Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles Morel: Aurora, you were part of the Research Fellowship that Alex Campos so generously organized at Hispanic Society in New York. Our connection to Alex goes back to the Center for Book Arts, also in New York City, when he made possible so many interesting initiatives at this organization. What did you do research-wise at Hispanic Society and how does this relate to your bookmaking practice at large

Aurora De Armendi Sobrino: Nicolás, thank you for inviting me to The Interior Beauty Salón to be in conversation with you. I met Alex Campos at the Center for Book Arts, NYC in 2011. CBA was the first institution that supported my work right after graduate school when I was awarded a one-year fellowship to continue my studies in book arts. Artist Sarah Nicholls ran the studio programs at CBA at the time and was also supportive of my application and work as well. The Center for Book Arts is an institution I hold very dear in my heart and, like you said, Alex and staff members made possible many projects that wouldn’t otherwise have been brought to light and experienced by the larger public.

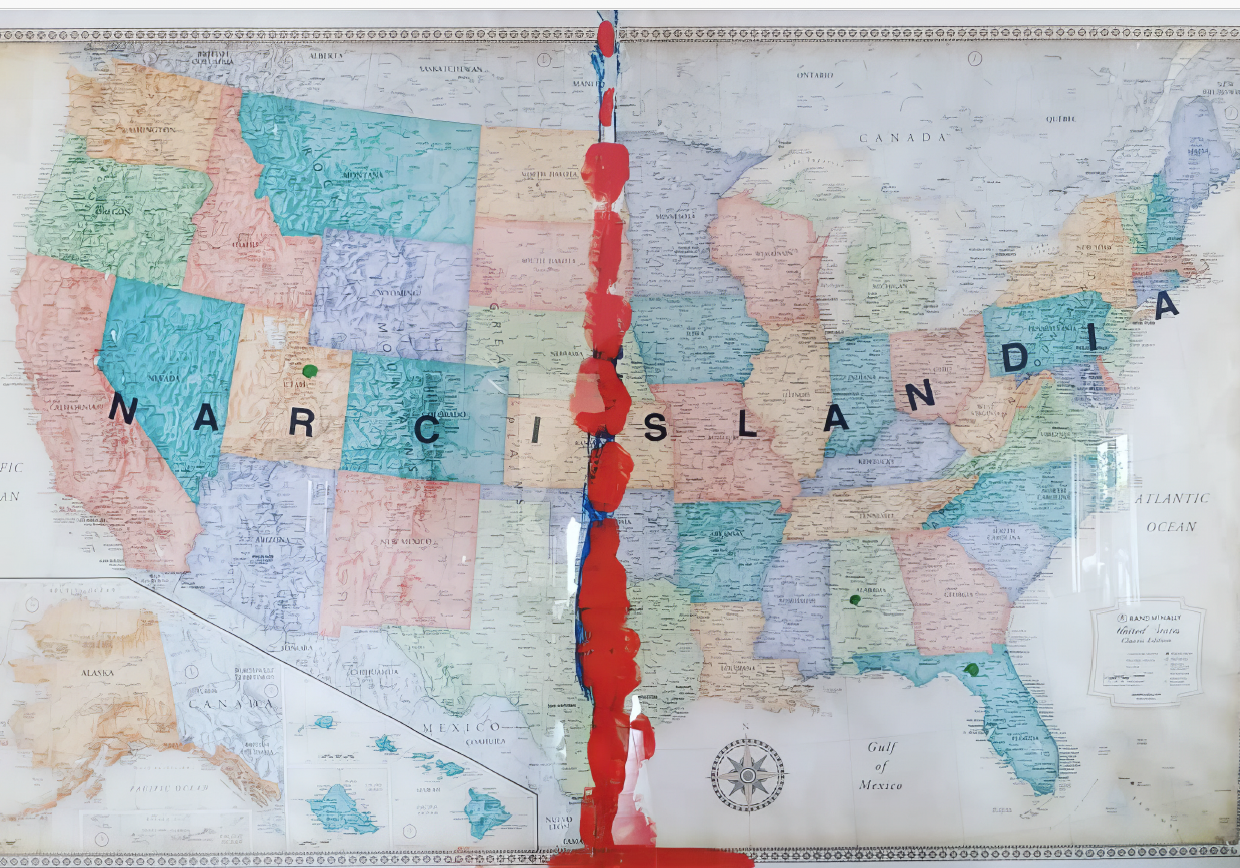

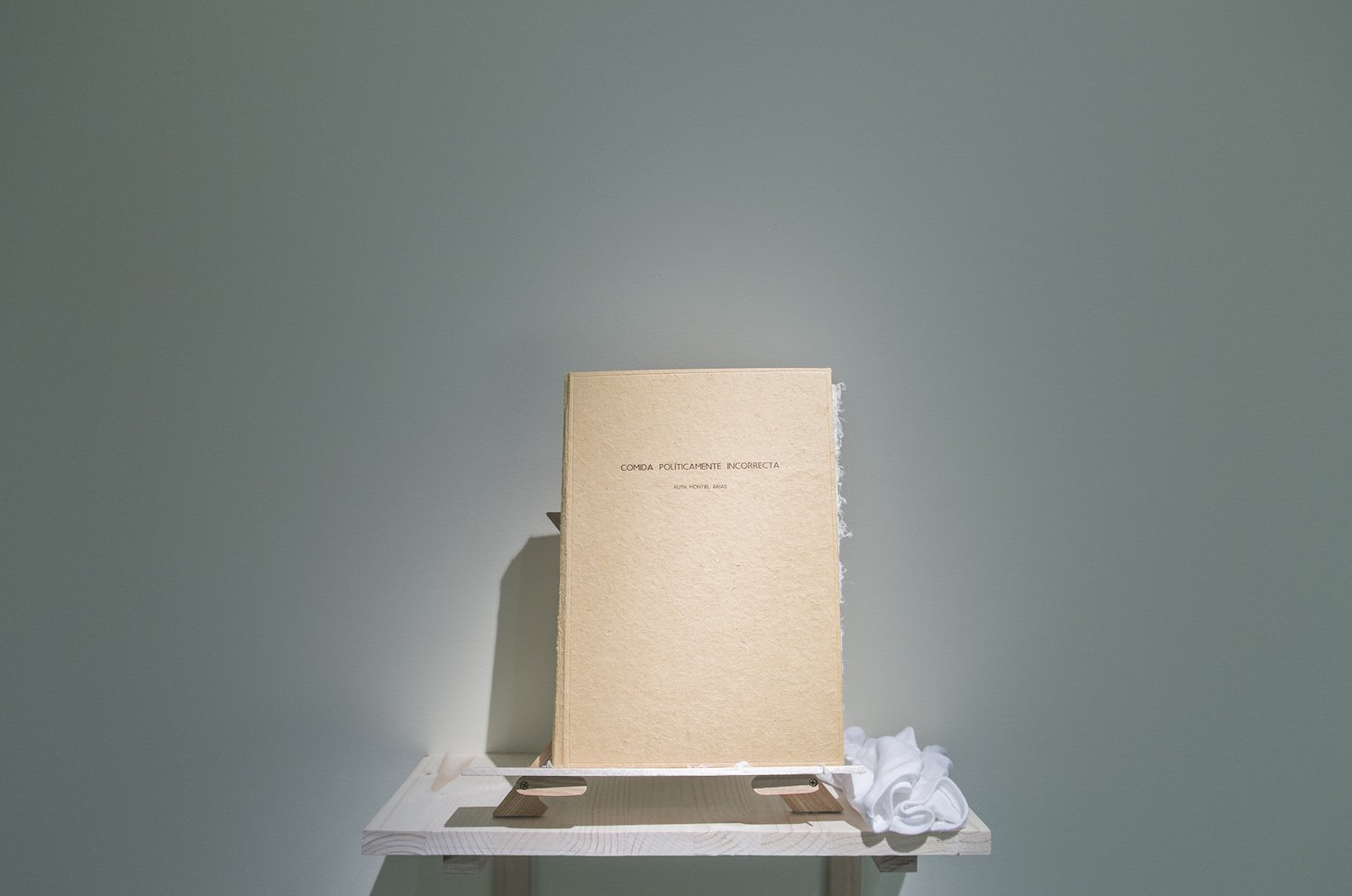

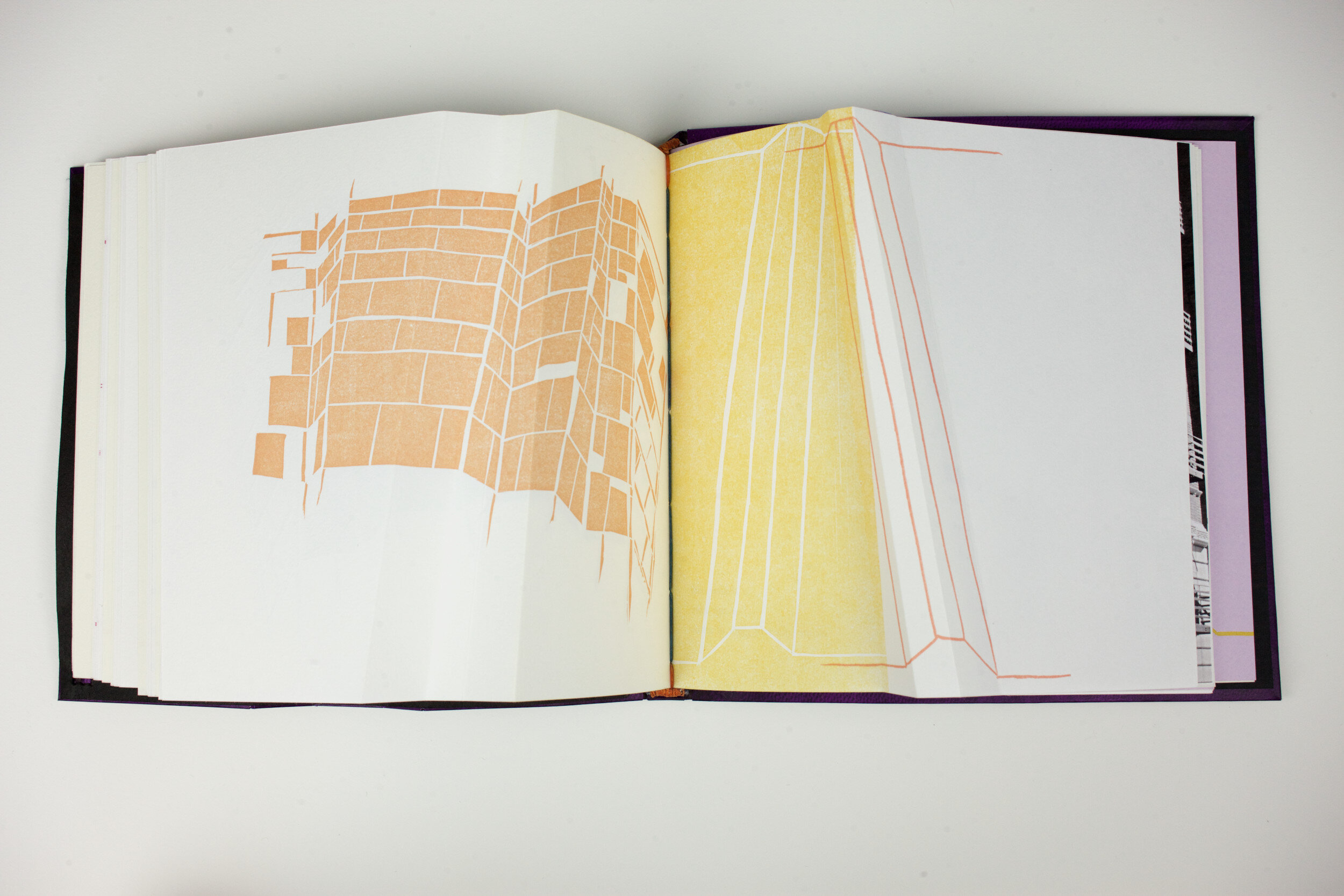

When Alex Campos invited me to participate in the Research Fellowship at the Hispanic Society, I took the opportunity to explore their collection and view maps of the Americas, manuscripts, Derroteros (briefly define, parenthetically, for those who don’t know this term) and documents from the 11th century until the present, studying different bindings and their uses in different contexts, most of them from a colonial perspective. Vanessa Pintado, Assistant Curator of Manuscripts and Rare Books at the Hispanic Society was instrumental in recommending manuscripts to study. For example, one of the Derroteros I viewed incorporated flexible, lightweight, hemp hand woven cloth covers, which allowed, through greater portability, marineros to write notes and make drawings of the lands they were mapping as they were traveling by boat.

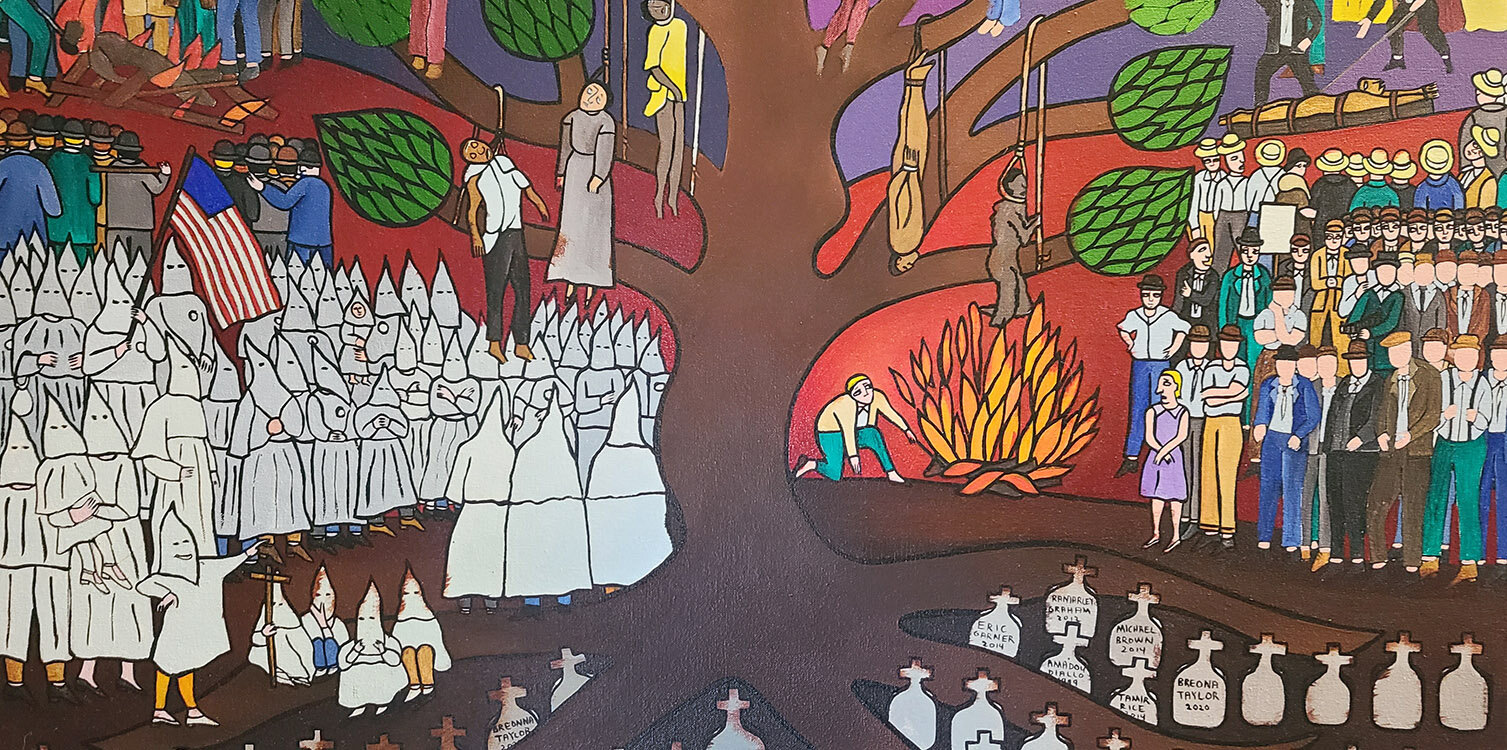

One of the manuscripts I studied, Codex Kaska, Títulos de la propriedad raiz del pueblo de Tizayuca made in the year 1536, illustrates Tizayuca as a territory in Mexico with Aztec art using Nahuatl language. The manuscript is painted with hand-made pigments on Maguey paper. I found this work fascinating as the artist chose to depict the agave and maguey plants, as well as the mountains and bodies of water larger than the colonial settlements and churches. The hard-cover leather binding was added later, completely unrelated to the content of the manuscript. I’m assuming the binding decision was made to preserve its content. Studying these manuscripts and maps gave me a deeper insight into the violence of colonization. The maps showed the erasure of native languages and the objectification and commodification of nature including flora, fauna and humans.

NDEREOM: I am fascinated by books of all kinds. I am one of those people who reads almost anything and everything that lands in my hands. I do this as a way of gaining understanding of as many perspectives as possible in a world that is so allured by echo chambers and where having a debate or a good fight is becoming more and more rare. The books I read include from heavy duty theory—which a friend suggested I do not read before bedtime—to comics, and I just got a used book which compiles advice from a newspaper column written by Sugar, Cheryl Strayed. To this I will add that the thinking is that I am going to find in the next book I purchase or come across the words of wisdom that will save my life, and so my home has become a library! How did your love for bookmaking start? What was the impetus for you to become a bookmaker? Aren’t all of us writing the book of our own lives on a daily basis, metaphorically speaking?

ADAS: I smile as I read your question, Nicolás, overcome with this feeling of warmth towards books and learning. I need to check out the newspaper column written by Sugar! … I can begin by saying that I grew up in a home where books were always present. My home in Puntabrava, Cuba where I lived until I was 14 years old was a modest house my paternal grandparents designed and built with hard work. The house had a very small study room. The study room had a large desk in the center, a typewriter, a file cabinet and shelves with books next to the walls. My dad, Angel Alberto de Armendi y de la Portilla kept his medical books in the study room and my lovely uncle Rafael Ángel Juan de Armendi y de la Portilla, who passed away this year (1941–2025), had poetry books, including the complete works by José Martí (books that had belonged to the family for a long time), books by Felix Varela and many other writers. There were also notebooks with cooking recipes, music lessons and art history books which belonged to my paternal grandmother, María Aurora Gregoria de la Portilla y García (1901–1986). I remember being as tall as the desk and wandering in the study room, opening the glass doors of the bookshelves and browsing through the books, especially books with photographs of diseases, the human body and art. I lingered in the pictures.

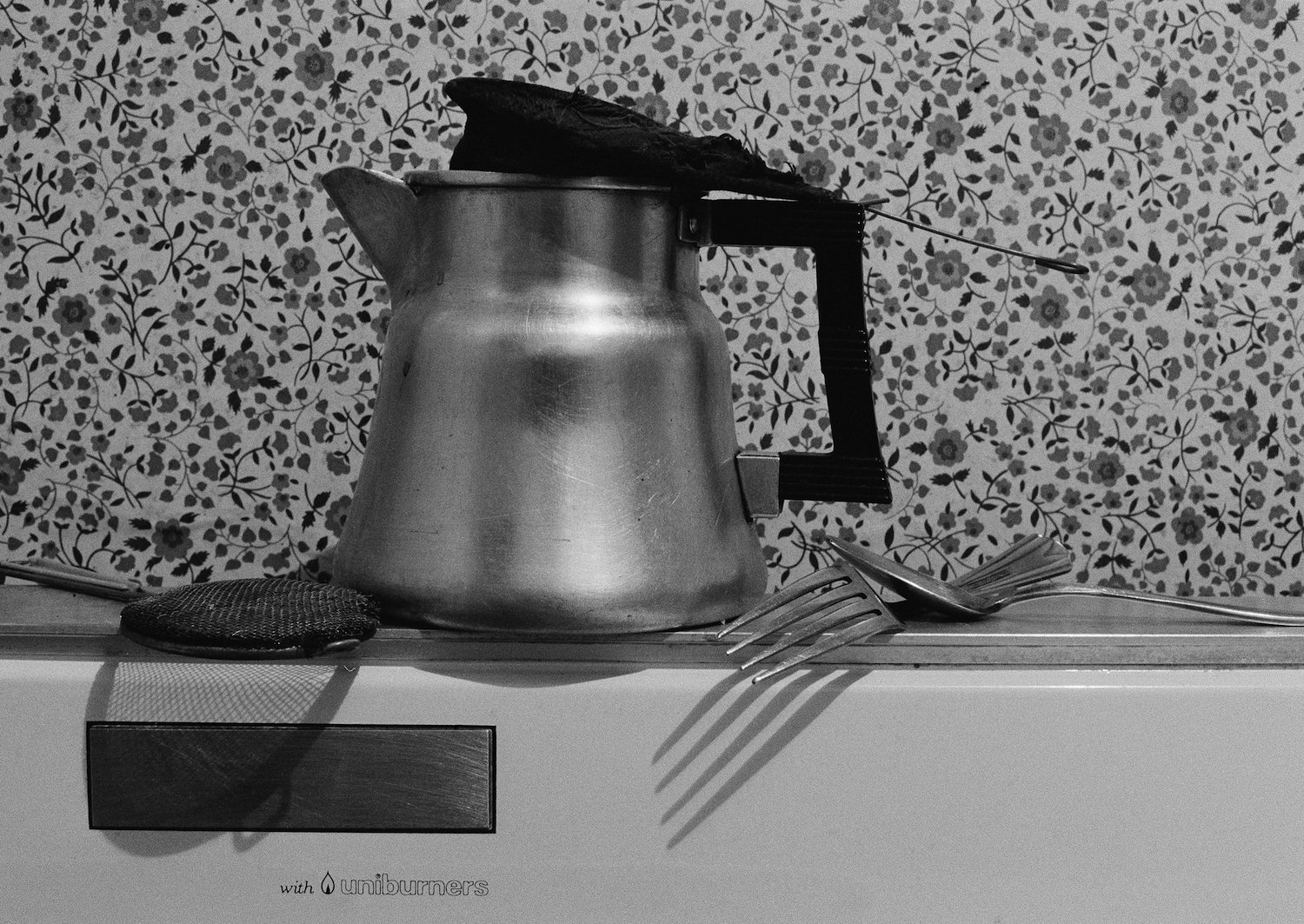

I was born in 1981 and by the late 1980s, materials were very scarce in Cuba as we were entering the “Special Period” in Cuban history. I remember making my notebooks with recycled brown paper and drawing lines across the page with a ruler and a pencil so I could write my school notes. When the school textbooks were given to us each year, my mom Marta Sobrino taught me how to make covers for them using recycled paper. We would do this activity together every year. I remember loving paper since an early age, las cuquitas cubanas were my childhood dolls (all made from paper) and in every birthday party my mom will make colorful cadenetas made with recycled paper strips and wheat paste. My first artist book, without knowing I was making one, was when I began collecting and arranging collages of used, American candy wrappers, a scarce material I’d occasionally find in the trash in Cuba. The act of making compositions of candy wrappers and playing with their colors and typography using paper clips was very special to me. In 1996, my family arrived in Miami after a 10-month refugee detention in Guantánamo Bay; in Miami I visited an American supermarket for the first time and realized there was nothing special about my collection of candy wrappers other than I had made creations with them…there were hundreds, thousands of packages shelved in stores for quick consumption and disposal. I felt so overwhelmed by the excess of objects in this country.

