Devin Osorio

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles: Blanka Amezkua introduced us while I was working at Hispanic Society on a pilgrimage dealing with La Virgen de la Altagracia, the protectress of Dominicans and, to some, of the whole Island. When we met, we discussed mothers as they pertain to our lives. Devin, you mentioned Washington Heights as the place where you were born.

Devin Osorio: ¡Hola mi amor! Yes, were introduced to each other by Blanka who is someone that I find deeply inspiring in so many ways. The conversation you and I shared when we first met was so interesting because it became deeply intimate and I felt comfortable enough to be vulnerable with you within the first few minutes all whilst talking in a very public space with raucous activity happening behind us ¡jajá! I remember leaving our conversation feeling as though I went to church and had some homework to do. At the end of our conversation, you challenged me to return to the block that I grew up in and provide my mother (R.I.P. María Lucía Checo de Osorio) an offering – a piece of chocolate that you gifted me. I never had the chance to fill you in on that deeply moving and monumental experience. I didn’t realize how terrified I was of my block and encountering the people that I grew up with until that day. The walk from our meeting space on 155-156th Streets and Broadway to 175th Street and St. Nicholas was fairly mundane – but once I turned right onto the block to approach the building I began to hyperventilate and became extremely anxious. I began to feel watched and judged whilst the block was mostly empty. It felt as though people were hiding in their apartments glaring down at me from their windows, all disgusted with the faggot I’d become. Luckily the door of the building was broken and could not lock itself. I quickly walked into the entrance of the building, dropped the chocolate in the corner of the entryway, and walked out as quickly as possible towards the A train three avenues away. I hadn’t felt panic to that degree in such a long time. That visit motivated me to create a collection of paintings that attempted to understand those feelings and where they stem from. It was the first time in my life that I tried to explicitly call out my “monsters” and attempt to sit with them.

NDEREO: I am getting goose bumps. I was in Washington Heights in the early 1990s and that was quite a place in the City’s imaginary. People who lived below 96th Street or in “safe” areas of New York would not visit me. Washington Heights then was what the Bronx continues to be now for many New Yorkers and beyond, a place to fear. To me, it is all about race and the Other.

DO: “The City’s imaginary” – I love that. New York City is such a fantasy according to which perspective one is studying it. Well, the fear that is held currently about the Bronx, and due to gentrification, has been slowly dissipating about the Heights and parts of Harlem as of late, has a lot to do with race and othering but also with class – specifically one’s image of what is New York City and which areas are deemed worthy of being included in its definition. Outsiders view the ratchet, banjee, and ghetto as something to emulate from a distance but not considered worthy enough to get to know up close and personal. The fact that uptown is made up of mostly residential neighborhoods filled with underserved people of color with select pockets of commerce and nightlife has made those neighborhoods unfriendly for tourism/visitation. For a long time, there was an annoying view that uptown had nothing to offer other than buy drugs and/or get shot.

Whenever I think of this fear of the uptown, I am reminded so much of high school. I went to New Design HS in the LES which was about 45 minutes traveling each way on the train. I remember realizing in and around my Junior year that none of my friends would come up to see me. Any time we shared had to be done “downtown,” in spaces that were a 20-minute walk for them but a 45-minute to 1.5 hr commute on the train for me. I would get aggravated easily jaja, at times boycotting the train and refusing to see them over the weekends if they did not come up. Yet I understood them. I understood the lack of desire to commute a long way to a neighborhood that due to redlining, lack of employment opportunities and financial growth, struggles with assimilation due to the struggles of immigration, and other systemically racist actions was forced to become intimidating and not provide much incentive for visits. I learned to see that there was a delineation between actions that can happen uptown vs. downtown – a matter that has always fascinated me.

As a child, I was not able to take the train alone and my parents had no reason to take me either. I had not gone lower than 125th Street until the age of about 13. Downtown was called “La Cuarentay Dos,” throughout my childhood because my parents worked near Times Square and my aunt Almania loved to shop for bargains in that area. La Cuarentay Dos was a magical place with glimmering lights, cobblestone streets, and cherry blossom trees that only adults and children in movies had access to. It was a place where celebrities and fabulous people spent their days and only the most worthy could share that space with them. La Cuarentay Dos was a fantasy/imagination. This fantasy stemmed from many sources. With most jobs being offered to immigrants being held downtown by large-scale chains and large corporations, it’s made it so that some individuals living in the outskirts must travel for income. They must leave their neighborhoods to succeed – psychologically making their neighborhood a space that one must get out of to thrive. The only way to go from uptown was down.

