarked tombs of my great grandparents near the border, like the Vodou Marasas: St. Cosme and St. Damian.

There is fear in what we don’t know. I fear to drive on an US highway. I fear the prospect of wearing a suit and tie and working on Wall Street. I used to fear leaving New York City for more than a day. There is fear in treading into the unfamiliar and getting swallowed by it. I used to fear becoming an “American” until I realized that I was one before I moved to the U.S. from the Americas. Why do you think that outsiders including yourself are scared by Vodou? Can you suggest a performance for dealing with fear?

Linda: HOW WILL THE EVENTS IN HAITI AFFECT YOUR ART AND LIFE? WILL IT CHANGE THEM FOREVER?

Nicolás: Any security we have put in place to make our lives safer can slip away in a matter of seconds. We should not wait for a tragedy to come in contact with those we care for. I open my eyes and everything is standing. I close my eyes. I open them again and I find myself in the midst of the rubble. Earthquakes are constantly trying to wake us up. Some of these tremors can only be experienced at an individual level, but nevertheless hit all of those around us. Paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, videos, installations, audio pieces, site-specific works, get lost during periods of wars, massacres, nuclear destruction, genocides, ethnic cleansing. Yet art remains forever as reminder of its power to pull us out of the muck. I mean art as: helping others in distress, transporting a sick person to an emergency room, emptying our pockets and sending money to those in need.

Days after the earthquake my cousin emailed me from Hong Kong to ask me how will this situation change Borderless. I think she really meant to ask me how is this going to affect my search. I am sure that many of our Haitian cousins lost their lives to the tragedy. I am sure that many more remain to be helped and rescued from the debris, and that many, many, more than those dead have survived and will be there for our first encounter.