I always read in Spanish and more so when learning English during my high school years in Miami. My actual understanding of the technical aspects of making books by hand, their materiality and their relationship between form and content began at The Cooper Union School of Art where I took my first artist book class with photographer and author Margaret Morton (1948 – 2020) and made paper by hand with artist and designer Cara Di Edwardo. My education on the craft of making books and papermaking expanded at The University of Iowa, learning from Julie Leonard, Timothy Barrett and Emily Martin among other teachers... and later at the Center for Book Arts in NYC during an artist fellowship where I deepened my understanding of the artist book by working and learning from Ana Paula Cordeiro, Sarah Nicholls, Roni Gross and colleagues Susan Mills and Biruta Auna, and many other teachers. I don’t think of myself as solely a bookmaker, when I work in the book format, it is because the project requires an intimate reading. I love the time-based nature of books; how portable they are, facilitating reading in any context.

Aren’t all of us writing the book of our own lives daily, metaphorically speaking?

Our bodies carry our ancestral genetic information, and everything we experience. I think of my body as my sacred companion, the one who allows me to experience the world as I know it. It brings me to this quote by Clarissa Pinkola Estés, “The body remembers, the bones remember, the joints remember, even the little finger remembers. Memory is lodged in pictures and feelings in the cells themselves. Like a sponge filled with water, anywhere the flesh is pressed, wrung, even toughed lightly, a memory may flow out in a stream.”

Nicolás, you have made of your home a library…and Borges said, “he imagined that Paradise will be a kind of a library.” I think the way we choose to transmit our experiences to others and live our lives in relation with other humans and the beyond can be seen as the performance of a book unfolding.

NDEREOM: Something I keep hearing, and which I disregard over and over, is that the ultimate fate of the physical book is to be replaced by its digital counterpart. You make books, as in artists’ books, and I also have done so in the past. Could you see your work in this field taking a digital shape and if so, at what expense? What would be lost/gained in bringing bookmaking fully into the digital realm? How do you cope with the reality that, while most artists’ books are still physical objects, they are usually not allowed to be touched by the public? I find a dichotomy in this. What would it take to release artists’ books into the hands of anyone willing to engage them?

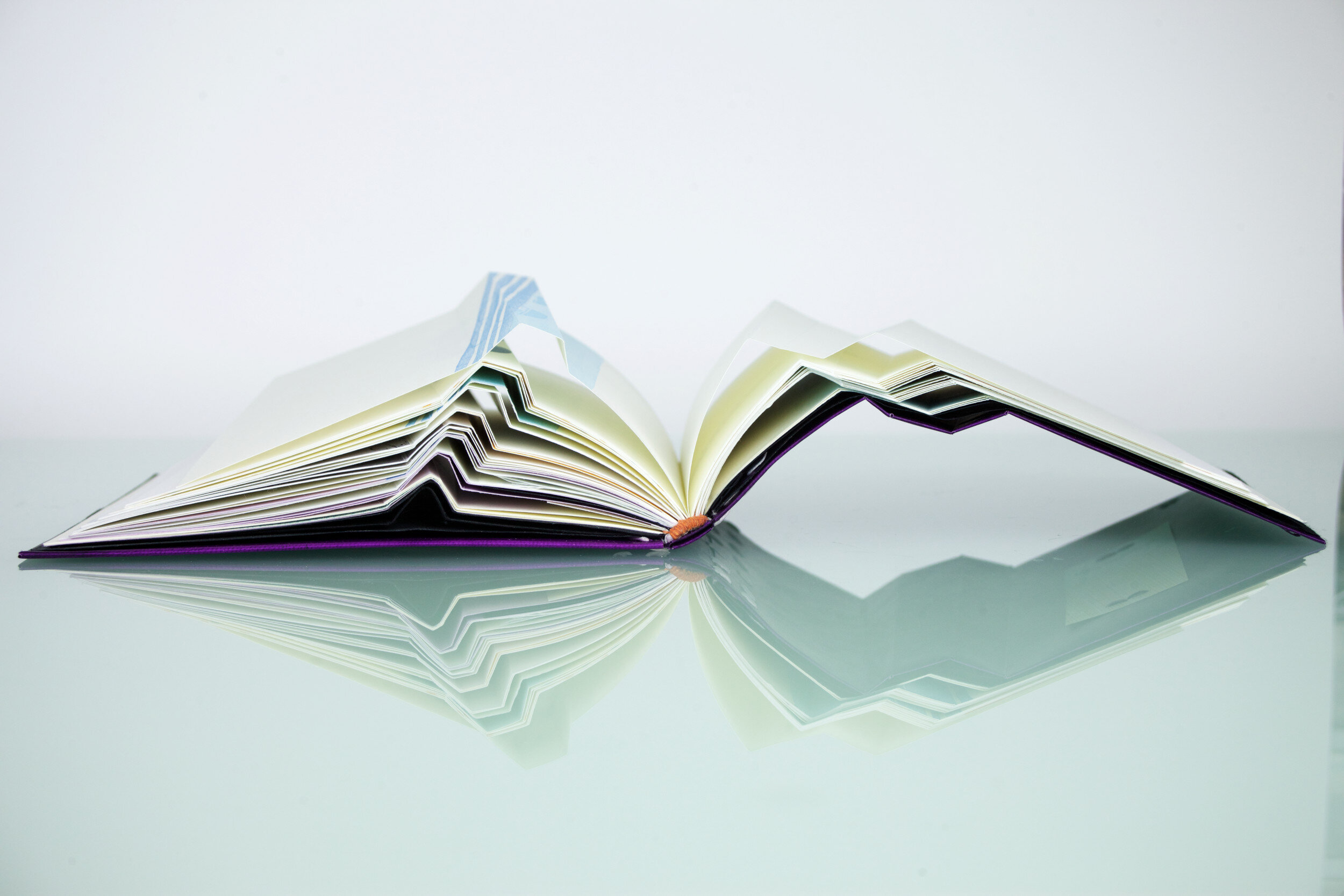

ADAS: I don’t see my artist books taking solely a digital shape. I can imagine my work as a physical book being shared as open source in a digital platform, especially if information is not accessible to people. However, in my view, the overall experience will be limited. For me, one of the joys of making books is the time and care spent choosing physical materials like paper and ink to carefully convey ideas through tactility and how these physical materials become content. Every page dimension, paper texture, color and weight, deckle or straight cut edge gives meaning to the reading of an artist book, inviting us to engage with its haptic qualities. As humans, we recall our memories more easily and with greater detail the more of our senses are involved in the initial experience.

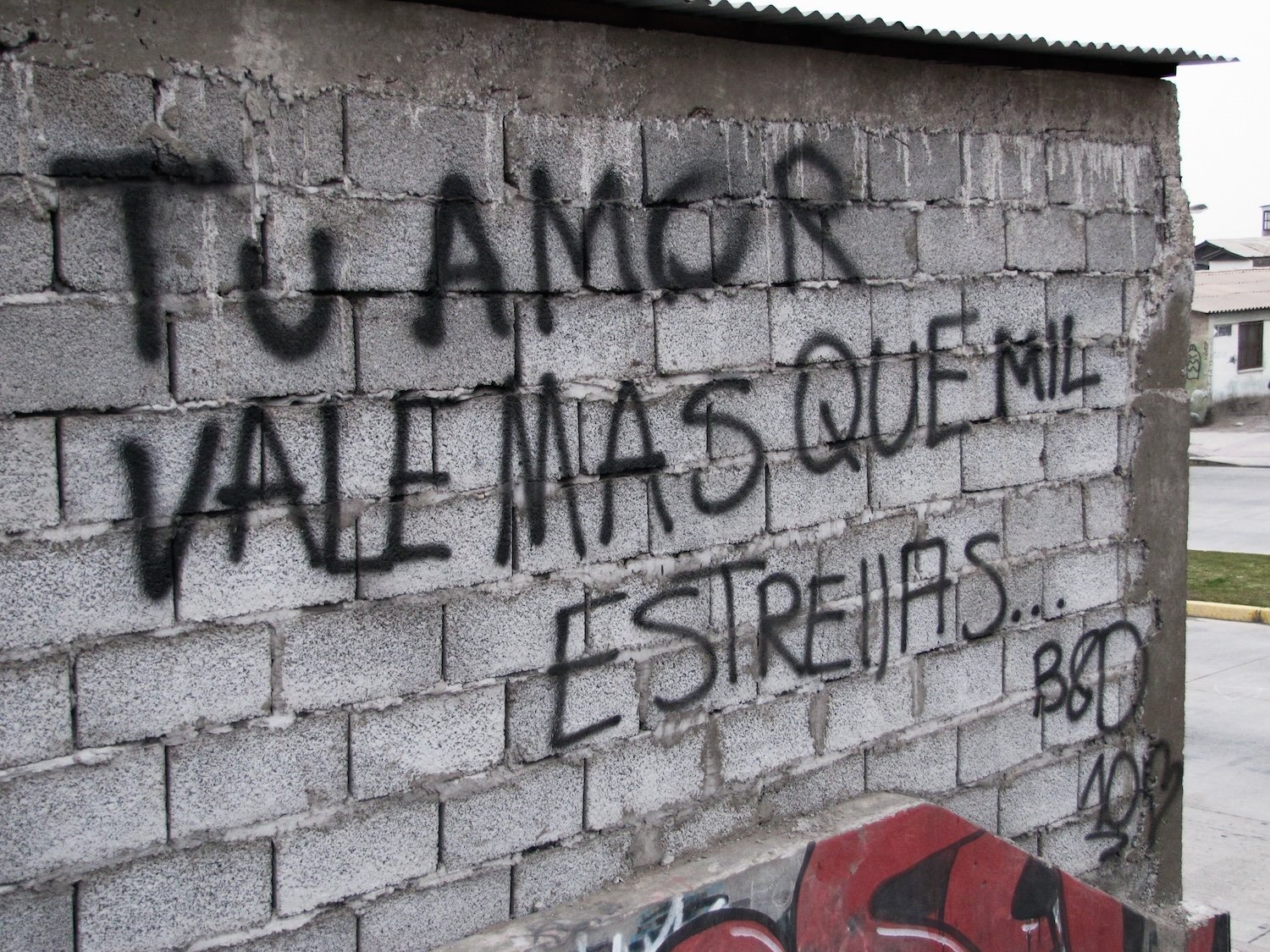

In 2016, I was asking similar questions, inviting poets Lourdes Gil (1950–2023), Iraida Iturralde, Cecilia Vicuña, and Jennifer Tamayo to both respond to the book as a physical object and to imagine a world without books. This was in direct response to seeing how many Spanish bookstores in Little Spain, NYC were closing as real estate prices were skyrocketing in the city. I frequently visited these Spanish bookstores when I lived there.

I also haven’t found a solution for more viewers to touch my books, especially when they are exhibited at institutions and insurance and liability become an issue. I find it really inspiring when I can just show my books to friends in my living room. Book fairs, (educational and commercial events), offer a way of engaging with books in which people can meet the makers and authors of artist books. I am thinking of Codex in California, Printed Matter Book Fair at MOMA and Art on Paper in NYC.

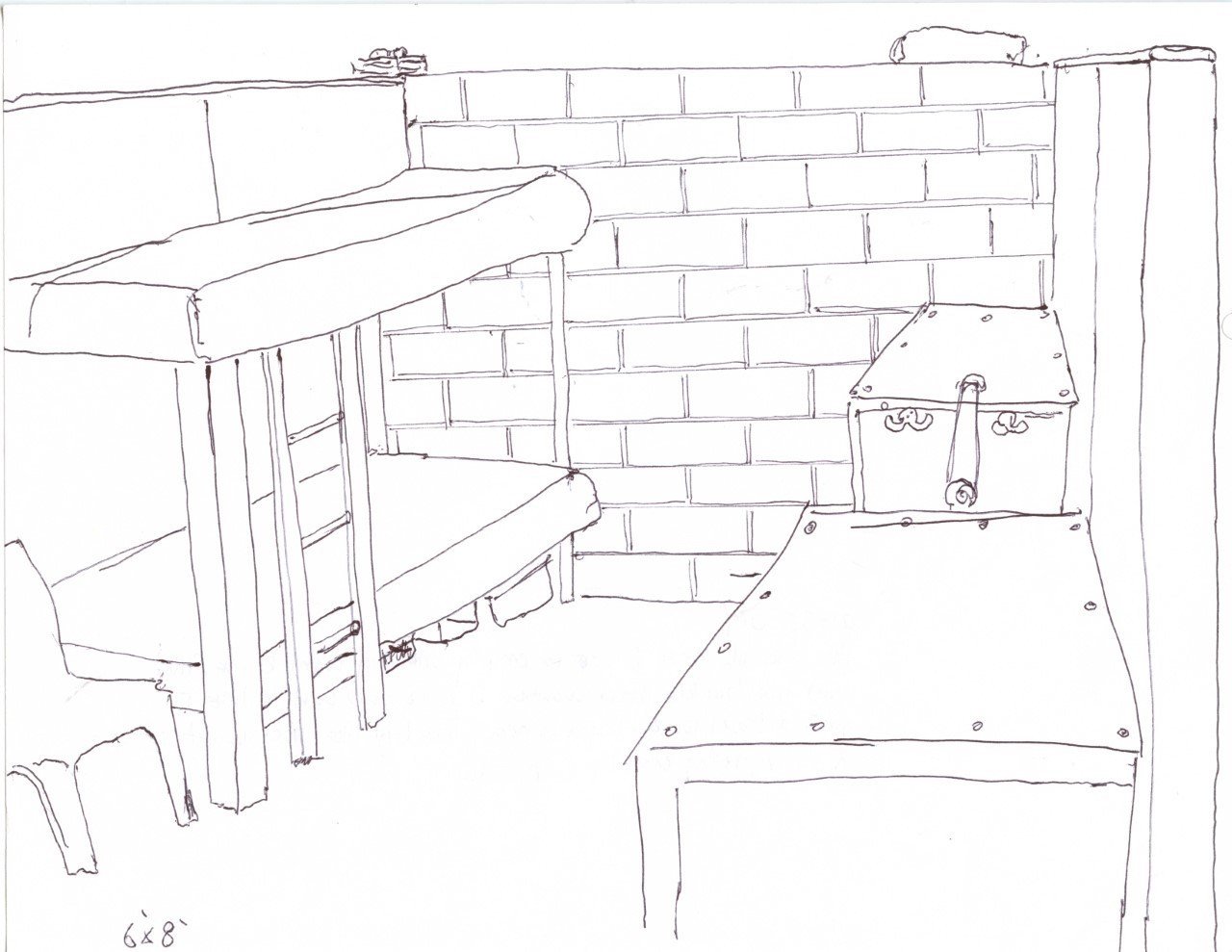

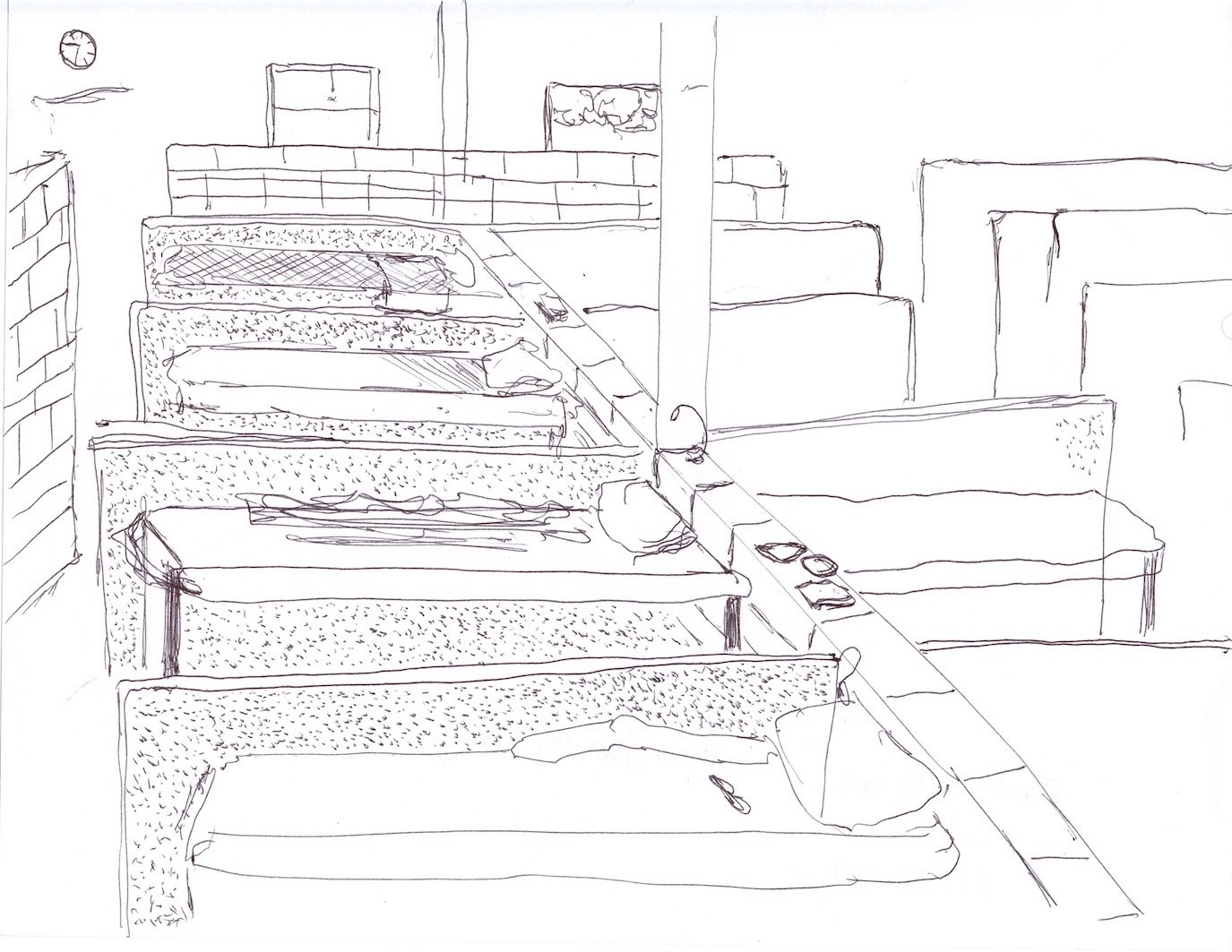

NDEREOM: I do remember Macondo, and Lectorum on 14th Street; now gone. Let’s jump into life and politics with the understanding—perhaps I should say my understanding—that all artworks are political because they are not generated in vacuum. You story about living at Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp is something I learned as I researched your creative practice in preparation for this conversation. In a way, you were a refugee in your very own country, Cuba. This experience was the impetus of one of your books: Libro de las Preguntas / Book of Questions. Can you please talk about this piece and the context that gave rise to it?