The perspective that flourishing only occurs with escaping permeated beyond paying the rent but included a sense of safety for queer people. I personally found downtown to be more than just exciting for its newness but a space of protection, allowing me the space for self-actualization within its air of anonymity. Existing within a sea of individuals that did not know me, granted me the permission I needed to fearlessly be my fully effeminate self. I was not being surveilled downtown in the ways I was uptown. Yes, I could be attacked – I had little control over that – but what this newness gave me was the agency to be whomever I wanted without a past to compare to. I could be the person that was never afraid of being jumped by people I grew up with for being queer, I could be the person who could be romantic with the individuals I desired. No longer did I have to hold my tongue or constrain my gestures in order to avoid abandonment. Within a sea of strangers, I was able to put my troubled past in a box and dig it underground until I decided to resurface it.

I vividly remember that when I began to express my queerness through dress I only felt comfortable doing so if I made my way downtown. Passing 125th Street on the A or 1 train was a moment of unfurrowing. My shell would slowly open and my sense of danger would slowly dissipate. Yet this exciting reality came with a price. I began to resent home and associated Washington Heights and even Dominicanness with fear and heartbreak. For many years I did all I could to disassociate; using any opportunity to escape and take space in anyone else's. I think back to that time and feel deflated because I should have fought for my comfort, I deserved to feel whole in the spaces that I call home. Funny enough, my pride for my neighborhood came much later once in Savannah, Georgia. With all this said, I realize that present-day – gentrified Washington Heights is very different from the one I grew up in. The Heights has become a household name for Dominicanness in NYC and we appear on Broadway and in movies that don’t centralize violence. Although explicitly gay bars in Washington Heights/Dyckman have closed (R.I.P. No Parking and Castro Bar), there is a thriving gay scene in Harlem. Extracting the displacement and the unjust price jumps in rent and survival, these changes are amazing because they provide employment, community, and safety for individuals uptown. It’s a shame though that those who survived the eras of uptown are not able to enjoy its fruit. People come uptown now, and it’s not only to buy dime bags but typically for hookah and pastelitos in Dyckman as well.

NDEREO: When I talk with my aunt we become nostalgic about the New York that has slipped out of our hands. 14thStreet was the locus with the crowded shops with Jesus’s wall pieces, suitcases and chamber pots for sale. In my opinion, Washington Heights is no more. I rarely go there and prefer to keep the memory of a time when I really felt the Island there. Now, there are more Dominicans in the Bronx than in Upper Manhattan and the cultural cohesiveness that took place in Washington Heights will never happen here in a whole borough. I see that I am not asking questions and I am okay with you responding to these thoughts in any way that feels true to you.