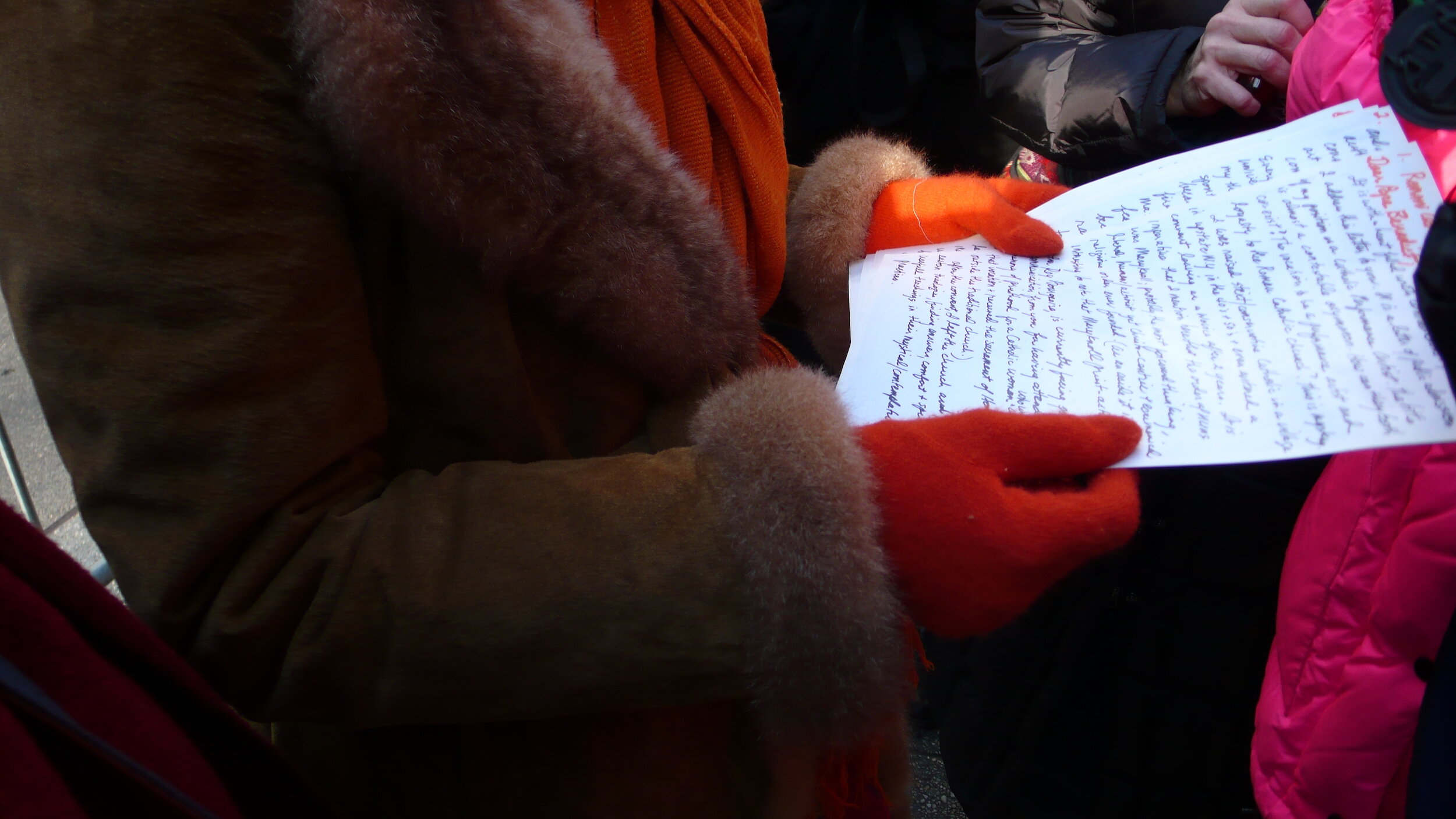

On January 25th I received an email from Notreda Belliard sent from the border town of Ounaminthe, telling me in broken Spanish that she was OK: Estoy contento de tomar tu noticia. Espero que todo va bien para tí. Para nosotros no hay nunguna persona que se muerte durante este terremodo. Y tú como estas?” I am happy to hear from you. I hope that all is well. There are no dead among us. And how are you?

Notreda and I met during my visit to Haiti in 2009. She promised to introduce me in future visits to other members of the Belliard family.

Dear Reader I am looking to get in touch with the Belliard family in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. My e-mail addresses is: click HERE

Linda: ASK YOURSELF ANY QUESTIONS I MISSED.

Nicolás: Thank you, Linda.

What can I do to help Haiti’s current situation?

Donate Now. Please don’t wait.

Pray.

Get involved.

Adopt a child who might need a home.

Research the history of the place.

Update our own image of this country.

Give a presentation on the colonization of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Question the leaders of the powerful nations and their involvement in other countries.

If living in the so-called First World: Avoid repeating historical mistakes.

If in the Dominican Republic or in Haiti: Strive to live in harmony.

Write about Haiti in your church, office, school or college newsletter.

Become a Haitian.

MONTANO'S COMMENTS: NICOLÁS AFTER READING AND THINKING ABOUT WHAT YOU ARE THINKING ABOUT, I AM THINKING THESE CONSIDERATIONS:

1. DO YOU THINK THAT YOU HAVE A LIFE'S WORK/ART SORTING OUT YOUR AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

2. DO YOU FEEL THAT YOUR LIFE AS A PERFORMANCE ARTIST CAN BE "USED" TO MAKE A NEW UNDERSTANDING, A NEW PEACE, A NEW OPENING OF TOLERANCE BETWEEN THE D.R. AND H.?

3. WE TALKED ABOUT THE PERFORMANCE OF MY BEING OTHERS (BOB DYLAN, MOTHER TERESA, PAUL MCMAHON AND FICTIONAL OTHERS INCLUDING THE ALCOHOLIC, FRENCH WOMAN, COUNTRY WESTERN SINGER). DO YOU FEEL THAT IN D.R. - H WITH THE PERFORMANCE PRACTICE THAT YOU ARE DOING IS TIME FOR YOU TO BE EVEN MORE PERFORMATIVELY "HAITIAN" THAN YOU ARE ...THAT IS THE BRAIDS ARE "HAITIAN" CORRECT? I AM NOT PROPOSING YOU DO "BLACK-FACE" BUT I WOULD DEFINITELY TALK TO ADRIAN PIPER NOW ABOUT YOUR CURRENT PRACTICE...