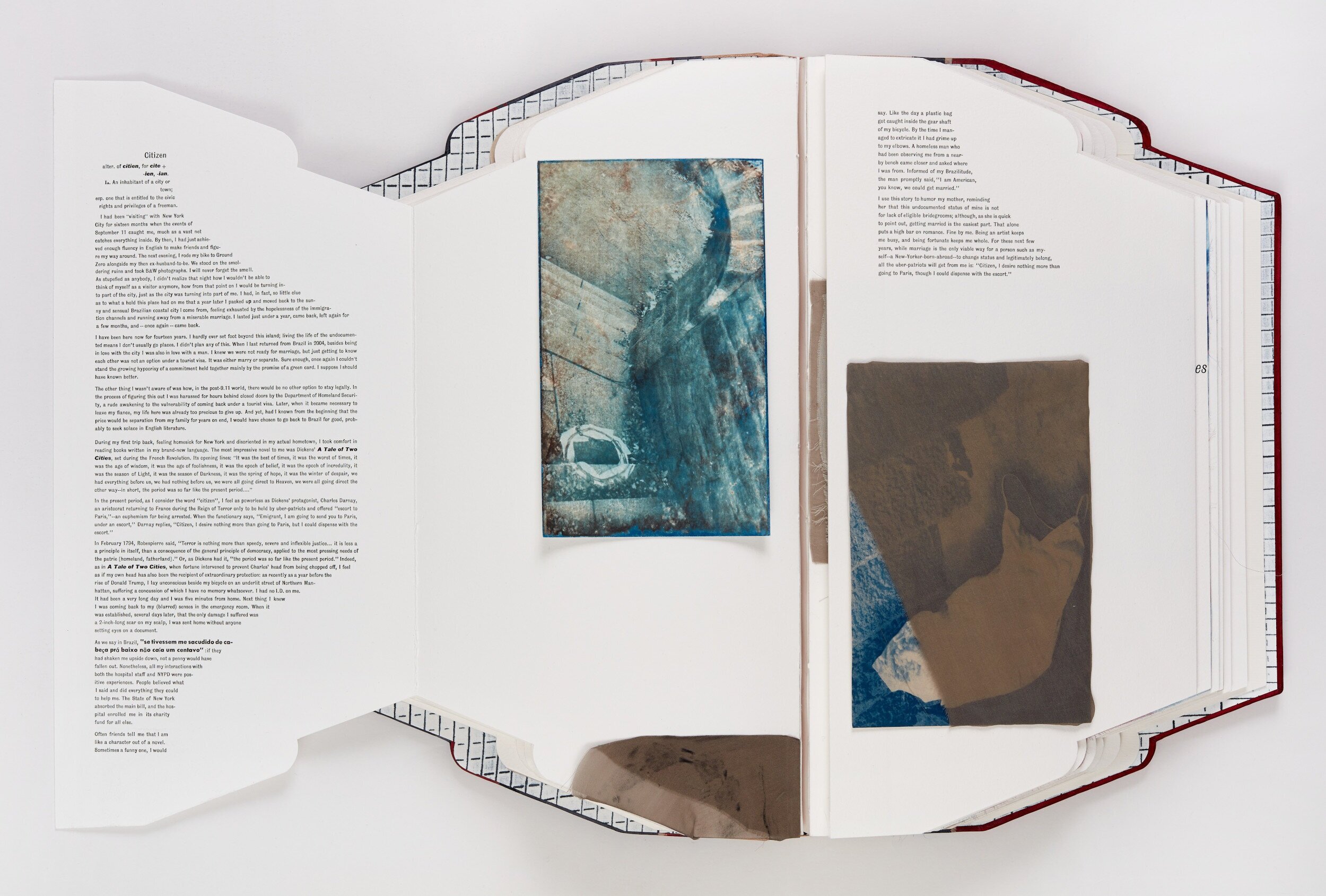

ADAS: A Book of Questions – Yon Ti Liv Kesyon – Libro de Preguntas is an artist book comprised of questions directed toward three groups of people (Haitian detainees, Cuban detainees and Guantánamo Bay administrators and soldiers) whose paths intersected during the early 1990’s at GTMO. It is a gesture of memory and reconciliation; of remembering together. I wrote the questions in Spanish, and they were translated into Haitian Creole and English with the help of family and friends including Iraida Iturralde, Rejin Leys, James Kelly, Bano, Angel A. De Armendi Sobrino (my brother); original questions and translations were printed for the artist book. The project was inspired by a photograph given to me by a soldier one day at the camps. I was browsing my family archive to share it with the Guantánamo Public Memory Project in NYC and an image caught my attention, a portrait of me next to a Marine, I was 14 years old. I remembered the day when the soldier called me as I was walking in McCalla 2 camp to pose next to him for a photograph. Days later, he came over to my tent to give me the printed image. I don’t remember his name, and nothing is written on the back of the photo. Looking at my photo, I started to think about how did we (Cubans) perceive them (Marines), and how did they (soldiers, health care physicians, volunteer teachers, translators) perceive us? And how did we (Cubans) relate to the Haitian refugees already living in the detention camps at Guantánamo before the Balsero Crisis of 1994. At the early stages of this project, I had a goal… I was looking for definitive answers to a set of questions I wrote for the different groups, yet, as I encountered more stories, I realized that some of the refugees and some of the employees were not ready to talk about specific issues, sometimes sharing a photograph is easier than the act of speaking and sometimes posing the questions was enough of a gesture for individual remembrance and introspection.

In the summer of 2013, I stumbled across El libro de las preguntas by Pablo Neruda, which is comprised of poems in the form of queries that convey greater meaning about the human condition. These three questions below were appropriated for my project from Neruda’s book:

How many weeks are in a day and how many years in a month?

Where is the center of the sea? Why do waves never go there?

How long do others speak if we have already spoken?

These questions reminded me of how refugees’ perception of time at the camps was challenging as we didn’t have information about how long we were going to remain in detention. The second question points towards the shared experience of crossing the ocean with the hopes of arriving in a host country, the third question for me speaks of the importance of speaking or sharing a story when ready.

These are some of the questions I letterpresses-printed in my book:

What sounds do you remember?

Where you an employee or a refugee?

How long did you live at Guantánamo Naval Base, Cuba?

Do you have a photograph or a document that illustrates something beautiful that you

experienced during the time that you lived at Guantánamo Naval Base, Cuba?

What were your fears, what were your hopes when you arrived?

How would you describe the landscape at Guantánamo Naval Base to a person that has

never been there?

How old were you when you lived at Guantánamo Naval Base, Cuba?

Do you remember when you left the base? To whom did you say good-bye?

NDEREOM: Immigration is such a taboo word in the United States at a moment of isolationism and fear of the Other as it pertains to whiteness. Those of of us who can still think critically and with interdependence in mind, are aware of the destruction of families and communities, as considerable numbers of people are abruptly deported. Immigration has been central to the Caribbean, where I dare to say that places like Cuba and the Dominican Republic have experienced a cultural, spiritual, gastronomic…syncretism that leaves almost anyone in the US perplexed. Places like our homelands have been the crossroads of the planet, irrespective of their relatively small size. There is nothing comparable to this in the US and I am thinking of books like Antonio Benítez-Rojo’s The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective. With all of this intersectionality in mind, can you tell me about your work as it pertains to the legacy of the late Ana Mendieta?

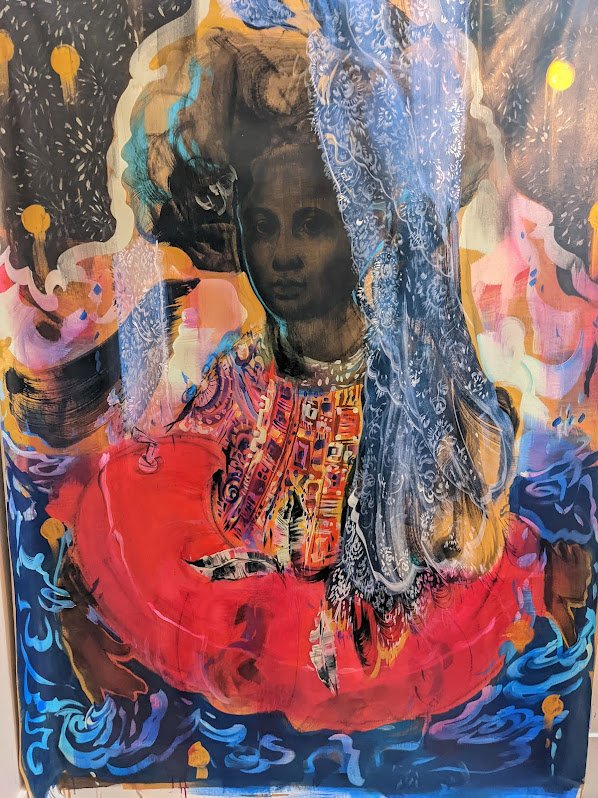

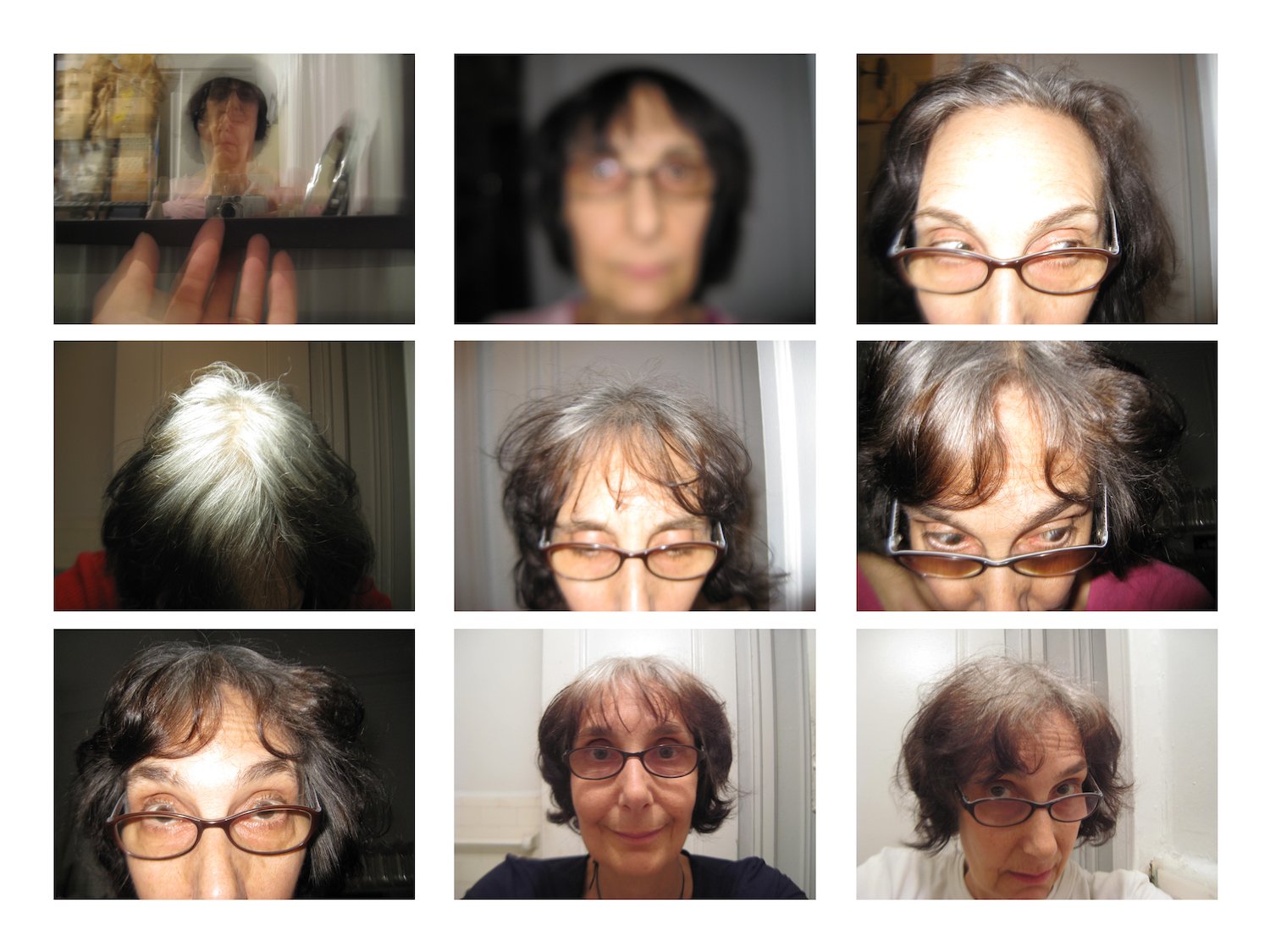

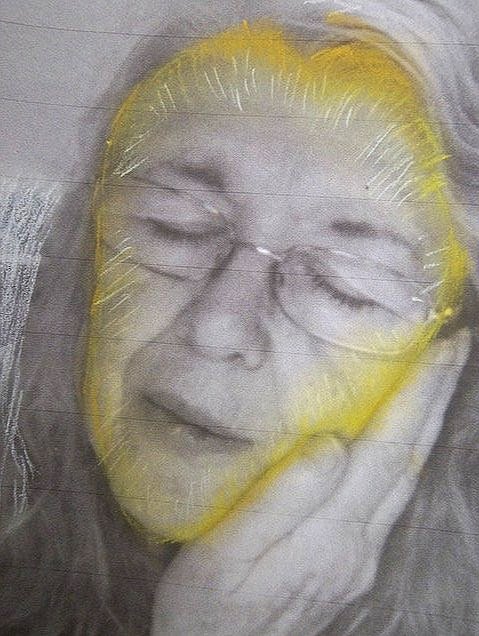

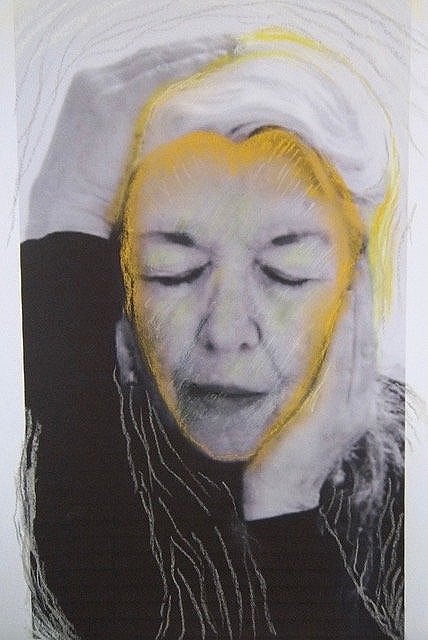

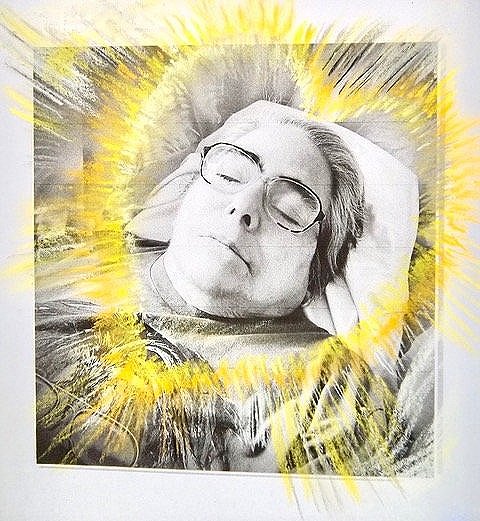

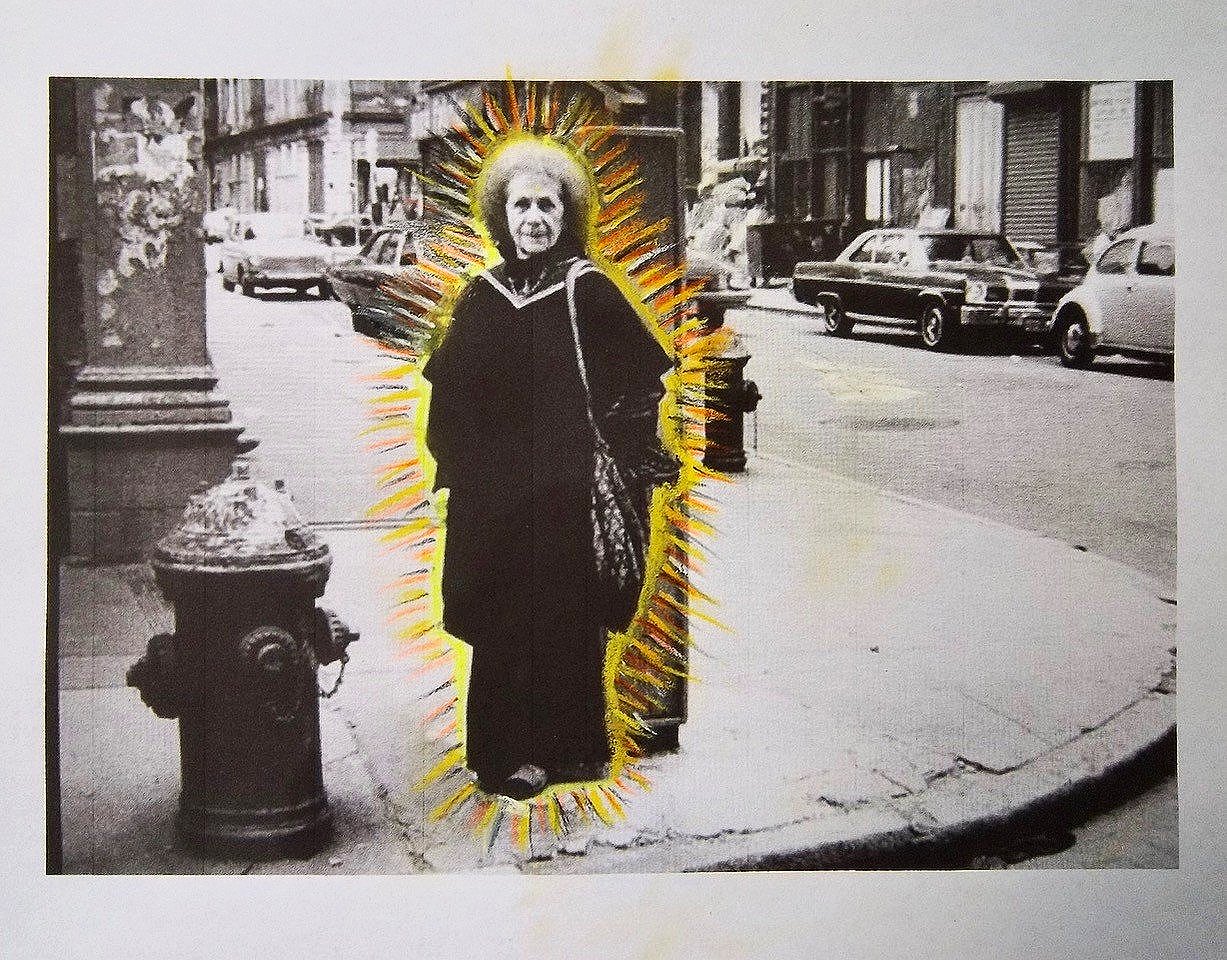

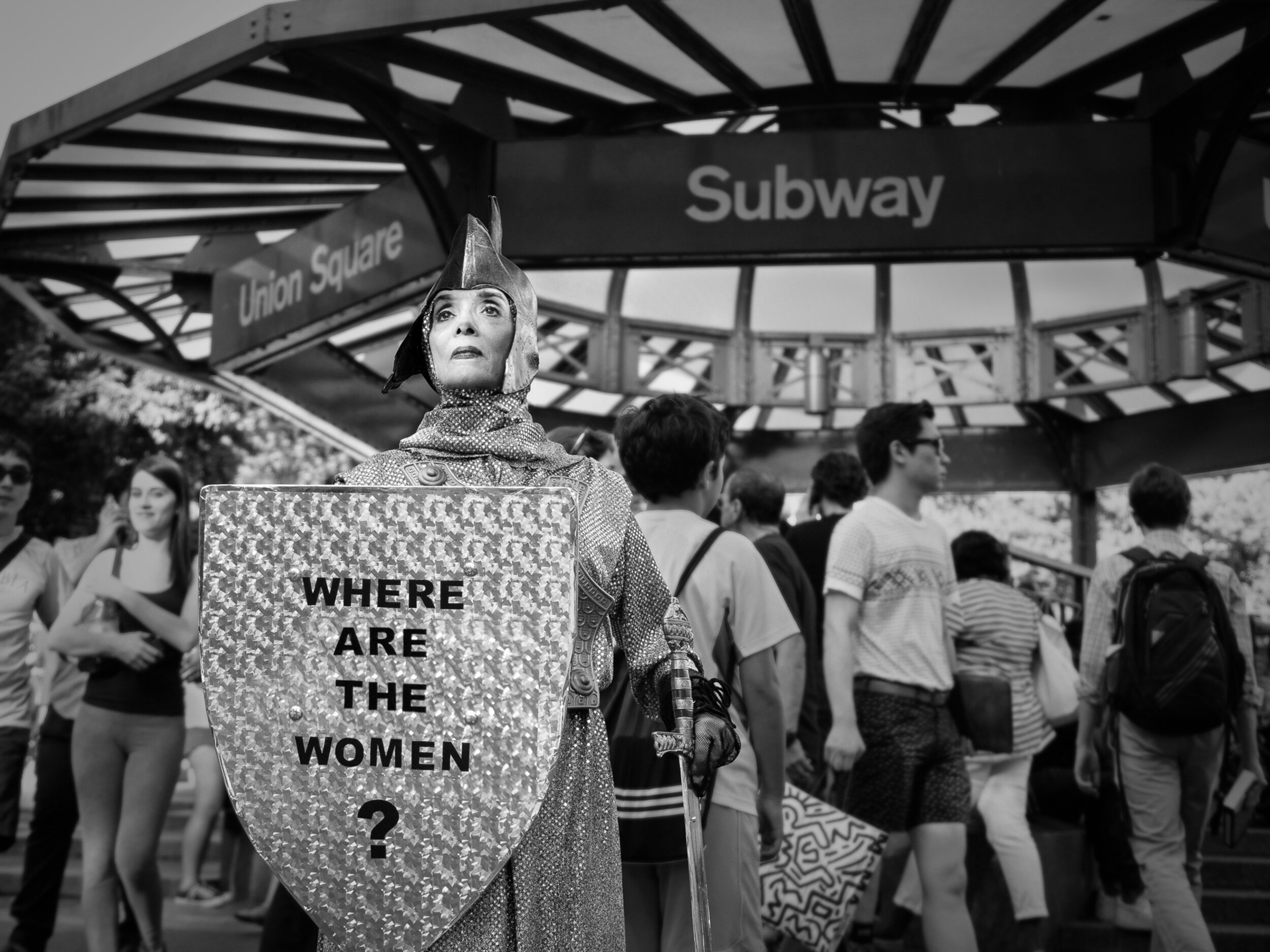

ADAS: This is a very complex question …Ana Mendieta’s artistic legacy is rich, powerful, and tragic. In her art, there is a palpable authenticity and courage in the way she expressed her human existence as a woman, immigrant, sister, artist. When I first learned about her work, I was in my early 20s, a young art student at Cooper Union. I had recently moved from Miami to NYC, away from family, struggling still with the English language and finding my way through the American education system while attending a very rigorous art school. So much of it was foreign to me. When I first saw Mendieta’s art, I was moved by it, experiencing so many emotions, grief, anger, love, hope. I also perceived so much violence and pain together with a unique creativity and tenderness in her pieces. At the time, I was studying art history with art historian Dore Ashton (1928–2017) and decided to learn more about Mendieta’s life and her Silueta Series as well as the influence of Octavio Paz and his book El Laberinto de la Soledad on her work. Ana was a Peter Pan Operation child sent by her family to the United States with her sister Raquelin Mendieta at age 14 and taken to Dubuque, Iowa. She lived in foster homes and orphanages until she was able to reunite with her mother after years of separation. She and her sister endured emotional and psychological hardships during this time. I read everything I could find on her life and art and met people who knew her in NYC, Miami and later when I studied at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, her alma matter. Poets Lourdes Gil and Iraida Iturralde, artists Hans Breder (1935 – 2017) and César E. Trasobares, and my teacher Dore Ashton among many others shared personal stories of their life interactions with Ana.