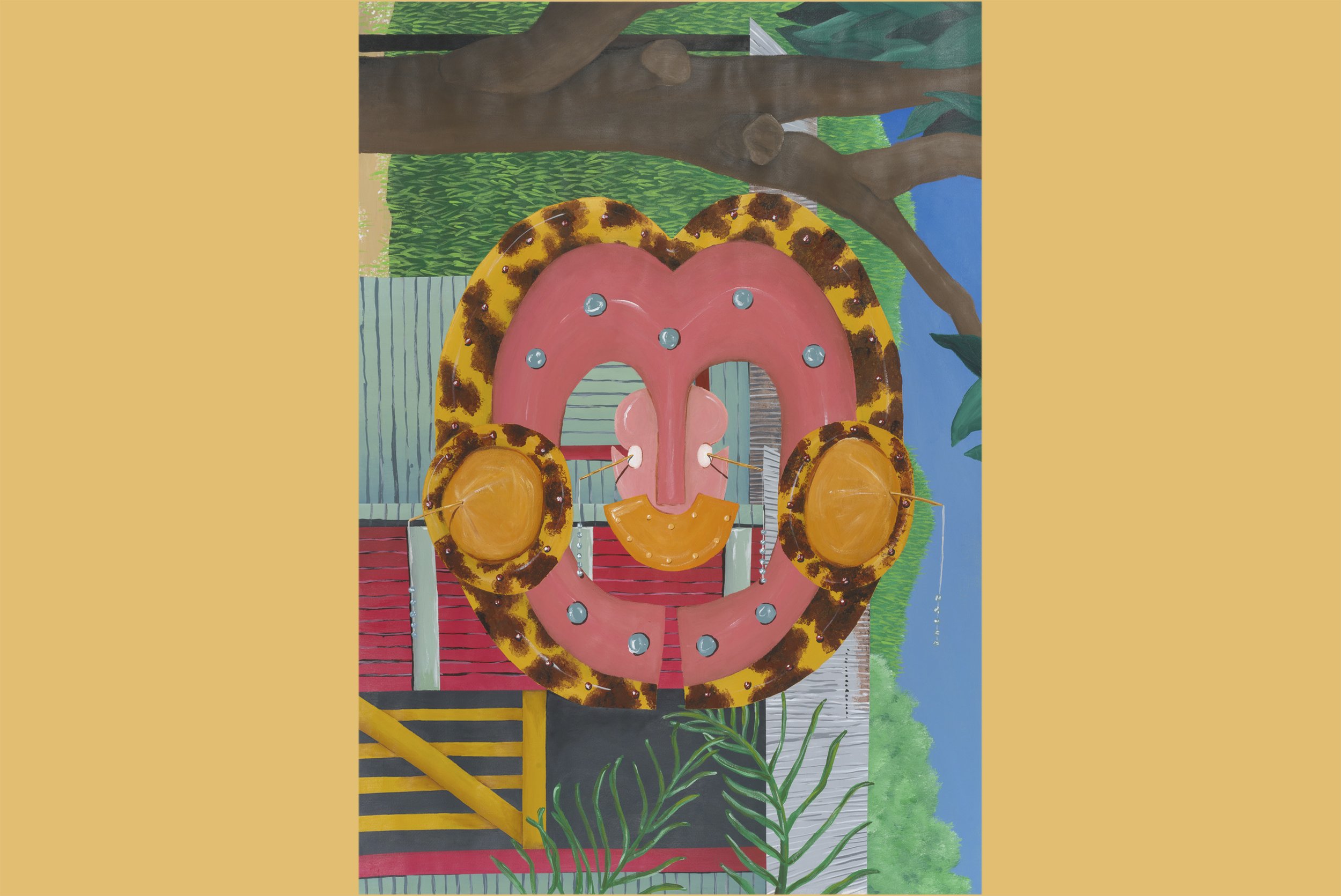

DO: ¡Jajaj! I’m loving the stream of consciousness that you are having with me! Ultimately I agree with you. The Heights that once was is gone and in its place is a commercially branded rendition. With the rise of Dominicanness being made cool in media and Dominican machismo being highlighted as both something to fear (the common concept that Dominican men are cheaters and Dominican women are BBL carrying loud mouths) and something to aspire to (Drake being posed as a Dominican with metros sexual clothing and that Dominicans have an innate street smartness). I feel as though media exposure and cultural relevance have encouraged people who have survived gentrification to swallow some degree of the commercial cool-aid. Although some family-owned businesses stick around such as La Casa Del Mofongo or El Tropical throughout the years, most businesses are gone, rebranded, or new ones have taken their place. No longer are they unimpressionable shops and restaurants with great products but are highly decorated catacombs of Dominican folklore and nostalgia. The carnival masks that were once only seen in select people's homes in the Heights are now seen on a shelf in almost every business alongside a tin mug and countless frames of Caribbean tourism paintings. The low-budget but major cultural impact of Washington Heights that once was is gone and in its place is a media-friendly backdrop that patrons can interact with and easily post online.