4.HOW DO YOU TEACH TOLERANCE AND RESPECT TO THE CHILDREN OF EACH CULTURE, D.R.-H.? CHILDRENS BOOKS? WORKSHOPS? LECTURES?

WHY? IF I WAS BROUGHT UP IN THE D.R. AND WAS FED THE THOUGHTS YOU WERE FED ABOUT H. , I WOULD THINK THAT IT IS TIME FOR A RE-THINKING OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE TWO CULTURES. AS A PERFORMANCE ARTIST AND A D.R , YOU ARE IN A VERY WONDERFUL POSITION OF BEING ABLE TO INTERVENE HERE, HELP TRANSFORM SOME OLD WOUNDS.

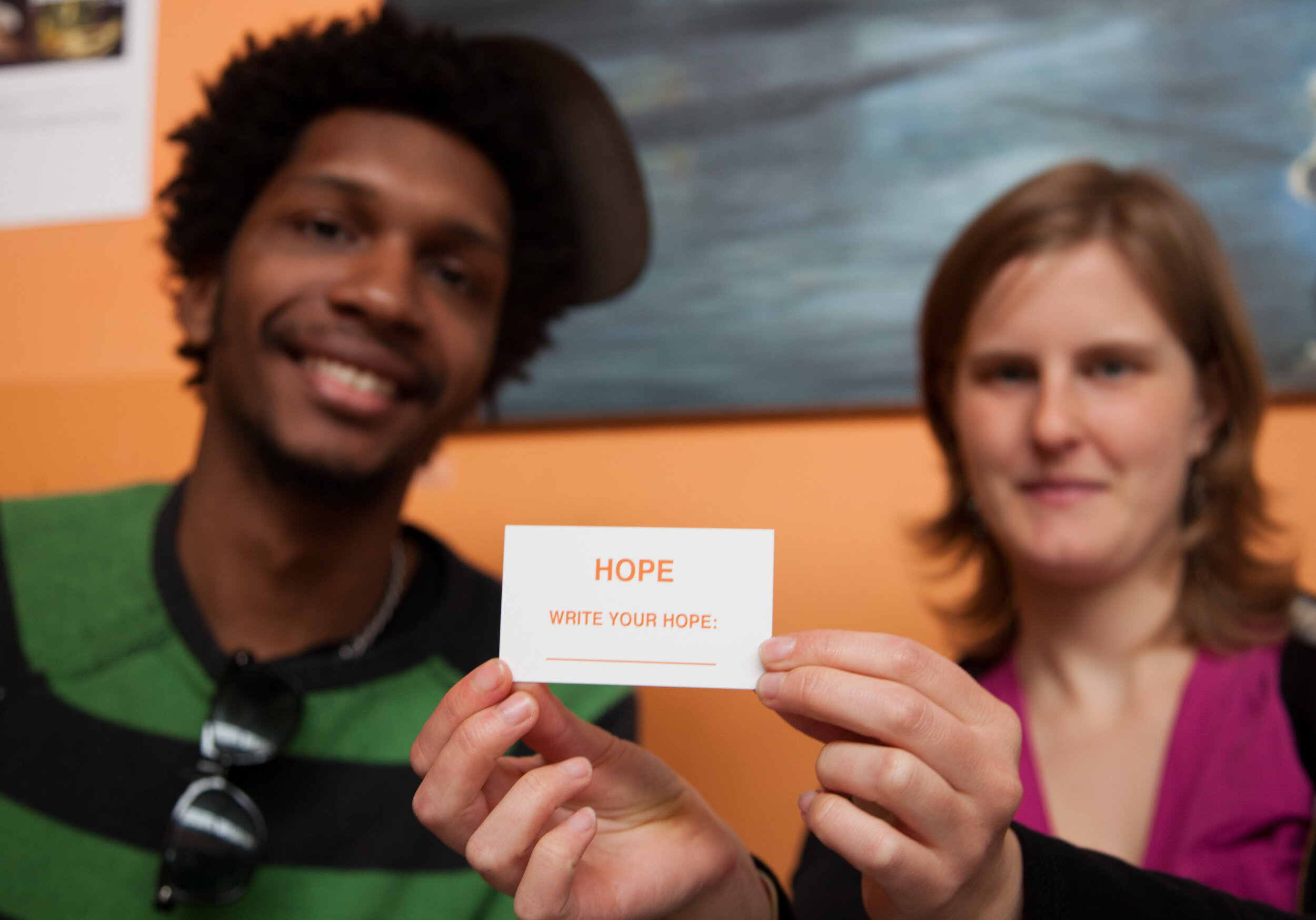

I SEND THESE AS COMMENTS , NOT AS QUESTIONS TO BE ANSWERED. AGAIN, N, THANKS FOR TEACHING ME AND GIVING ME HOPE THAT ART CAN MAKE A BIG DIFFERENCE IN OUR OWN LIVES AND IN THE LIVES OF OTHERS. IN ART/LIFE/LAUGHTER, LINDA MARY MONTANO