Looking back as an adult with more awareness, I saw aspects of my life story (younger self) mirrored in her life story. I understood how art allowed me to survive and continue to heal, I also saw this in Mendieta’s art. My artistic work has explored diasporic sentiments, grief, resilience in the face of hardships, hope, joy and finding a way to belong. Ana Mendieta’s courage to explore her identity, to speak up about gender inequalities in the art world and to honor her creative expression from the perspective of an immigrant woman encouraged me to do the same.

Humans have moved since the beginning of time. Every person internalizes immigration differently, those that haven’t had that experience don’t fully understand what happens in this event, especially if immigration is traumatic and takes place against the person’s will, for safety reasons and at an early age. In this process, there is so much grief due to the separation of families, longing for the land that nourished the individual from an early age, the loss of language, loss of friendships and culture. This experience not only affects the person who leaves but also those who stay behind. This uprootedness becomes deeper and more painful if the individual is not given the support and time to grieve and find safety to belong to themselves again before finding belonging elsewhere. Time to heal for many immigrants is not an option, at least at first, most of them, as you may relate to, live in survival mode for many years after emigrating without a way of processing their personal trauma and regulating their nervous system.

In Mendieta’s ritualistic gesture of making her Silueta Series, she expressed her longing to return to the source, to become one with the earth. She said, “my art is grounded in the belief of one universal energy which runs through everything.” For me, her repeated return to the earth was a way to claim her life energy, to leave an imprint of her body on the land, protesting self-erasure and pointing to the illusion of separation… again emphasizing the “universal energy that runs through all of us.”

NDEREOM: I am curious as to how your impetus to awaken and actualize some of Ana Mendieta’s narratives, and in specific the Taíno ones, transcend an approach that I have seen some Cuban artists take, and that to me translates as scaffolding. Ana Mendieta, in the case of what I call scaffolding in the art world becomes a validated referent that can be easily used as a stepping stone. I am not at all implying that this is your case and that is why I would like to hear directly from you. How are you dealing with such charged materials?

ADAS: In NYC, I continued to learn about Mendieta’s life and art, and came across a proposal for an artist book she was working on in the early 1980s. My interest in her work led me to study at The University of Iowa, the same university she attended, and to pursue a minor in the Intermedia program where she made much of her foundational work. I also decided to study in Iowa City because I wanted to go deeper into the practice of printmaking, papermaking and book arts. While doing more research, I learned via my uncle Rafael that my paternal grandfather Rafael Angel de Armendi y Quirós (1911–1976) was good friends with Ana Mendieta’s paternal great uncle who served as provisional president in Cuba, I believe for two years. Based on my uncle’s stories, they both loved white roosters and were passionate about politics. I have a picture of them together. My father was also born in Jaruco and has family still living there in Cuba.

In the late 1970s, there was an interest to restore relationships between the Cubans living in the island with the exiled Cuban community. Many Cuban humanitarians, poets, artists began these conversations and flights began to take place from Miami to Havana. This was the time when Ana Mendieta decided to re-connect with her ancestry, identity and the Cuban artist community, traveling to Cuba and bringing American artists with her. There is a very animated photograph of her in Cuba with Lucy Lippard, Gerardo Mosquera, José Bedia and other artists taken on January 14th, 1981. Mendieta ended up working on many sites in Cuba including Varadero, Cayo Coco, and at las Escaleras de Jaruco. She intended for her artist book to be finished in 1983, and it was going to be published, advertised and distributed by Printed Matter in NYC. Lucy Lippard was one of the founders of Printed Matter, she and Ana had previously collaborated on a show Lippard curated in 1977 titled Contact, Women and Nature at the Hurlbutt Gallery in Greenwich Connecticut.

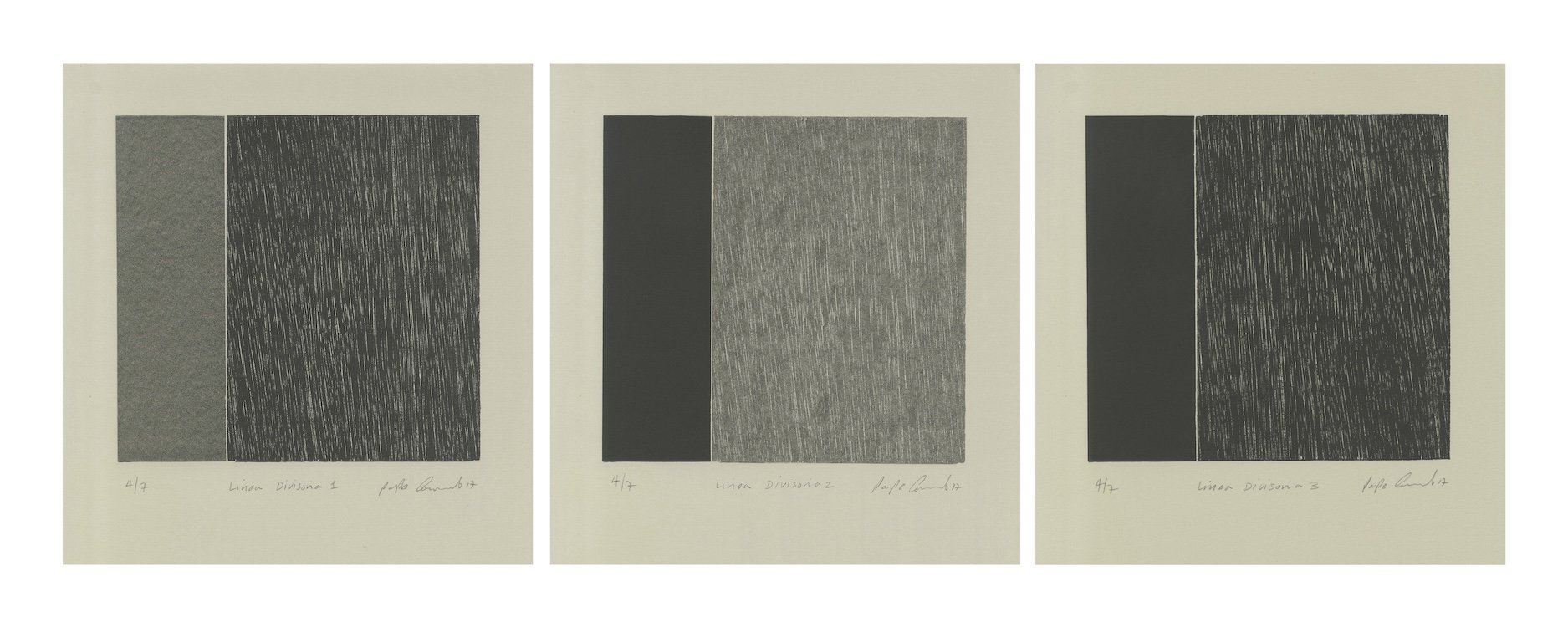

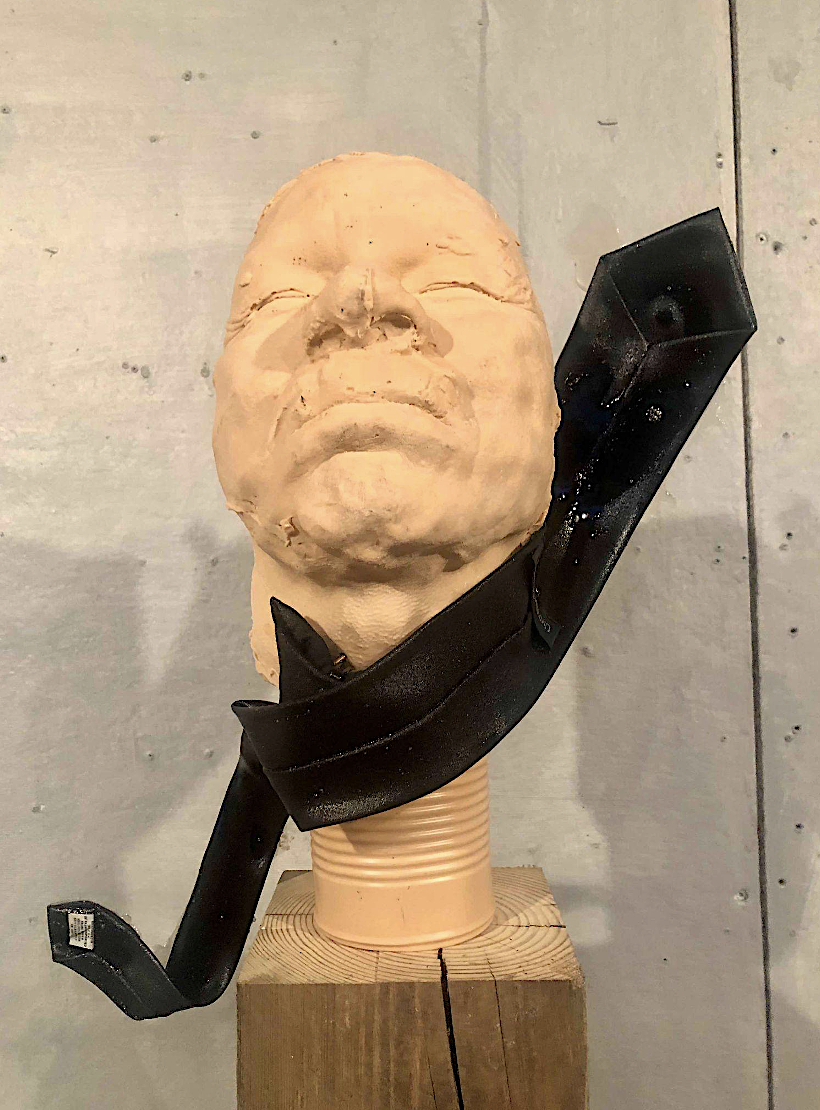

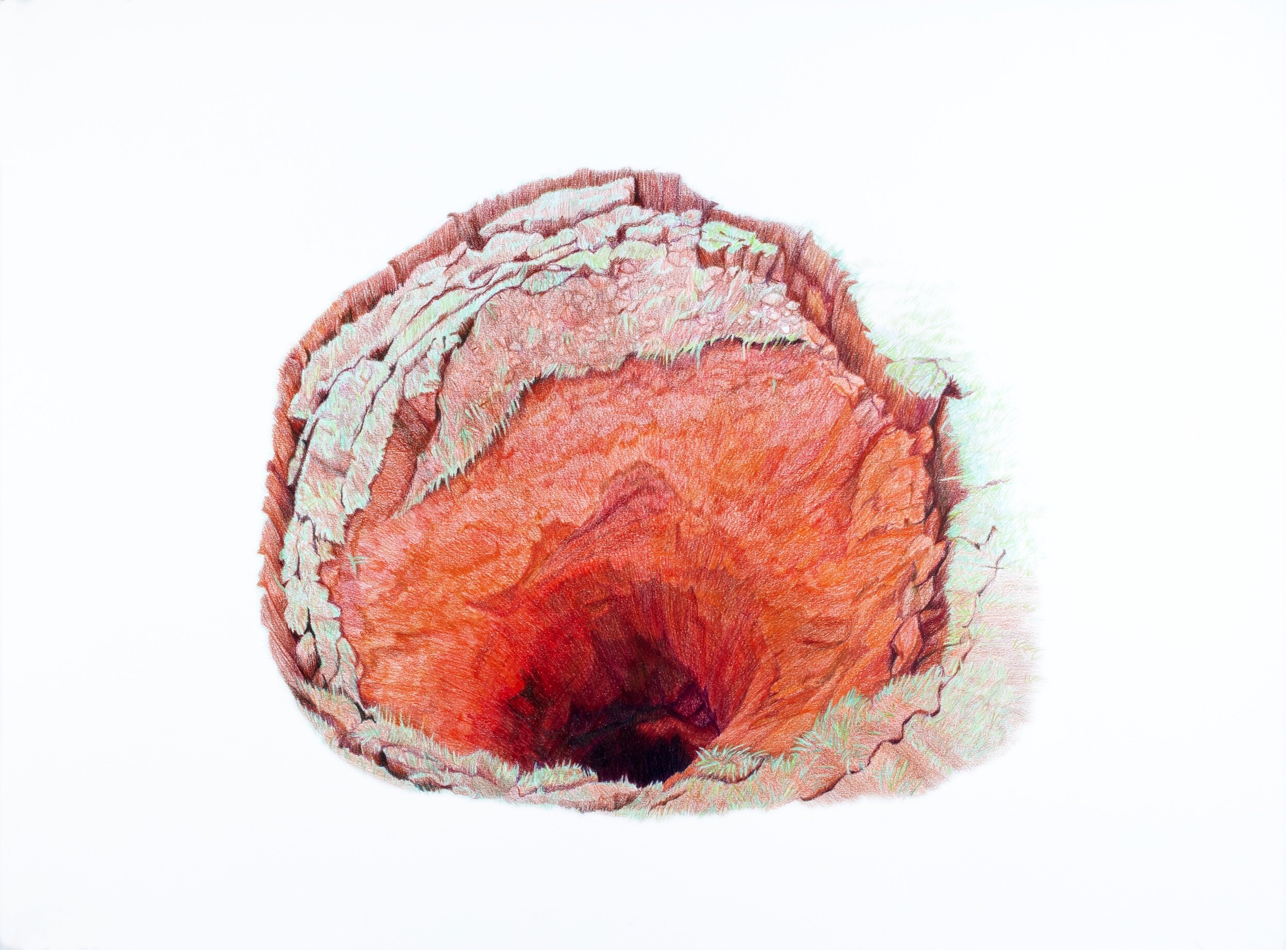

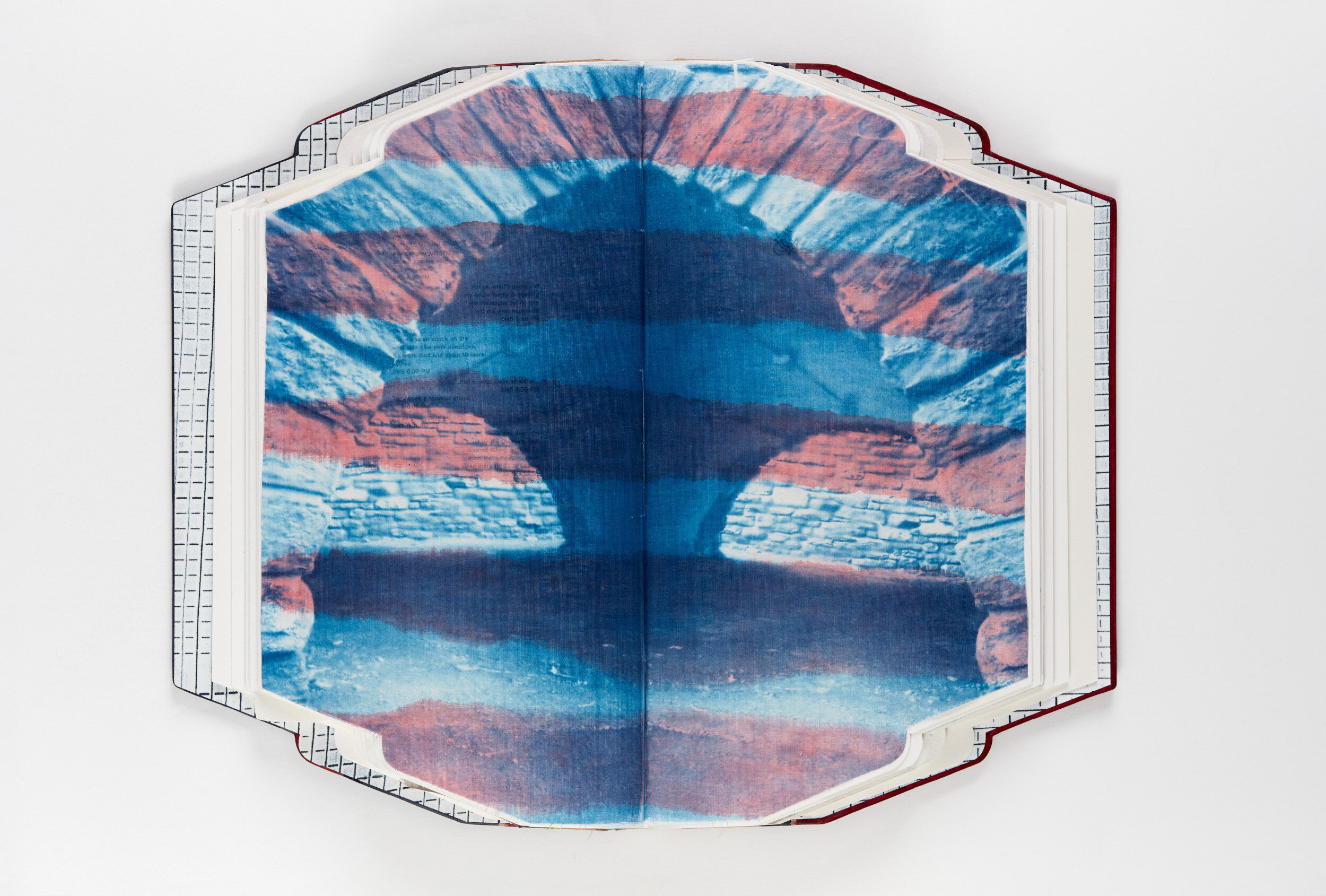

In the summer of 1981, Ana Mendieta worked at las Escaleras de Jaruco, a national park outside Havana. Inside the limestone walls of the caves, she carved low-relief sculptures, naming her pieces after Taíno female deities: Iyaré (Mother), Maroya (Moon), Guanaroca (The First Woman), Bacayú (Light of the Day), among others, and gathering them under the title, Rupestrian Sculptures Series. In 2012, I traveled twice to Cuba, in January and in June to document and study the carvings Mendieta had made in 1981. Mendieta photographed these works and as I mentioned above, she intended to publish a book of etchings titled Rupestrian Sculptures Series; José Juan Arrom (1910–2007), then professor of anthropology at Yale and author of Mythology and Arts of the Prehispanic Antilles (1975), a work which deeply influenced Mendieta, was to write the preface for her artist book.