Through my disgruntled rant, I am reminded of an experience back in 2018 when I coerced my younger sisters, Arshley (16 y/o at that time) and April (12 y/o at that time), to go on a walk with me. We started our journey on 181st Street and Broadway–made our way down to 158th Street and Audubon, and back up again to Dyckman. Those poor things – I made them walk all of Washington Heights with me. As we did so we caught up on chisme and shared memories that we had individually had in the neighborhood. I was stunned to see so many empty commercial spaces and most of my childhood stomping ground vanishing. As we passed the first Target to open in the neighborhood, I complained about its placement and went on a rant about the negative effects of gentrification and how awful it is to see the past gone. My sisters rolled their eyes at me and in unison said, “I’d rather have it here than have to go all the way to the Bronx or downtown for a fucking Target.” At that moment I realized that it was easy for me as an outsider ( I moved from the Heights at 17 and spent minimal time in the neighborhood because my friends all lived in Brooklyn and I partied near their areas), to complain and want to hold onto a past that may not be beneficial for the locals that were still there and had no plans of leaving. For them, replacing one of the countless 99-cent stores or second-hand clothing stores that no longer serve modern needs with a large chain that benefits their lives was a blessing. Since then I’ve tried to be cognizant of what I fight so hard to hold onto. Is it fair to hold onto a romanticized past that has negative effects on the present? Am I creating an encapsulated monolith by gripping onto a past rather than allowing it to transform and breathe the air of change?

I miss the enclave that Washington Heights used to be – the stark contrast to the other neighborhoods in Manhattan, but I also remember the days in which I fantasized about leaving the neighborhood to become a club kid and allow myself to be an uninhibited, extraordinarily dressed, enigma. As a visual artist that aims to document the Dominican diaspora in Washington Heights, I’m constantly asking myself those questions to ensure that I’m not creating a false relic but instead celebrating my spaces and sensations of comfort and joy.

NDEREO: How has the Washington Heights experience influenced your creative concepts and aesthetics?