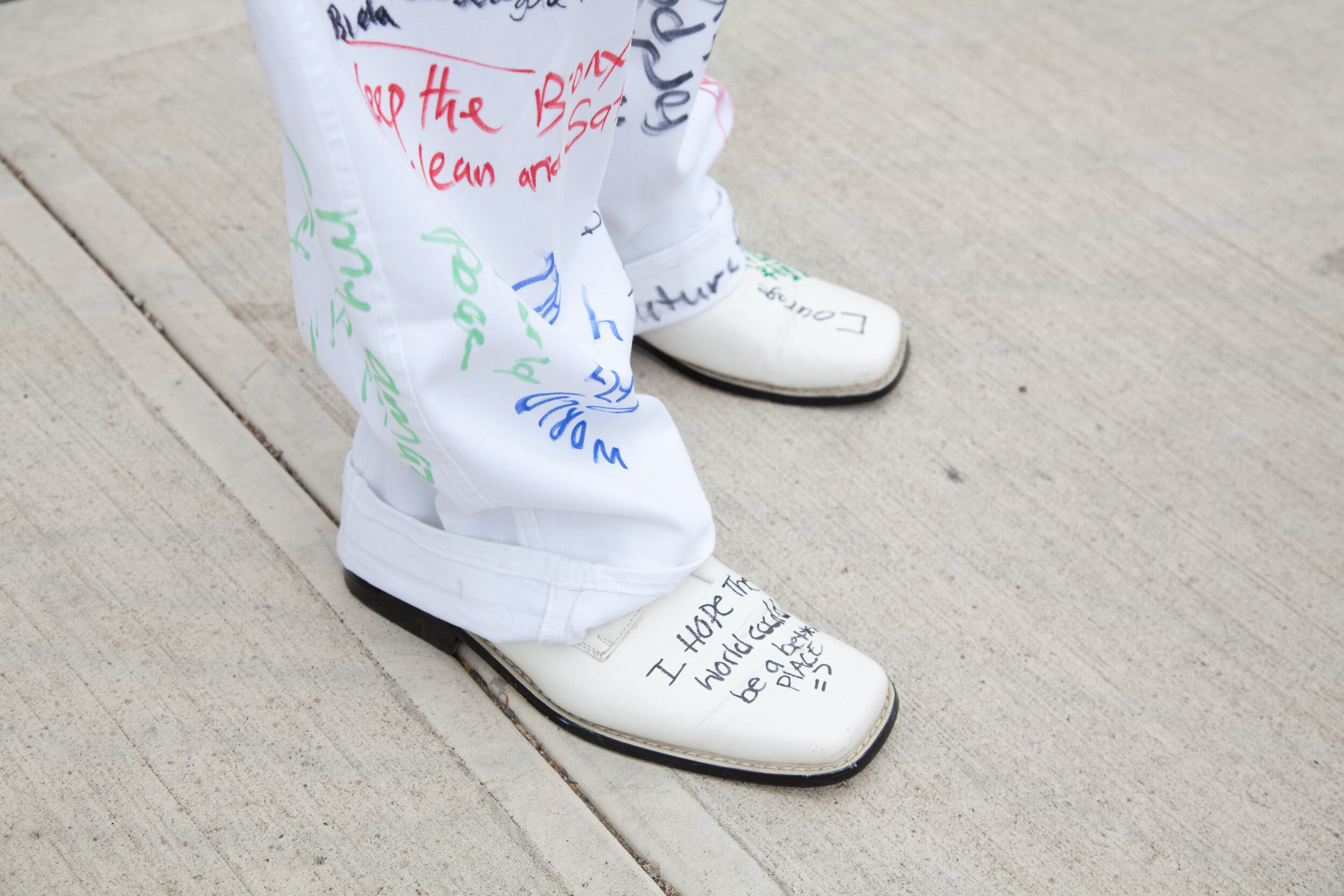

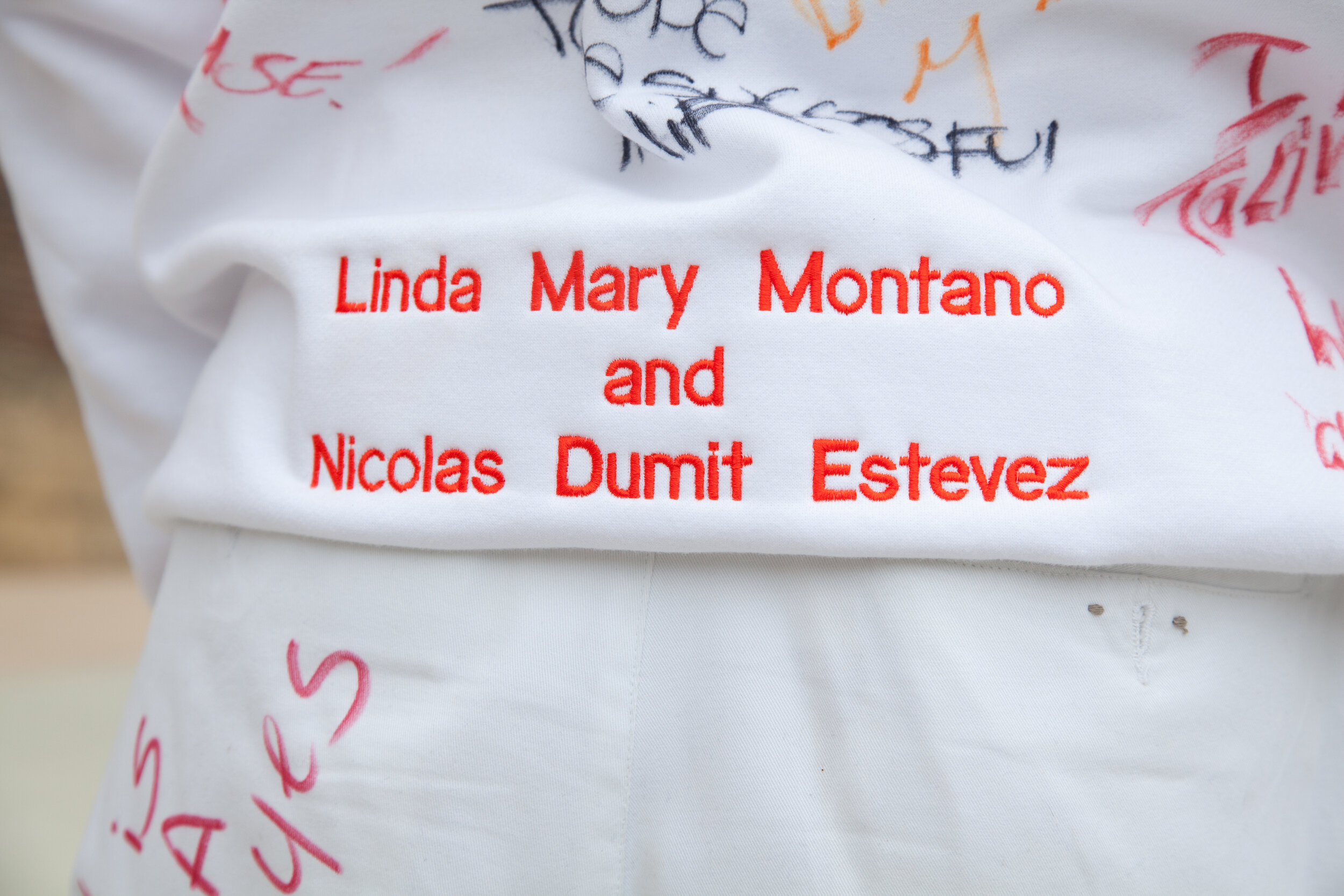

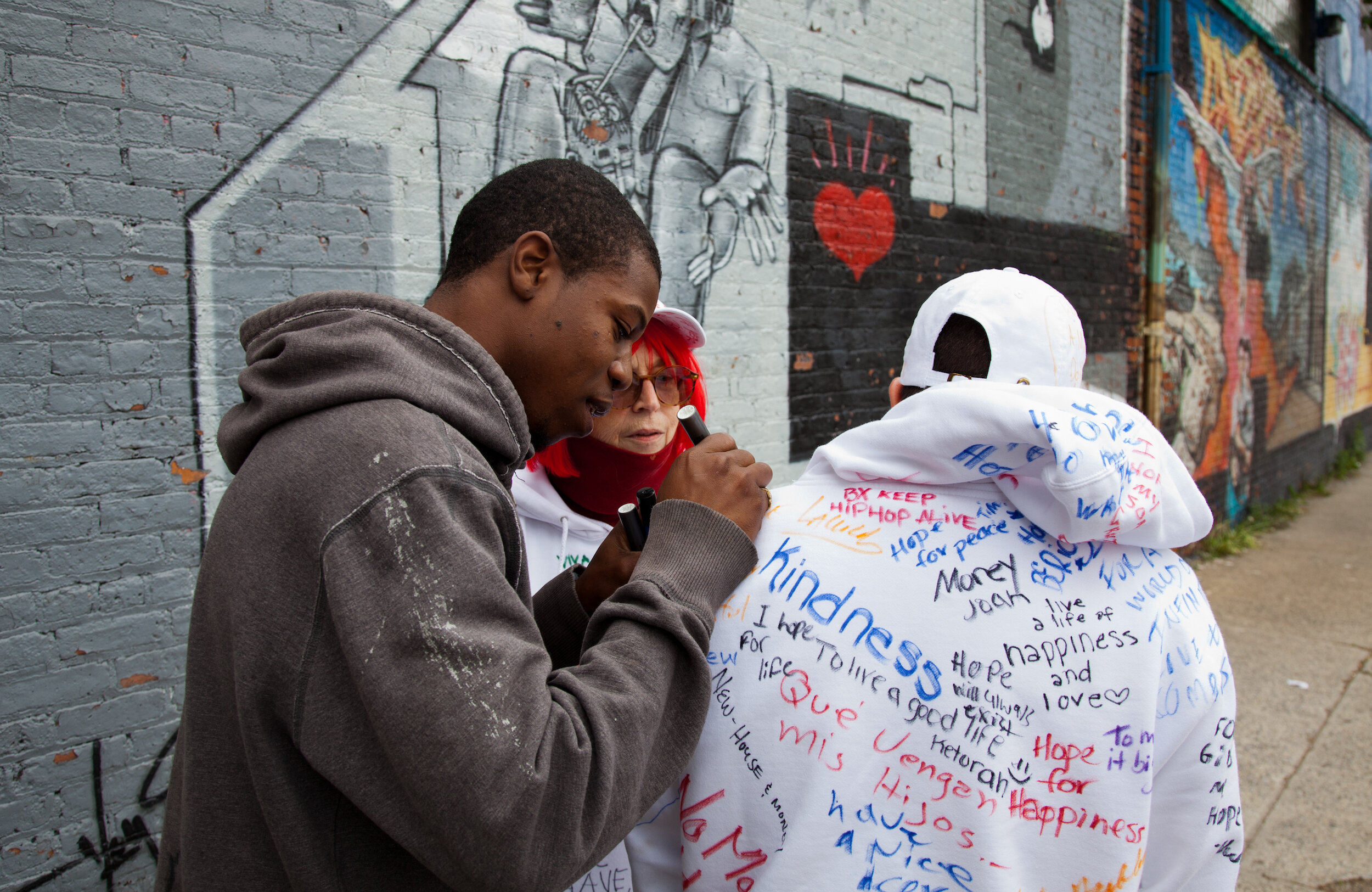

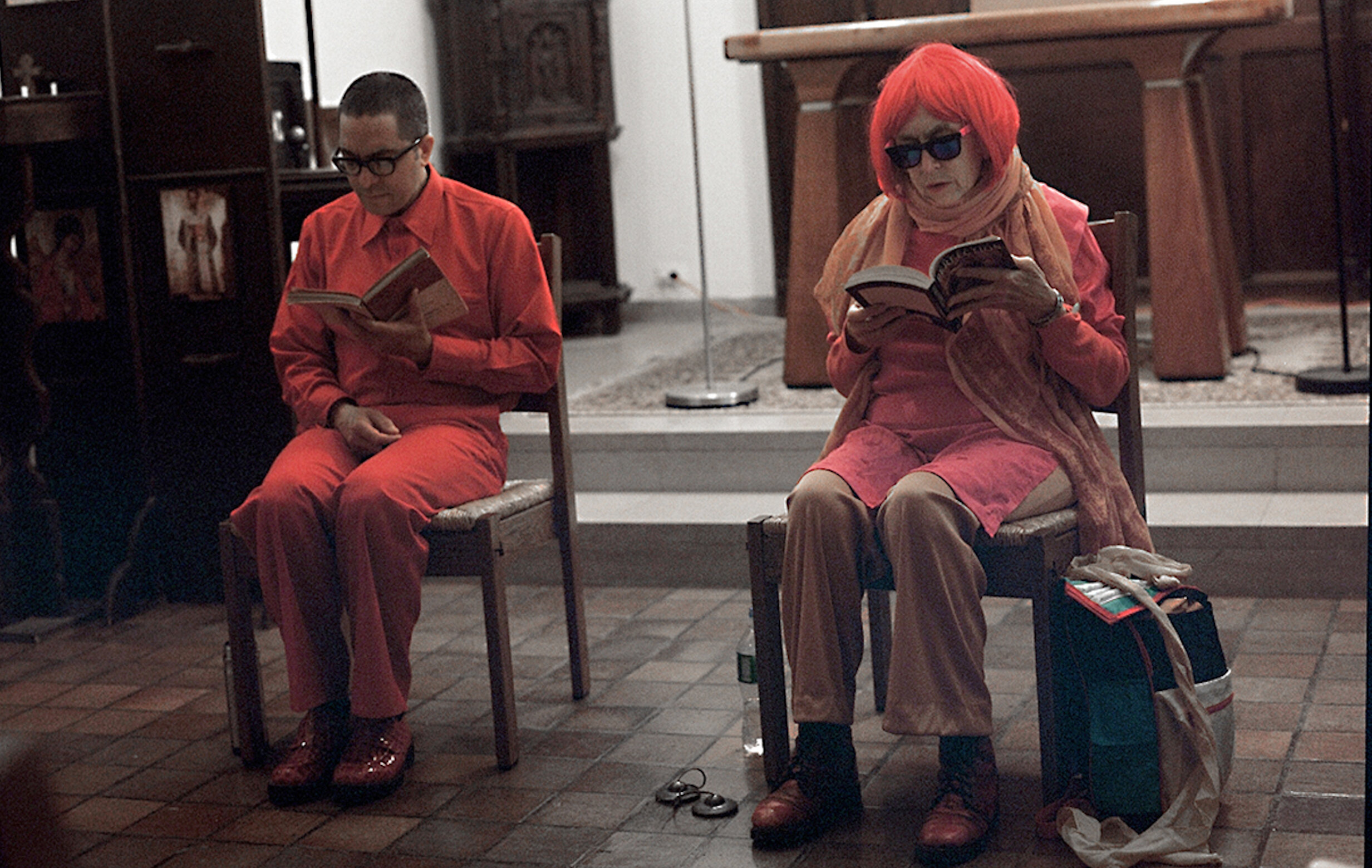

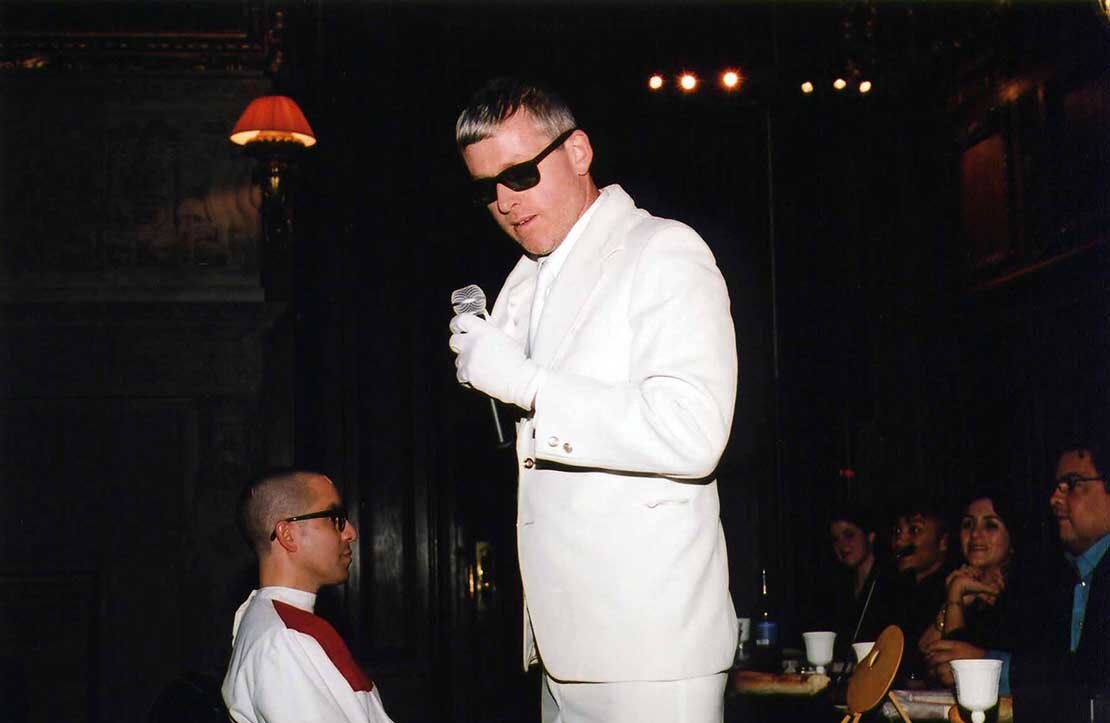

Nicolás: Dear Linda, I just saw your comments at the end of the interview. I kept looking for them within the main text. I would like to think about your words for several days, since there are very relevant to the path that I am seeking to take with art-life. I don't know if I mentioned to you that before I emailed you for the first time in 2006, from Saratoga Springs, I kept hearing a voice telling me: "get in touch with her, get in touch with her". I am glad that I did. God bless you. I am including some images of my trip to the cemetery in the Dominican Republic Taken by Sol Aramendi. Unlike in the U.S., some of the cemeteries there are quite active with people bringing food to the Lord of the Cemetery, people performing Vodou, people praying, talking to the dead or enacting rituals. Most cemeteries are gated and close around 6 PM. Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles Ortíz Morel Belliard