Due to her tragic death in 1985, Mendieta did not finish the project. She completed only five of the twelve sets of photo etchings she had originally conceived, and signed only one of the completed portfolios, now held at the Art Institute of Chicago. Galerie Lelong in charge of her estate hired Liliana Porter to print the rest in 1993, which was followed by Clearwater’s facsimile edition, Ana Mendieta--A Book of Works (1993).

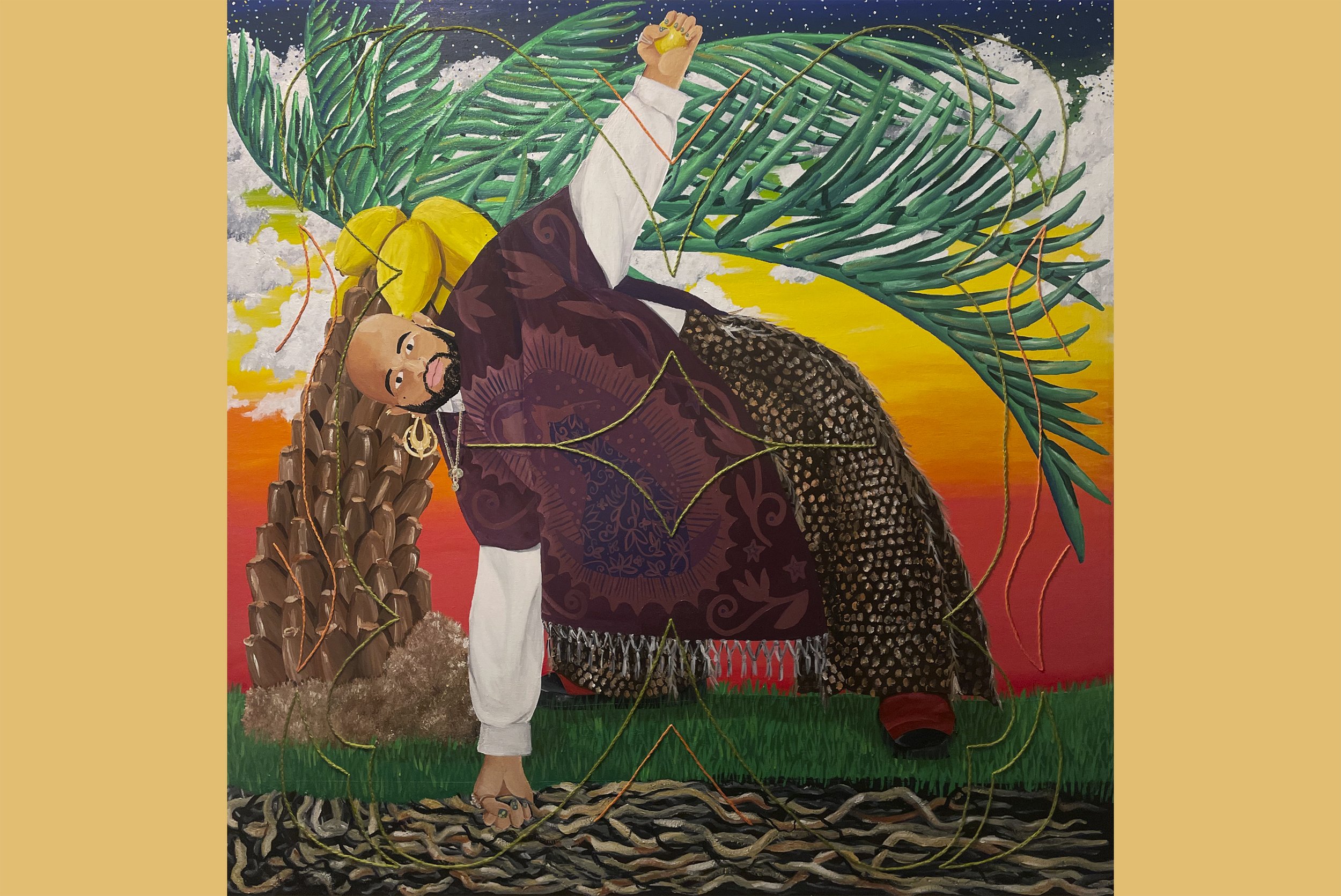

Mythologies of Return: Revisiting Ana Mendieta’s Rupestrian Sculptures is a limited-edition artist book. It is my way of honoring Ana Mendieta’s Rupestrian Sculptures and her original proposal of making an artist book of this series. I invited professor Andriana Méndez Rodenas to write a scholarly essay entitled Mythologies of Return: The Taíno Route in Ana Mendieta’s Rupestrian Sculptures which I designed, and letterpresses printed for this book. This project had many challenges, and even though it took me almost a decade to complete it, I’m very proud of it. It deeply connected me to Mendieta’s legacy, her Rupestrian Sculptures, my own understanding of the Taíno people and our ancestral identity as women born in Cuba.

NDEREOM: Your Libro de Colores! Without stereotyping, there is no other place on earth where I experience colors as in the Caribbean. Every time I travel back home, I am startled by the intensity of reds, blues, oranges, yellows.... It all seems so dull in places like New York State and the East Coast, color-wise. Would you be willing to discuss your chromatic education? What is your favorite color? What do you when the going gets hard, and when it being in touch with extreme bright colors becomes crucial to one’s wellbeing?

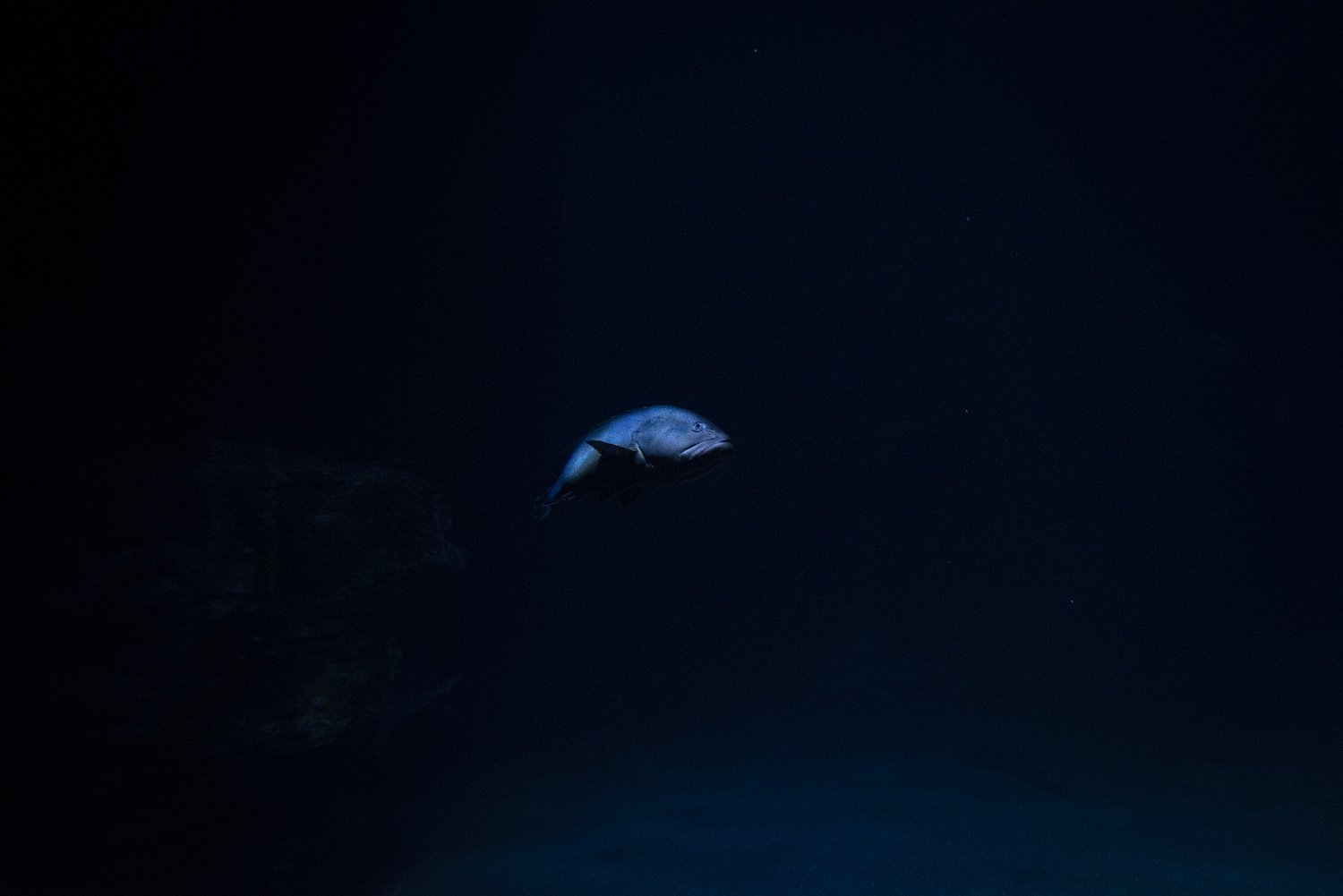

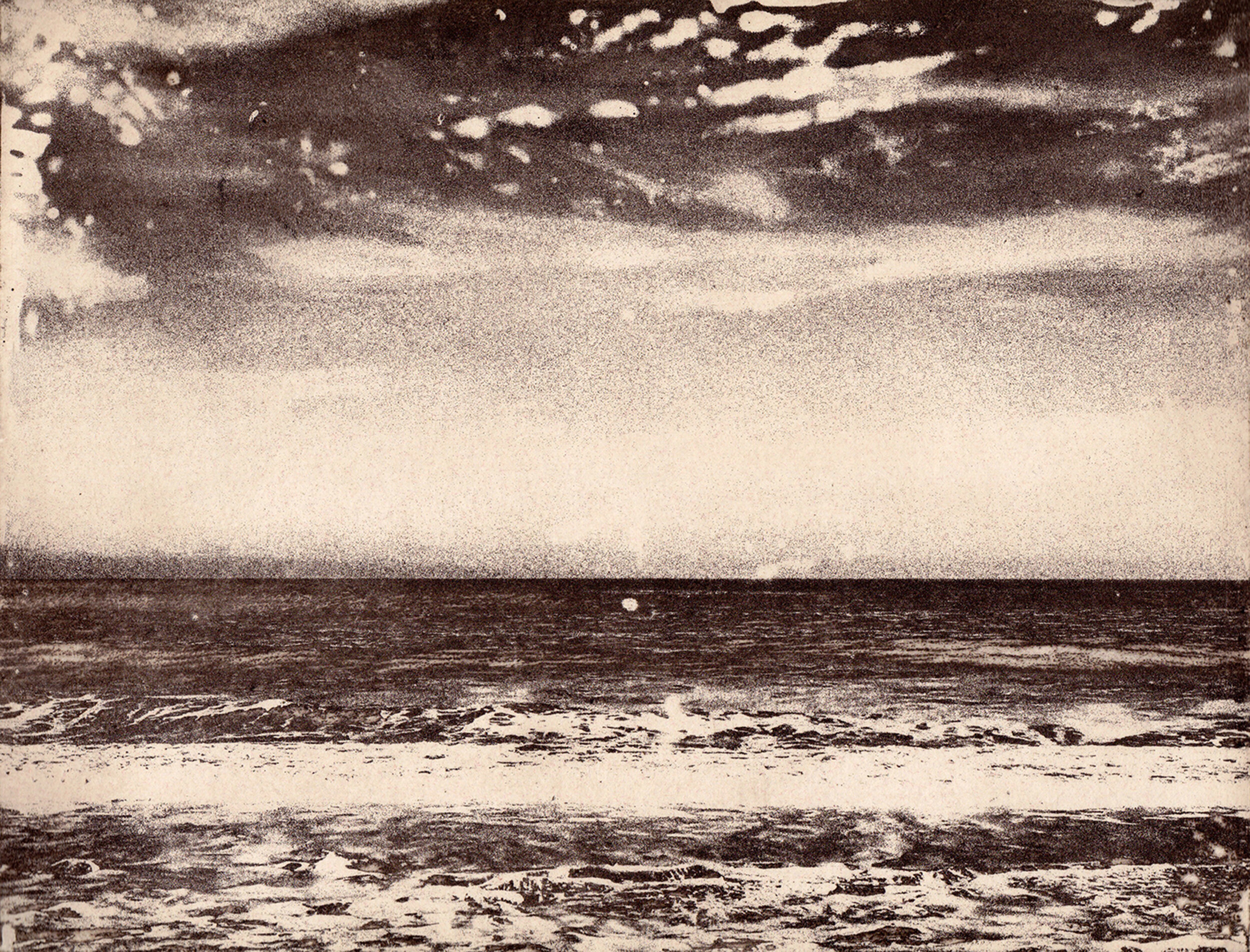

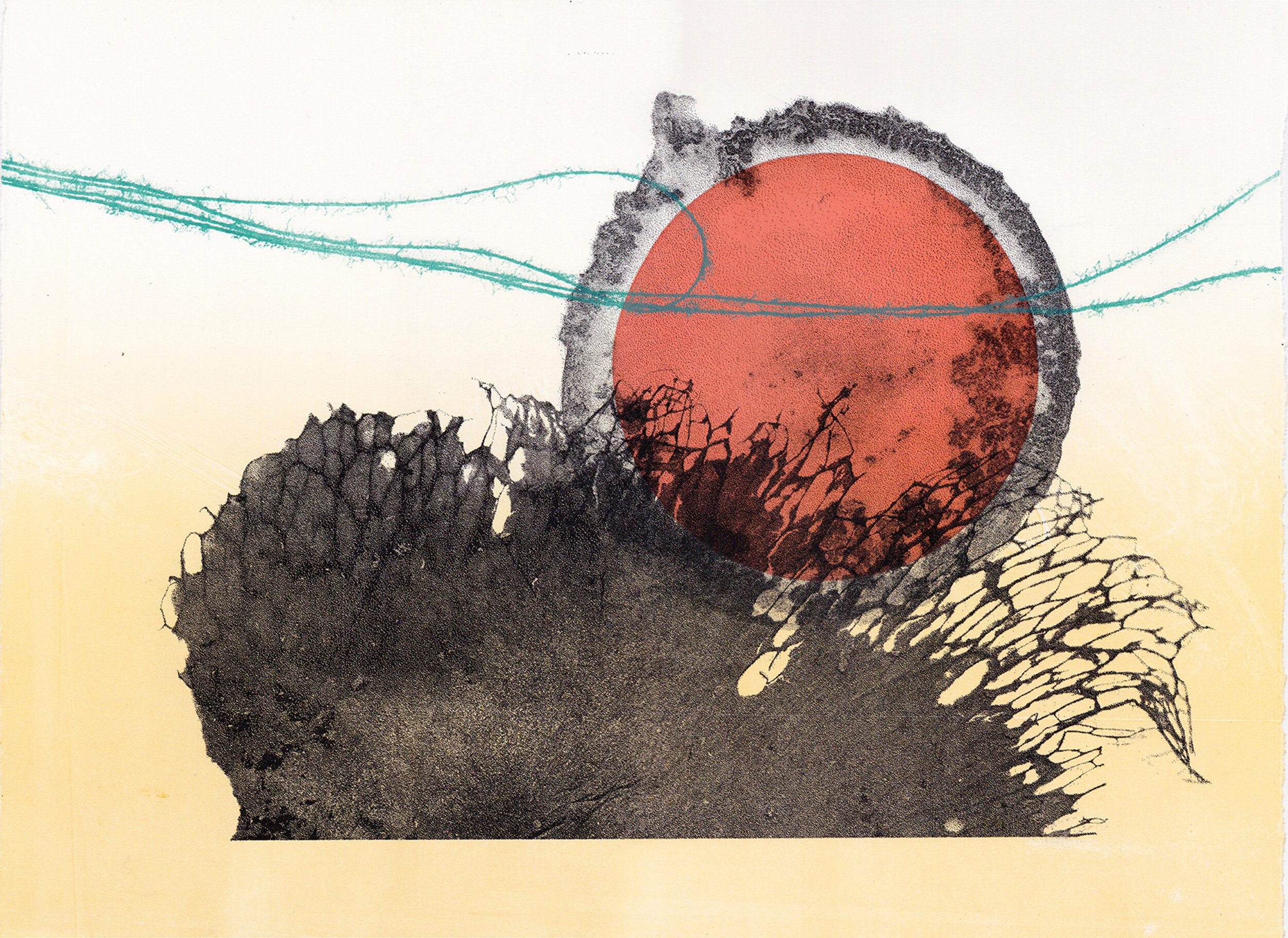

ADAS: It has been overwhelmingly beautiful to experience the tonalities of greens in the Caribbean. I have perceived these colors in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. I particularly love the red color of the Cuban soil/earth with all its pinks and purple tones. Libro de Colores: El Monte y el Mar is an artist book I made entirely of hand-printed monotypes on Kitakata paper. It is a double pamphlet structure, one book explores a gamut of green colors which, for me, is representative of el monte, the land… the second book is made entirely of blue tones, el mar. This work was my attempt to convey seeing the land from afar while at sea, when my family left Cuba in a raft in 1994, and the experience of light on that day. I wanted to create a color journey of a difficult and life changing memory.

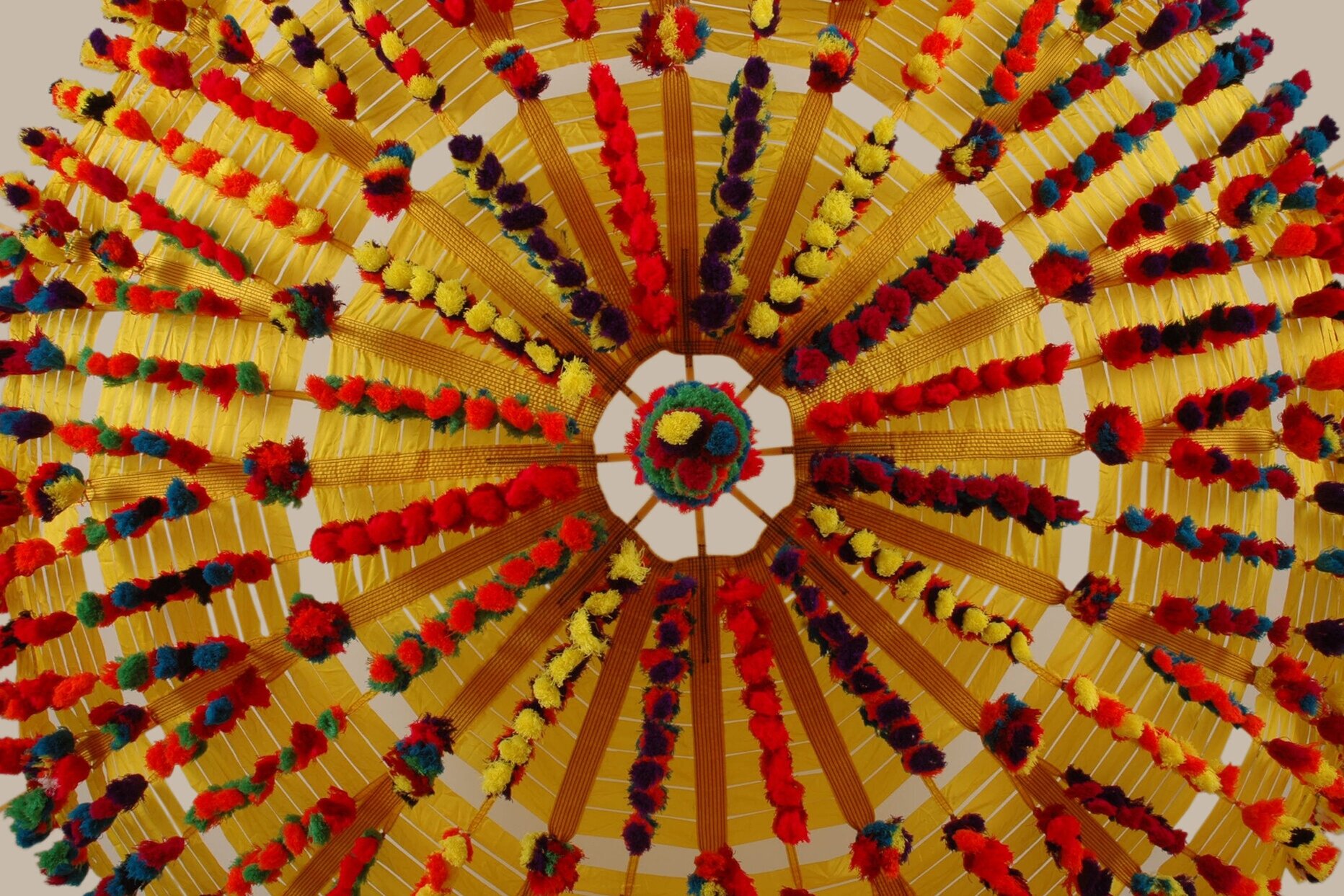

My informal chromatic education comes from spending time in nature since an early age: running bare feet, collecting leaves, being among trees, plants, flowers, playing with stones, earth, swimming in rivers, going to the ocean, playing with seashells, seeing marine life and helping my maternal grandparents in their farm. Both of my parents worked, so in the summers they would leave me with my maternal grandfather Florentino Sobrino Hernández (1906–1994) and my maternal grandmother María Josefa Díaz García (1919–2012) as well as many cousins in Camagüey, Cuba. My most striking color memories come from this time in my life. I was very close to my grandmother, and being the second youngest of a line of cousins granted me permission to spend more time by her side. Almost every night by candlelight, because there was hardly any electricity, we would sit on the cold floor of her living room and make carpets. She taught me how to make a sharp stick from the guava tree to be able to make holes wide enough in the burlap to be able to insert each piece of cloth as we were designing the patterns in the carpets.