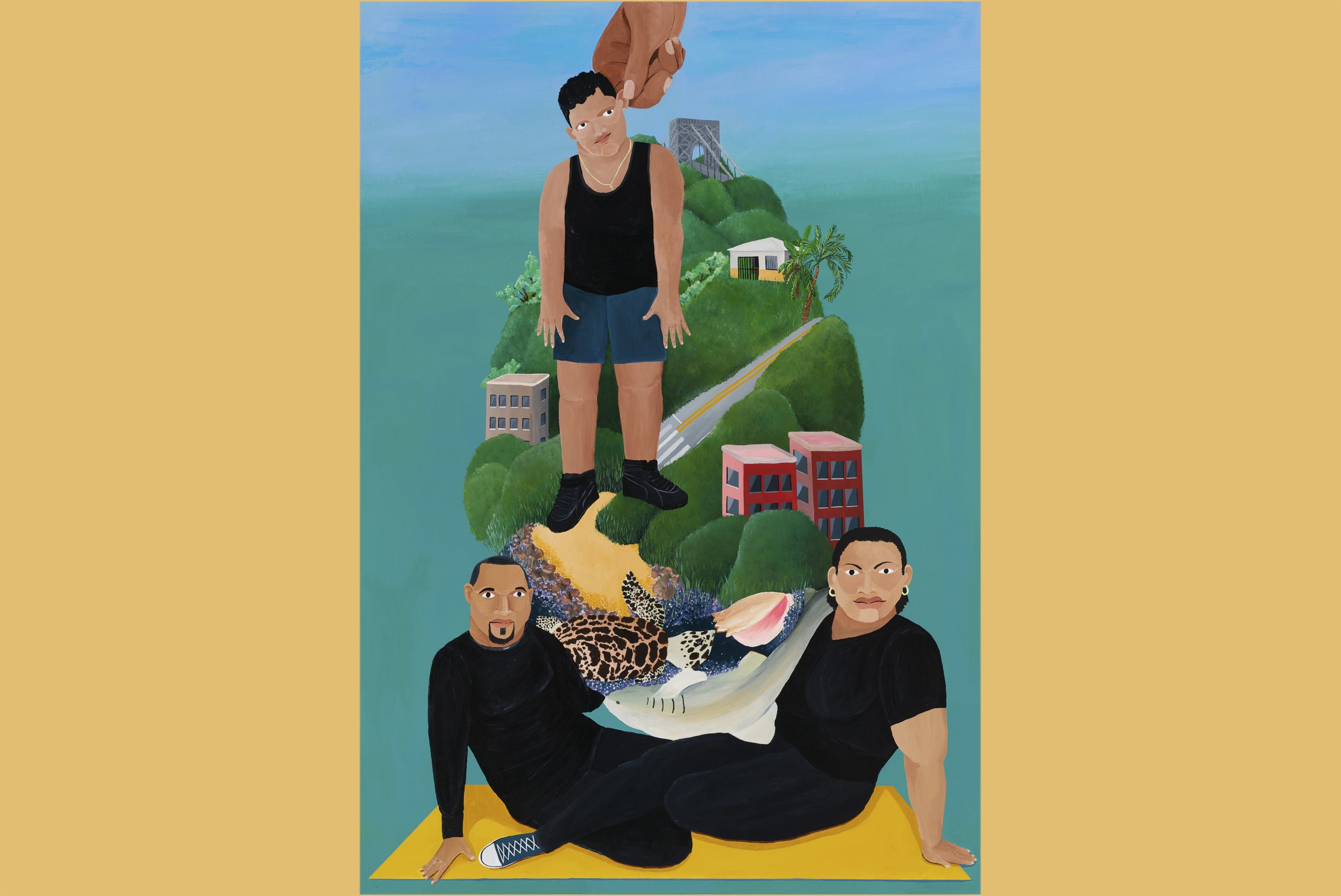

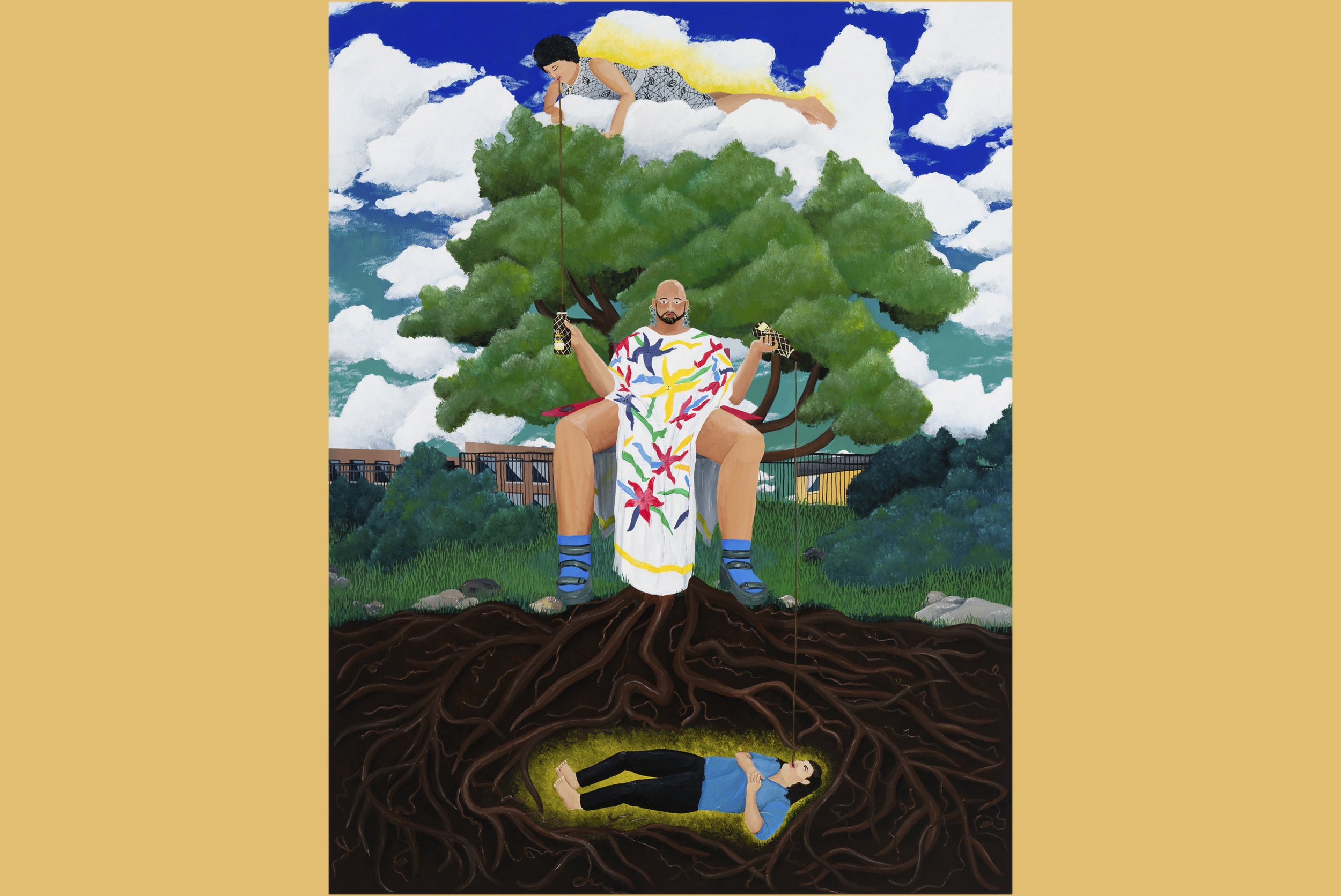