Formal chromatic education comes from my studies at the New World School of the Arts in Miami with artist Susan Banks for a year before moving to New York City to study at the Cooper Union School of Art. Susan taught color theory at the New World School of the Arts and I also learned to work in ceramics with her. At Cooper Union, I learned color theory from Italian artist Gian Berto Vanni (1927-2017). Vanni (he preferred to be called by his last name) studied during a Fullbright Scholarship with Joseph Albers at Yale University. Vanni was so knowledgeable about color, his charismatic energy and generosity was contagious. We mixed colors by hand using watercolors, oil paints, and traditional egg-tempera using dry pigments and egg yolk following methods of artists during the Renaissance. In his class, we also did all the exercises in Josef Alber’s book Interaction of Color. Vanni encouraged his students to work on collages with natural materials. The fall in NYC became a time to collect leaves in Union Square and Washington Square Park. Vanni had a loft in Soho, and he would divide his time between NYC and Greece. At the end of each semester, he would cook with his wife and invite his students to his loft to eat together. I have many memories of eating in their bench-like elongated wooden table. His loft was full of his paintings and I’m so fortunate to have seen them in person. He also illustrated a beautiful book titled Love, his unique way of using color and line to emphasize the story is breathtaking. I miss him.

Further education comes from mixing color in the studio to produce my drawings and prints and also during collaborations at Two Palms. I want to mention some of my teachers and mentors in ink mixing in the print studio, artists Lorenzo Clayton, Lorena Salcedo Watson, Amy Pryor, Alison Sahmel, Doug Volle, Craig Zammiello, and Yasu Shibata.

I also find inspiration in how artists/designers have worked with color. I recently saw The Green Interior (Figure Seated by a Curtained Window) from 1891 by Edouard Vuillard (1868–1940) at the MET, such a small painting in scale yet the energy of the work and green paint luminosity is so very moving. I particularly admire the color sensibilities and legacy of Amelia Peláez (1896–1968), Carmen Herrera (1915–2022) and Loló Soldevilla (1901–1971). The use of color in artists’ books, clothing and carpet design by Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979) are always an inspiration and the quiet pinks and blues of Agnes Martin (1912–2004) and Zilia Sánchez Domínguez (1926–2024) are whispers to the soul.

When I was young, my favorite color was blue. I think it is because I love the ocean so much. Now, as an adult, my favorite color is green. I think it is because I’m trying to open my heart more. When the going gets hard my safe place is to be among trees with the smell of moist soil in the air or reaching out and talking to close family members and good friends. Bright colors always lift my spirit.

NDEREOM: Tell me about bright colors! I need them as much as food. I will open the space for you to elaborate on the book that you produced and which pages are made out of clay.

ADAS: This body of work, the clay pages, point toward writing surfaces before the invention of paper. I was thinking of the Cuneiform writings on clay tablets in Ancient Mesopotamia. Also, I was looking and researching the collar stones made by the Taíno people while working on these pieces. I would knead the clay, make it flat and cut rectangles 8.5 by 11 inches. Afterwards, I would engage in playing with the material, I was free to fold the clay, to understand its breaking point, to feel its wetness and dryness, to feel the sensuality of working with my hands while touching the earth. I let the process determine the final shapes of the clay pages. During this time in my studio practice, I was looking and learning more about the Terra Modelada series by Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino… when talking about her series she says, “for me working with clay is an extremely pleasant, sensual process.” In my clay pages, I was also exploring the actual working, being immersed in the labor and enjoying the sensual pleasure of working in collaboration with the earth.

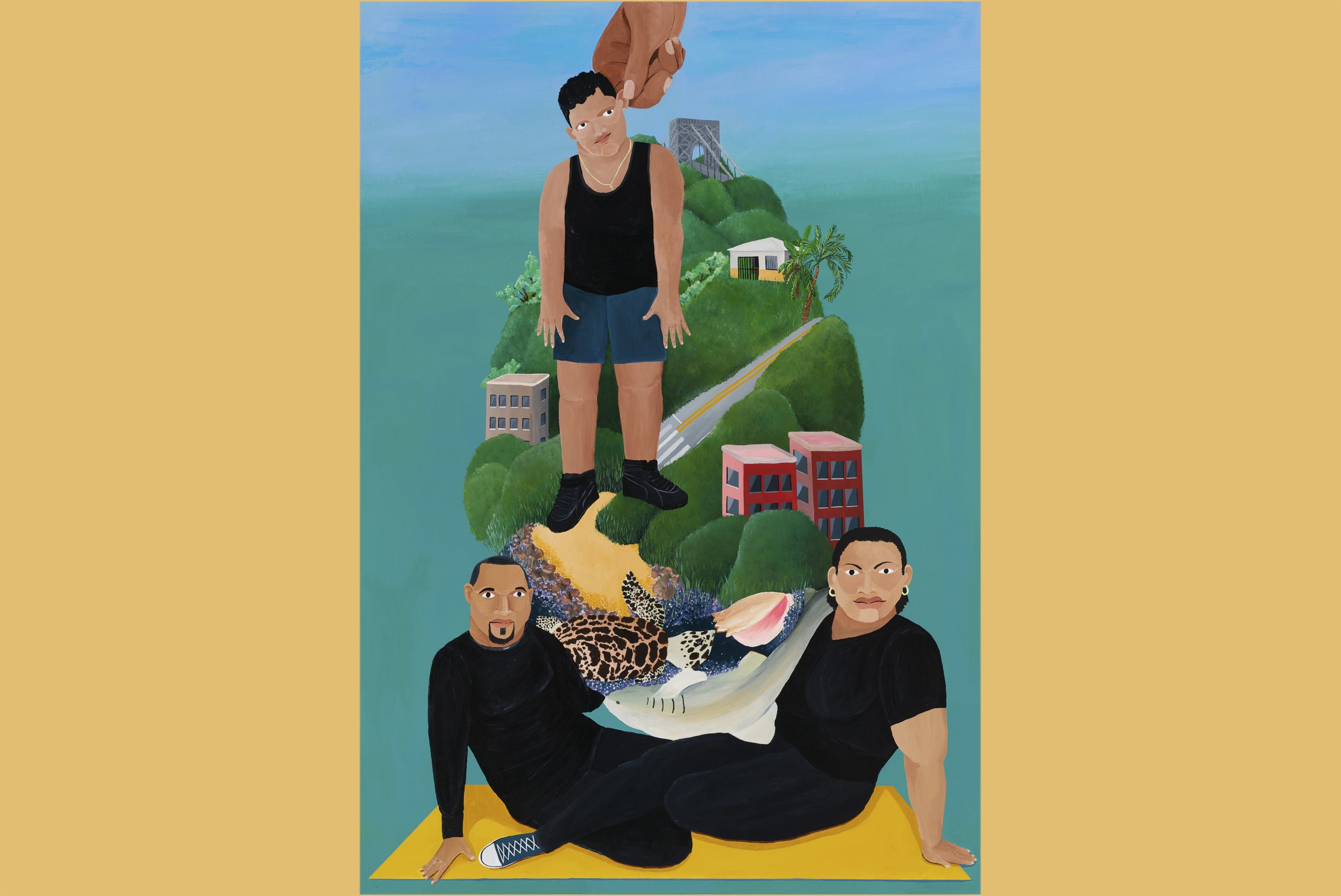

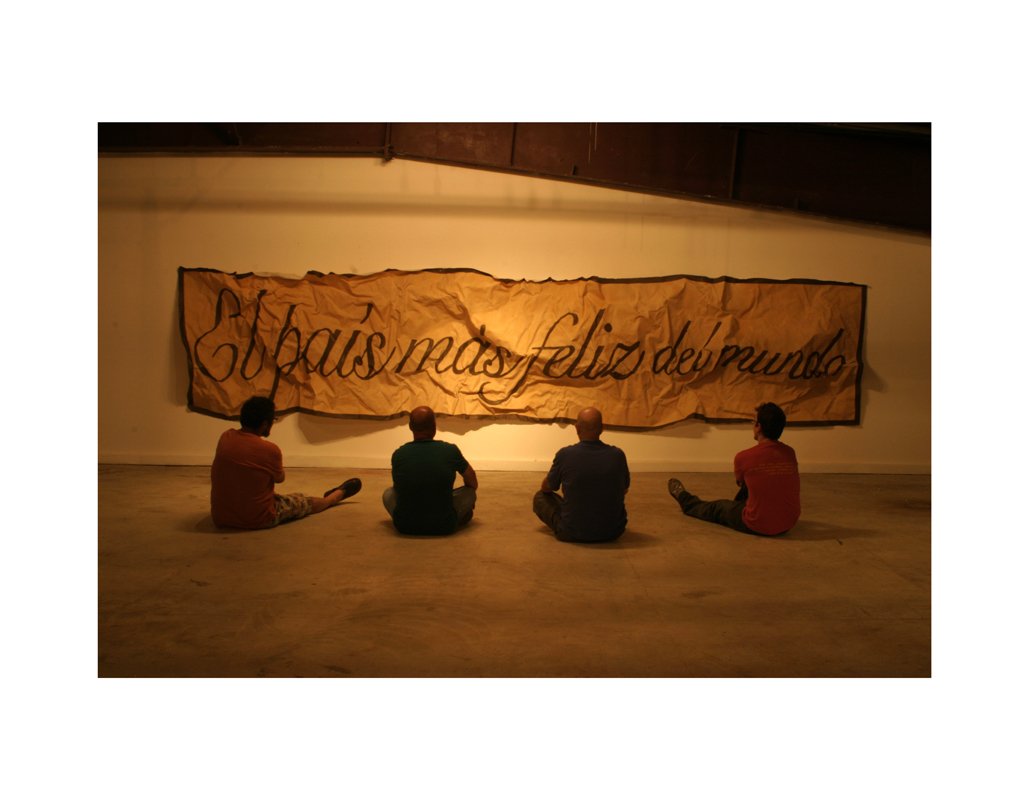

NDEREOM: I would think that the Cuba that you left in the 1990s was one different from the one that many of the exiles from the 1960s departed from. In my view, as decades passed, the waves of exiles or immigrants from Cuba revealed the class and racial systems still in place there, despite some of the gains from the Revolution. The first exiles in the 1960s were, for the most part, white, from wealthy backgrounds, from the oppressing/ruling class, with links to Europe. Later in the 1980s and further, it became visible who stayed in Cuba, or who could not leave and so, more people of Afro-Cuban background arrived in the US. How has your work addressed these nuances within Cuban displacements, relocations, migrations, and even assimilations in the case of the white, wealthy Cubans who can pass?

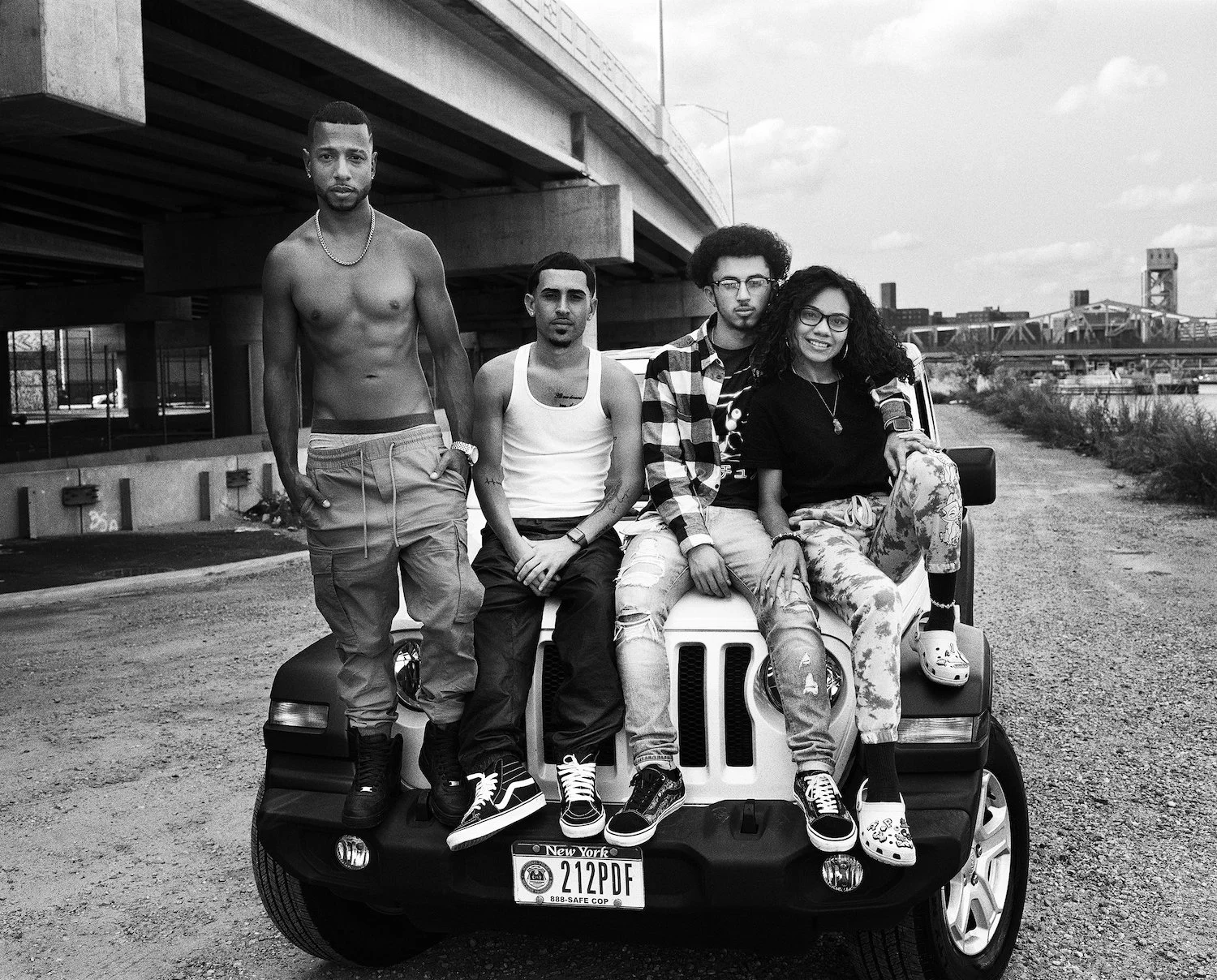

ADAS: In one of my projects, EntreVistas, a seven-channel video installation, I showed interviews of Cuban immigrants from different waves of migration during the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s together with a video of the oceanic border filmed from Cuba in Santa Fé beach, one of the places I used to go swimming as a child. In this work, I merged individual stories of exile, present within the history of Cuban diaspora into a shared experience. During this process, I learned there was more complexity in the stories of demographic categorizations than what I had read in books describing the Cuban immigrant experience. For example, I met people who built their wealth from hard work in Cuba to see it all taken away at the start of the Revolution. Stories like this one helped me see the “white, wealthy Cubans of the 1960s” in a different light. I also met people who grew up in homes with soil floors and went to sleep covering themselves with burlap to stay warm, who were able to study and become professionals under the Cuban Revolution; yet after critiquing the same system that offered opportunities they were oppressed and harassed until they had to leave their country.

After this project, I became a volunteer for the Cuban Cultural Center in New York City, in which I served for 10 years and was able to meet Cubans from all backgrounds and get a glimpse of their unique life stories.

NDEREOM: Thank you for this clarifying response about such complex histories.

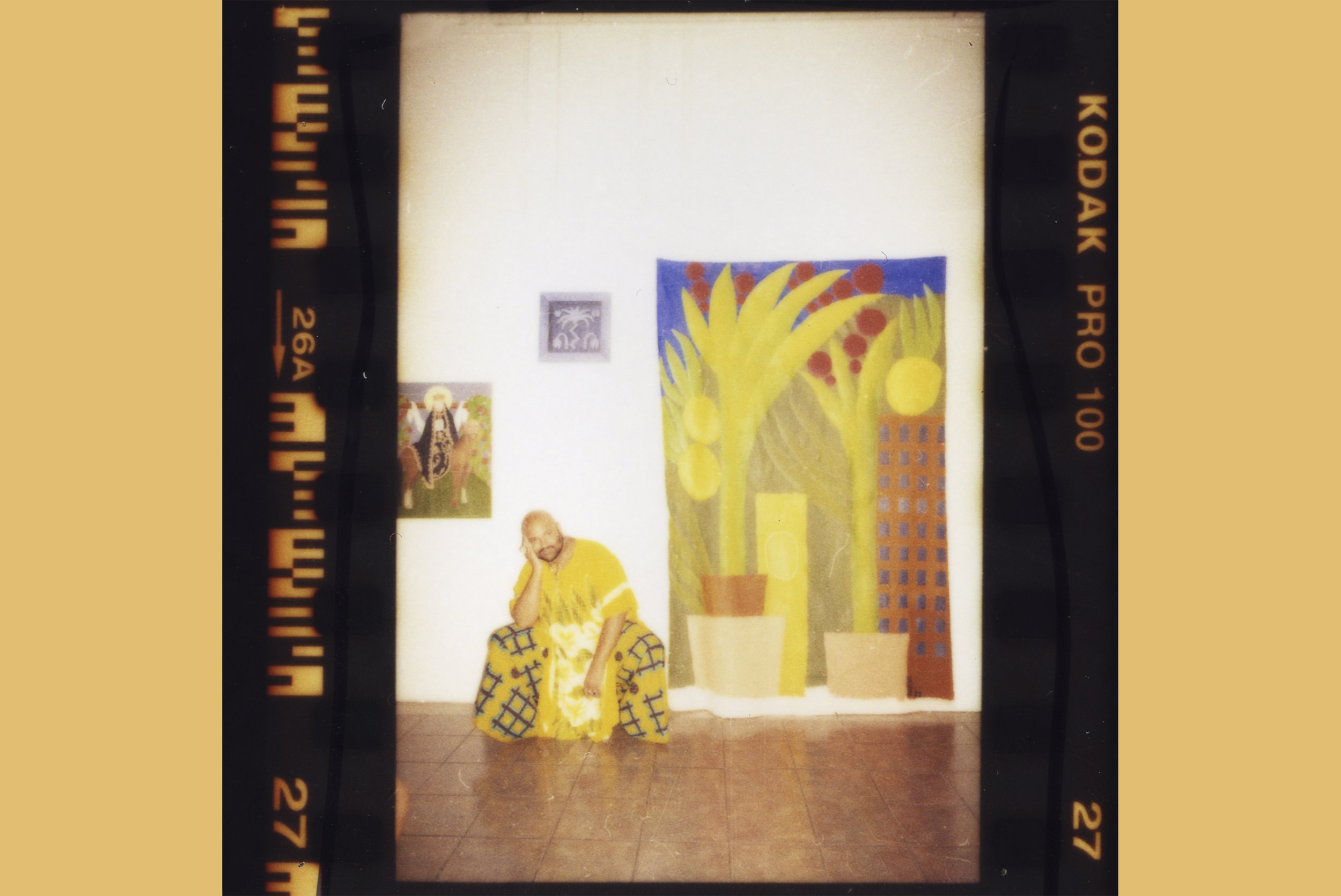

One point of interest for me in your creative sessions with Amy Pryor is how the two of you meet to be in each other’s company while drawing individually. However, eventually something happened and the work began to shift to the point where there is an exchange in your practices and it is as if you were channeling Amy’s creative flow and she was channeling yours. I will let you say more and perhaps offer details.

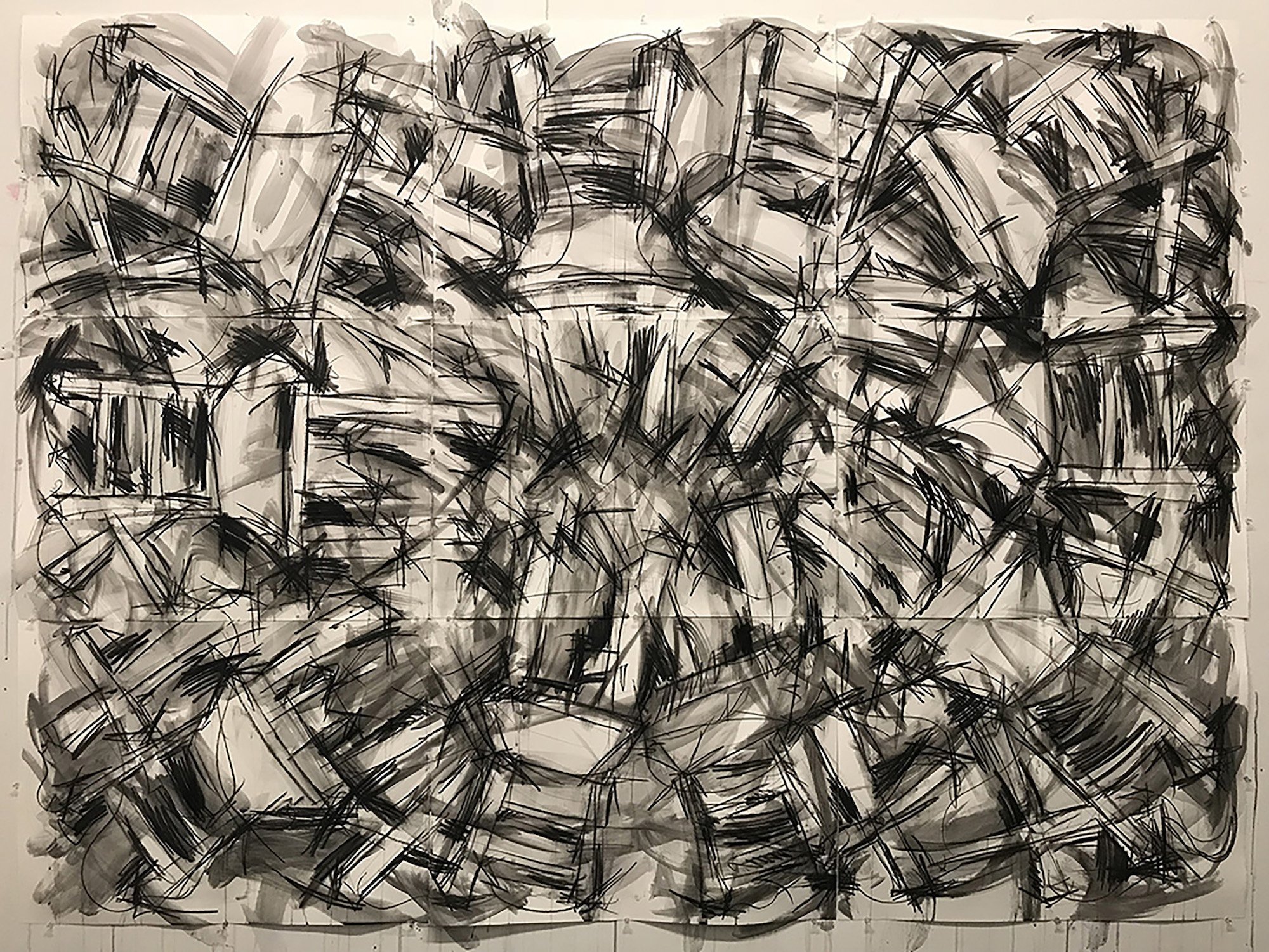

ADAS: The practice of Drawing Together / Dibujando juntas with Amy Pryor began during the Covid-19 pandemic. We are good friends and were neighbors in Riverdale, Bronx, before I moved to the Hudson Valley. The idea of drawing together emerged naturally and sharing a creative space while drawing was a conscious effort to create joy and deepening our friendship. Nicolás, I also see how this channeling of each other’s sensibilities and creative flow is evident in our drawings.

I met artist Amy Pryor at Two Palms over 20 years ago, a print publisher founded by David Lasry in New York City in which we both worked as master printers, collaborating with contemporary artists. One of my first projects was to assist Amy in the creation of large-scale language monotypes by Mel Bochner (1940–2025). I learned so much by observing Amy work with color. When Amy mixed and paired colors together, I remember thinking how unpredictable her color choices were, and she often surprised me in the way she perceived colors. With time, we became comfortable working in each other’s presence, mixing colors and placing them on the printing matrixes became an intuitive process. We were responding to each other’s color choices while respecting and staying within the color palette/vision of the artist we were assisting.

Amy and I work with color and abstraction in our individual practices. We have explored our connection to nature using colors from direct observation. Also, I’m personally interested in the lingering sensorial impressions of color while observing natural phenomena and the emotional and spiritual effect it has on the individual’s internal landscape. Amy and I are showing this work in an upcoming two-person exhibition at the Bronx Art Space in 2026.

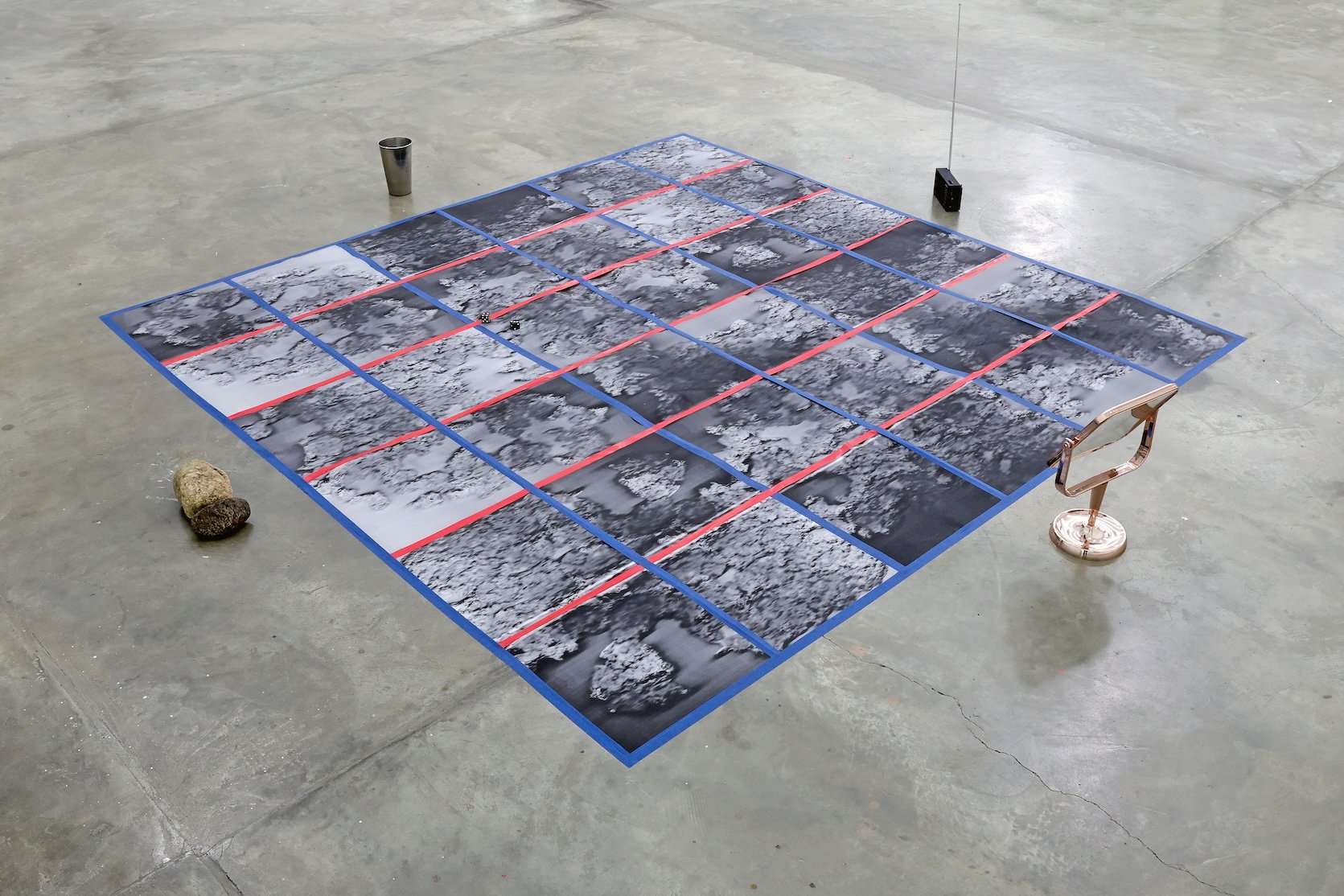

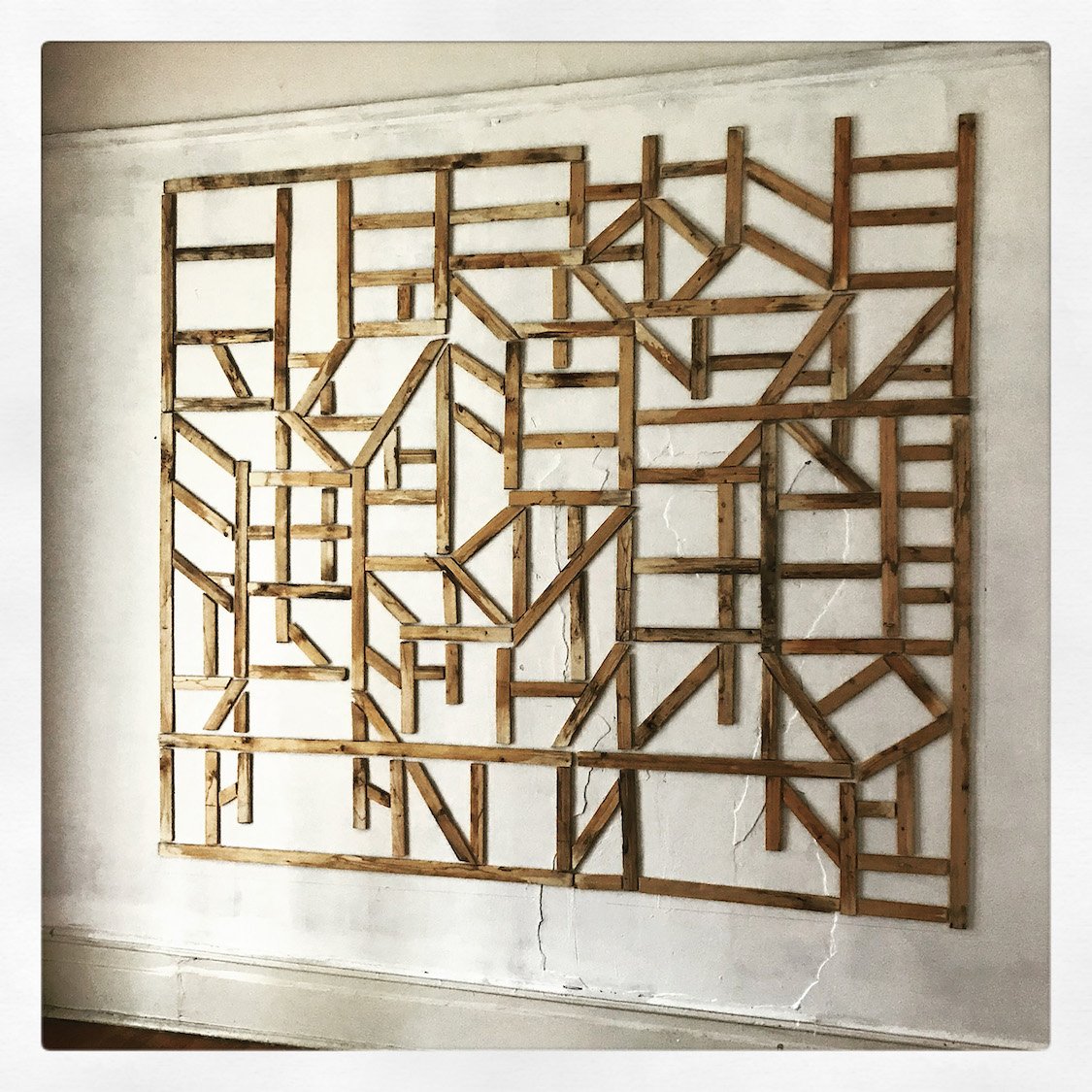

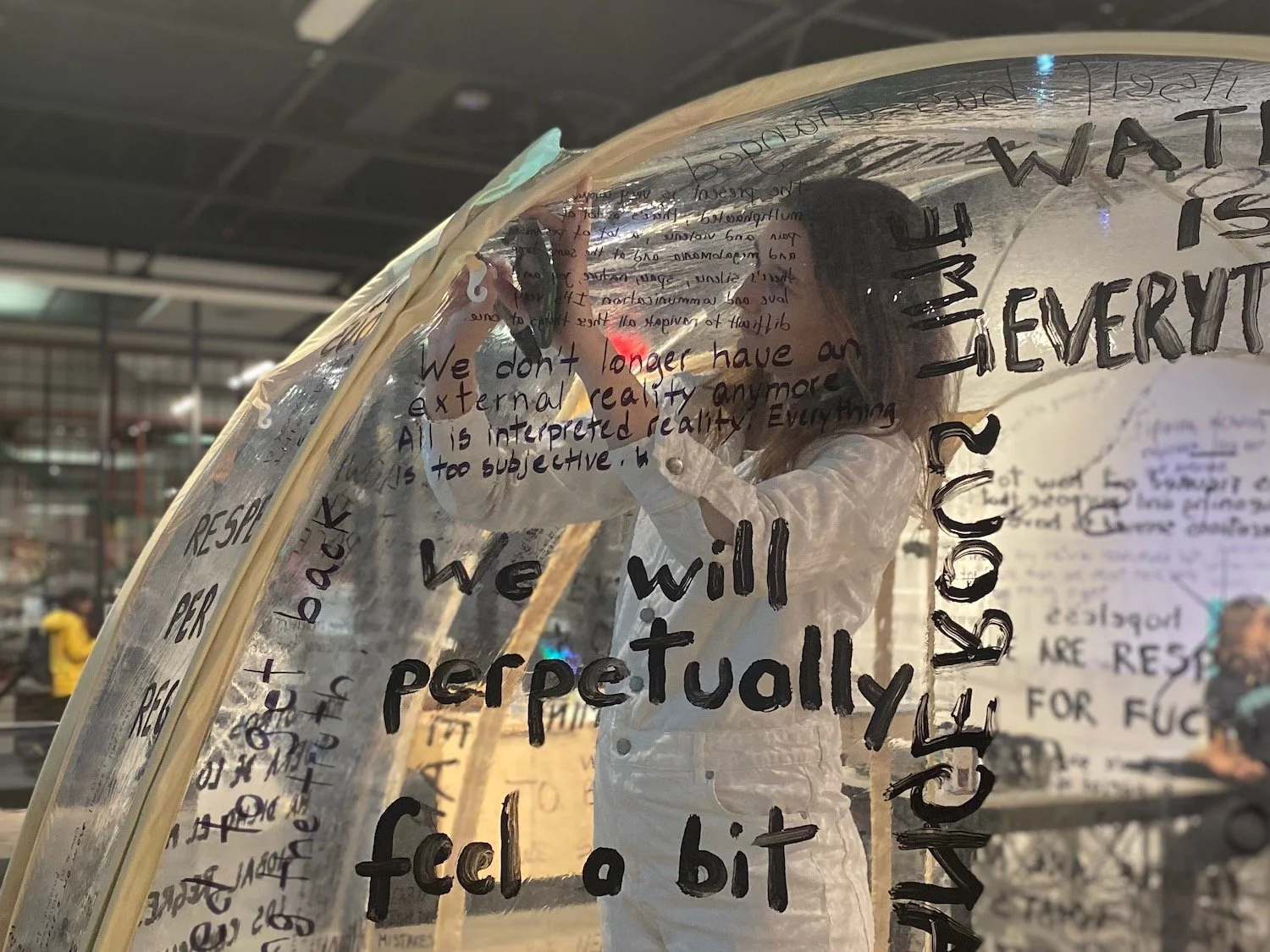

NDEREOM: Rather than ask you a question, I will open the space for you to converse about Water Lines, your collaboration with Andrea Frank.

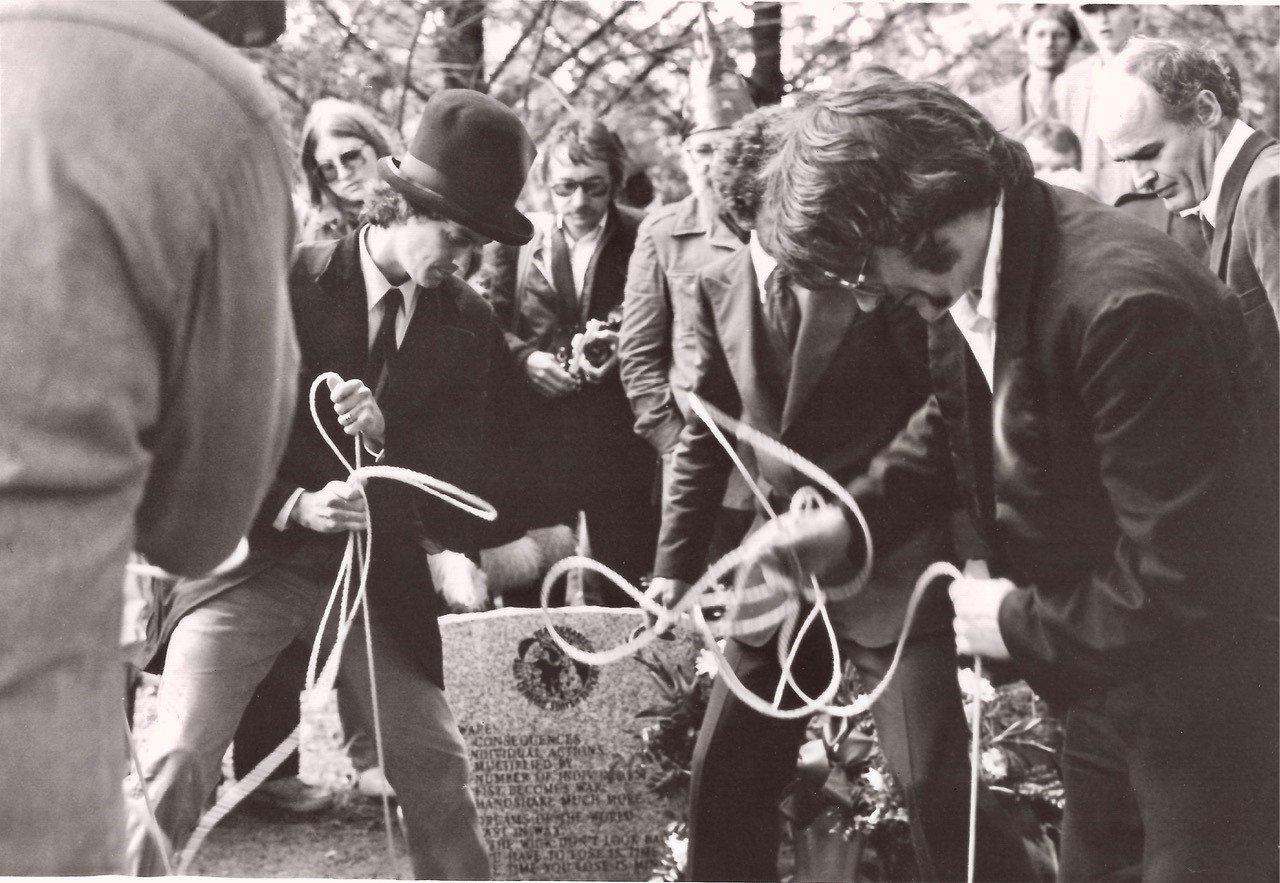

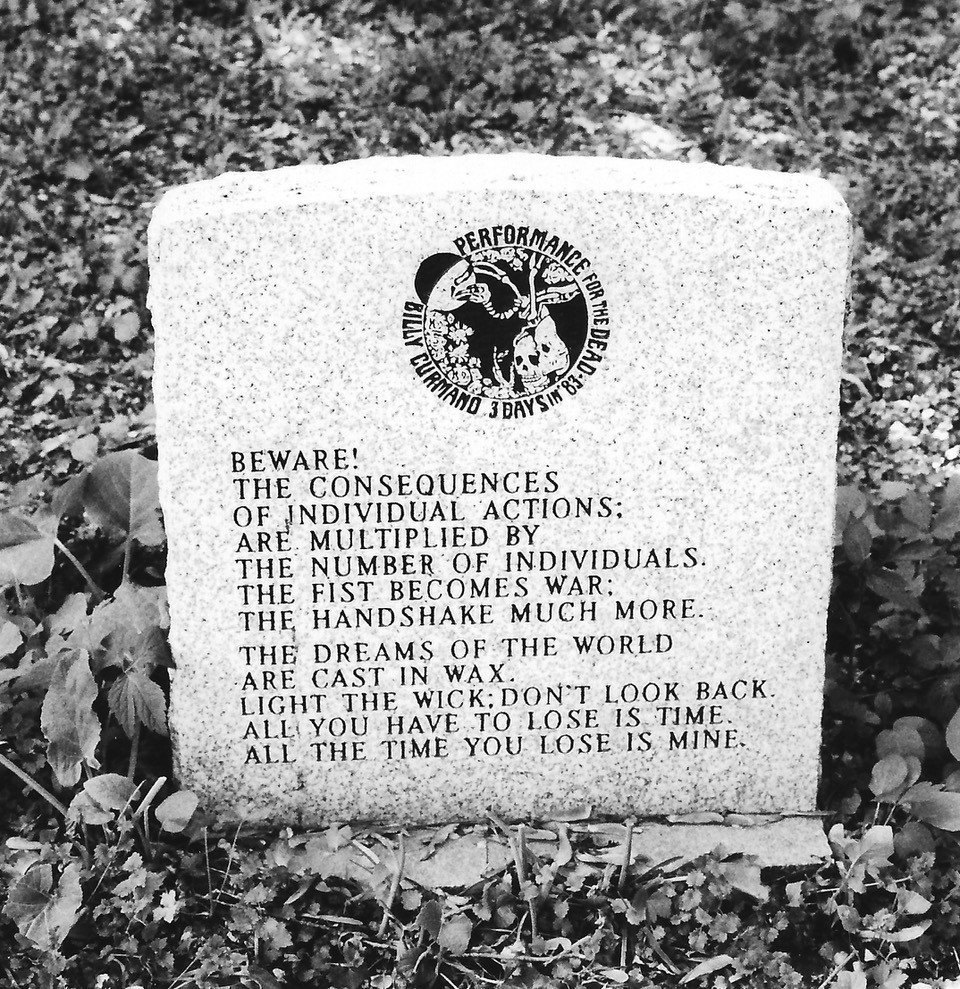

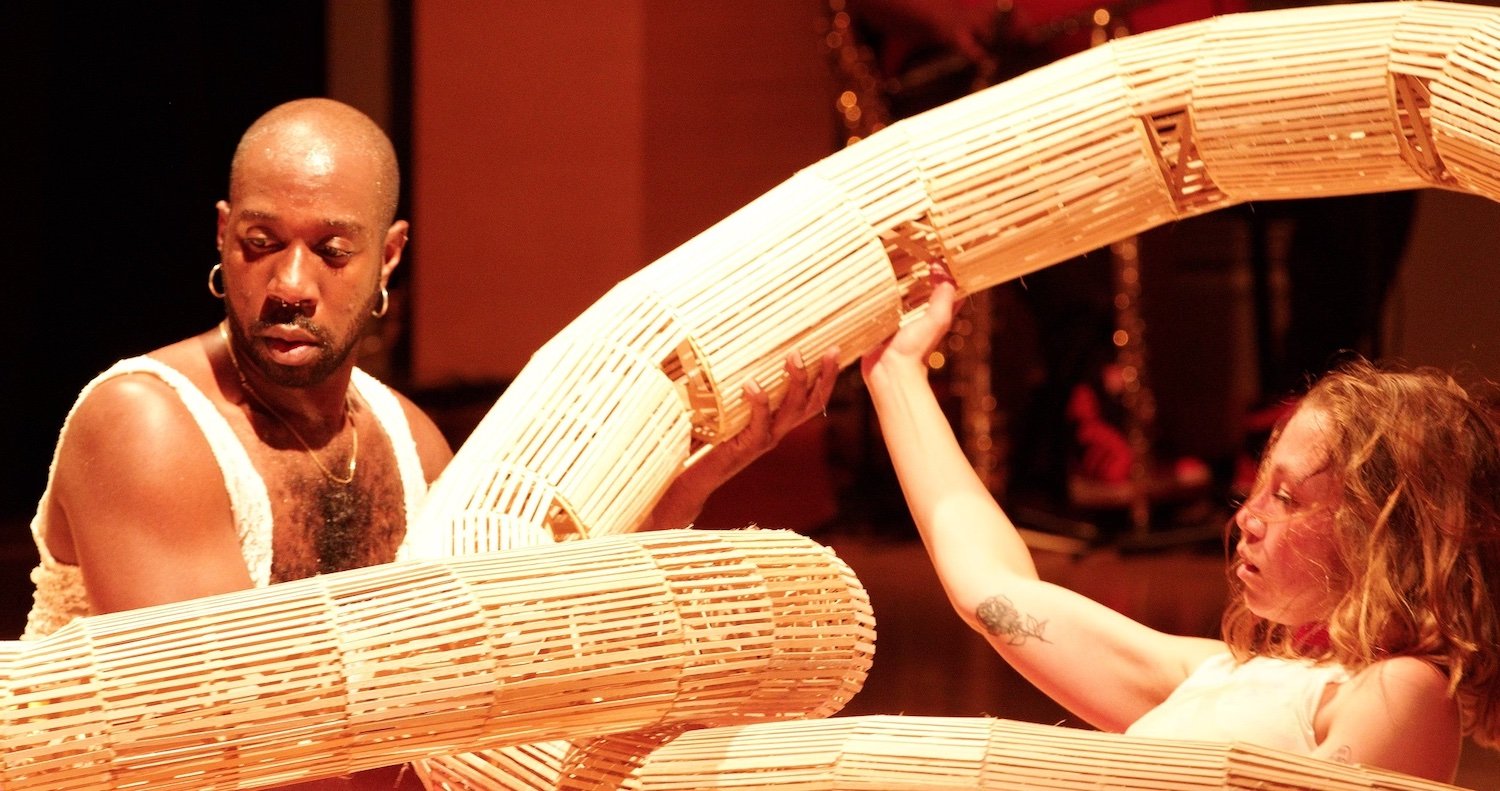

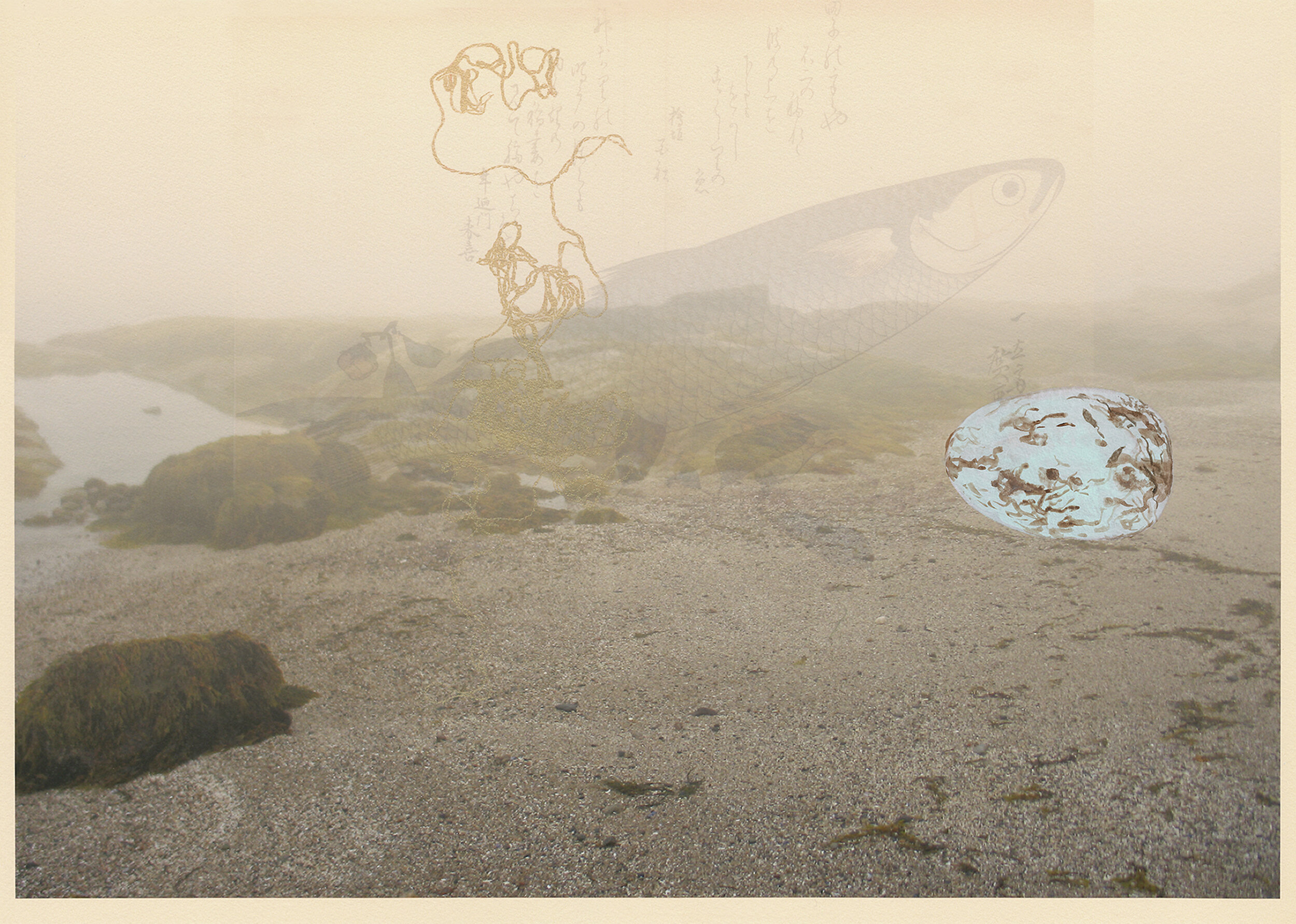

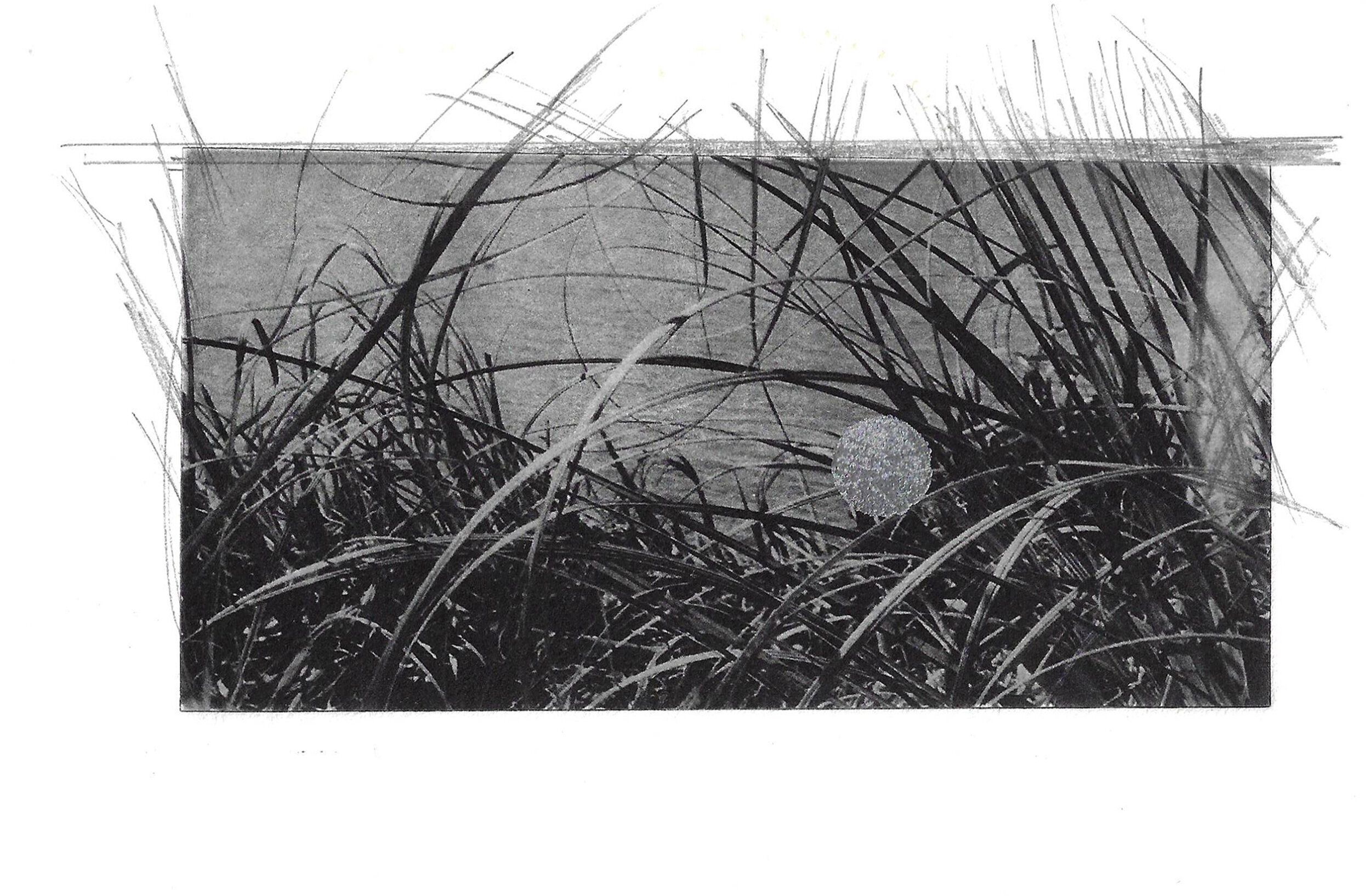

ADAS: My collaboration with Andrea Frank began in 2022 as we were getting to know each other as colleagues at SUNY New Paltz and after I accepted a teaching position at the same university. When I moved to the Hudson Valley from the Bronx, Andrea began sharing with me her favorite spots to walk and swim at the Mohonk Preserve and the Minnewaska State Park Preserve. In the summer of 2023, we brought wool and various types of strings to Peters Kill Creek and spent an afternoon feeding the string into the creek and observing the interaction of the string with the water’s current. We returned to the same location and other neighboring bodies of water to swim and continue making string line drawing. In the fall of 2023, we invited students and friends to join us in a drawing action as we wanted to share the experience of drawing in collaboration with water.

Our intention was to remain present in our bodies and learn from the water. We are continuing this process, visiting local bodies of water including the Wallkill River, Rondout Creek, Coxing Creek, Black Creek, Esopus Creek, Peters Kill Creek and the Hudson River. We also went to the New Paltz water plant to learn more about the local water treatment facility and understand its infrastructure.

In the studio, we are working with abaca fibers and wire to translate these drawings into watermarks and make a document as these drawing actions are ephemeral. There is so much to learn from water, we can’t survive without it…water makes space for endless and simultaneous interactions in its surroundings. Each interaction with stones, the air, rain, our bodies and other natural phenomena can teach us about flowing with life’s energy. By observing how water flows we can understand resilience, being in relationship with others, lean into tensions, explore resistance, engage in play and create joy. Other research for this project includes learning from waterkeepers around the world, their embodied knowledge of water and related stories.

NDEREOM: Is there anything that you would like to bring to this conversation?

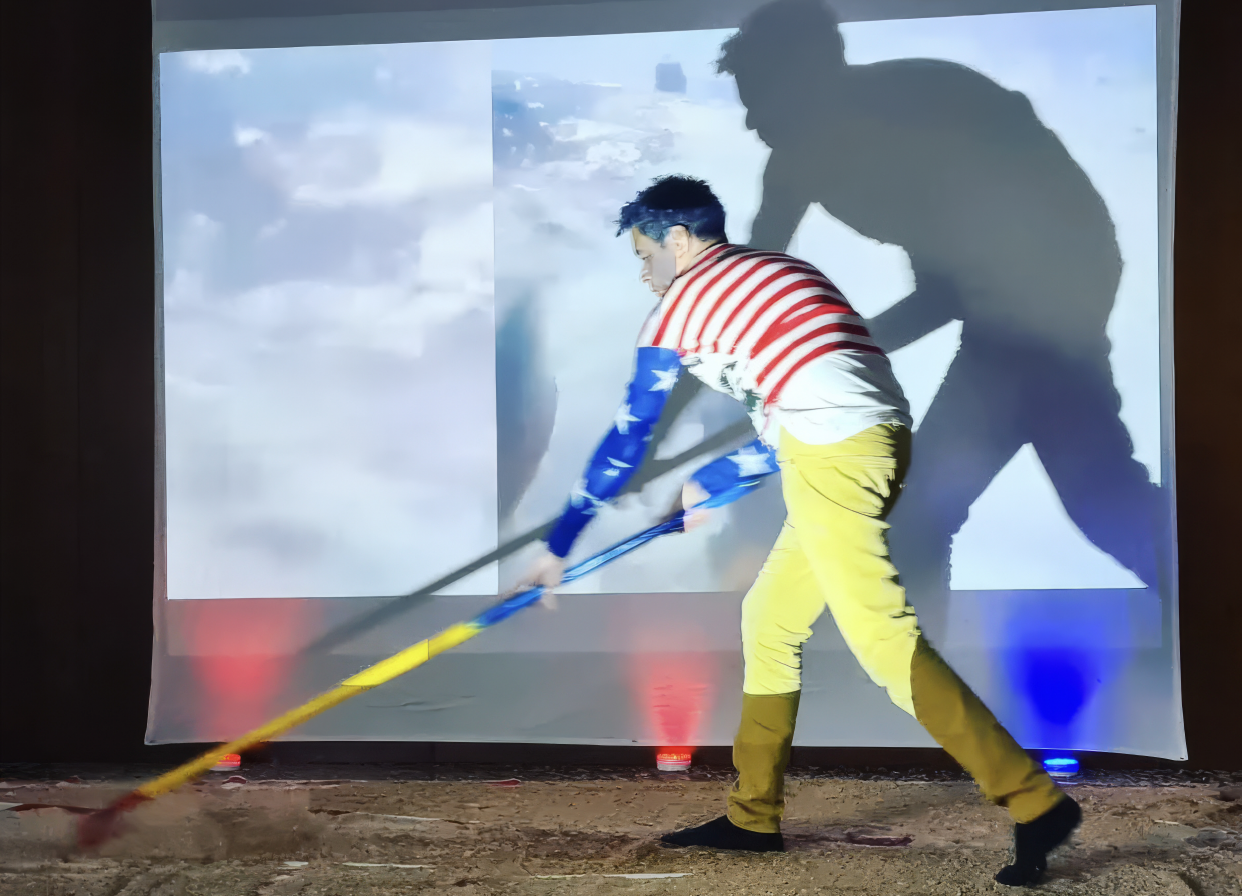

ADAS: I have had the opportunity to read more about your writings and artistic work through the projects, offerings and conversations in your site. It has been such a humbling and an educational experience for me to learn about your projects. I have always been fascinated with artists that work with their bodies… I think it’s rooted in my love of dance. I have a few questions I would like to ask you.

What is it like as a performance artist to have others interact with your body? I’m thinking here of the work Hope, your collaboration with Linda Mary Montano. How do you negotiate your own vulnerabilities when encountering the vulnerabilities of the people you interact with?

NDEREOM: That is such a great question. I wish Linda would be right here to answer this together with me, and maybe Linda will send a response that we can include here. She is a friend, teacher and mentor to me. I come from a place where most people are quite comfortable with our bodies, and I would not like to essentialize a region, country or culture. As a Caribeño, I continue to be culture-schocked about dealing with the body in US-Anglo cultures. To give you an example, when I moved to New York City, I would greet everyone I met with a hug and a kiss on the cheek until I saw people’s bodies freeze. I was born in a place where, generally speaking, people want to be seen, noticed, hugged, and where proximity of that kind is usually not feared. As for HOPE, the three-day performance in the Bronx with Linda Mary Montano, we had many different experiences with people interacting with our bodies. I reacall one where a group of young people wanted to write on our clothing and we were surrounded by a growing group. This felt a bit overwhelming. In an other occasion, a person drew on our clothing while almost crying. Her touch really touched me and Linda think.

ADAS: Can you talk about your inspiration to use dance, music and unexpected ways of moving in proximity to a chair in your work Sitting and Moving with what Arises?

NDEREOM: I was born in a culture where, if one does not dance, one is in great trouble. I know that I am exaggerating and in the Dominican Republic almost all revolves around music and dancing. I never understood how people could actually listen to music. Where I come from music is a force to move with, but not to sit and listen to. Sitting and Moving with what Arises was commissioned by Artists Relief during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The practices in the video come from different healing modalities, cultures and places, including Breath-Body-Mind. The Music is from the Underground Drummers in the Bronx. I am not sure I am answering your question, and I learned to dance with chairs with Anna Halprin.

ADAS: Can you talk about the role of humor in your work? Also, I’m curious to learn about your favorite color as well as your favorite fruit if you can share.

NDEREOM: My favorite colors are bright pink and Carmelite brown, like the monks and nuns. These were the colors of my schooll uniform while going to Catholic primary, intermediate and high school at Colegio Santa Ana, Santiago, Dominican Republic. I also mentioned before that I love bright colors. I am a child of the Caribbean who does hesitate wearing a pair of canary- yellow pants, a parrot-green shirt and orange shoes. Humor comes as well from my upbringing. I have the luck of having a family that does not take life seriously, and I am saying this in a figurative way. We learned to laugh with each other and at each other. I learned to make work and performance where I made fun at myself even when the subjects were dire and heavy. I miss this in the most the performance art that I see now, which is rather didactic for me. As a child, I grew up watching the most out there comedians on local Dominican TV. With this said, I do not condone sarcasm or humor that harms others. To me, that is not humor, but a corruption of it and of good, healthy laugher.

NDEREOM: Thank you so much for saying yes to taking with me. I am grateful for getting an insight into your personal story in regard to the Caribbean, a place I adore, as well as into how this experience has been manifesting for you through bookmaking in such conceptual ways. Please keep me posted on all you do.

ADAS: I’m also very grateful for this opportunity, thank you for reaching out and showing interest in my life and work and please keep me posted on all you do as well. I hope we can work together in some capacity in the near future.