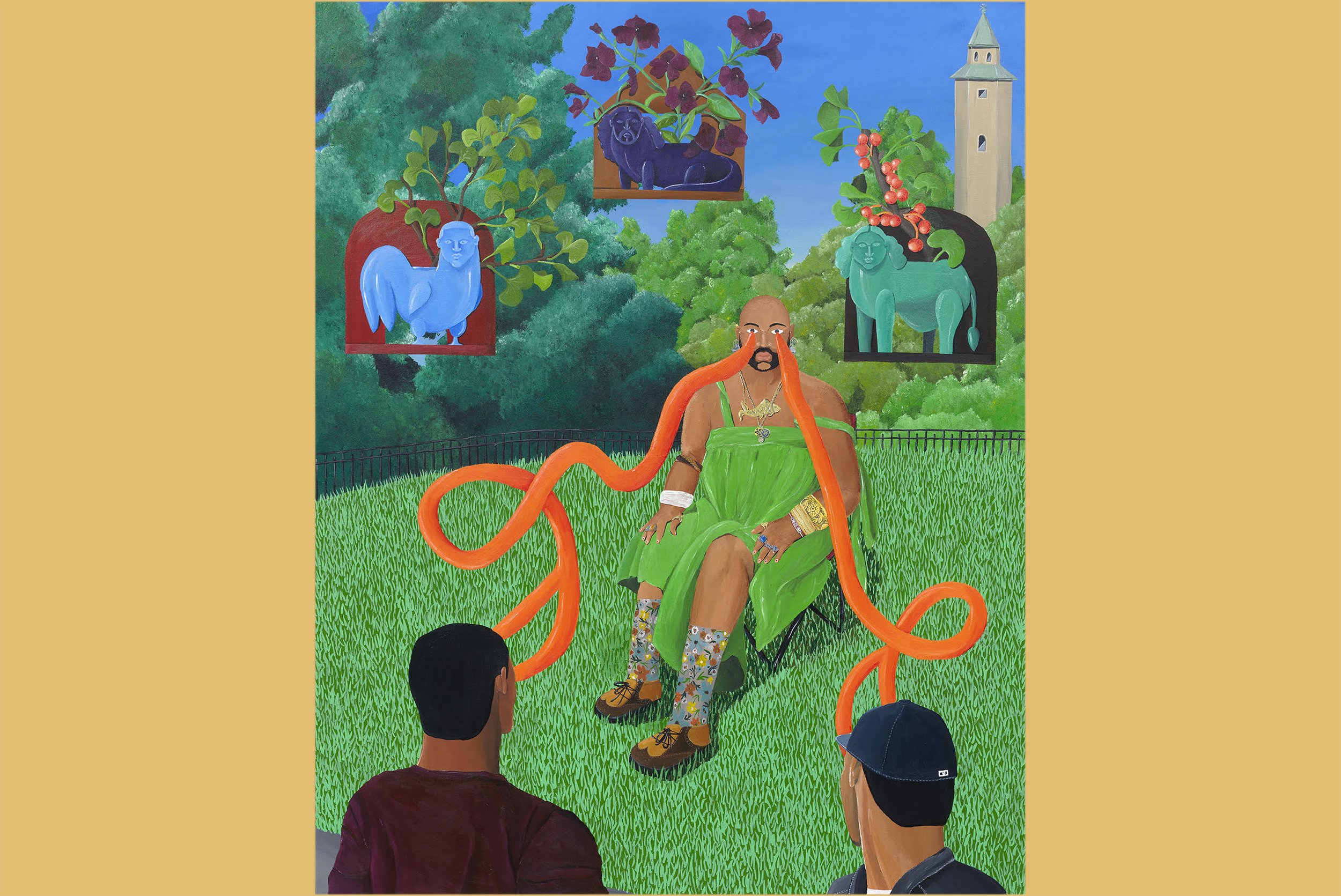

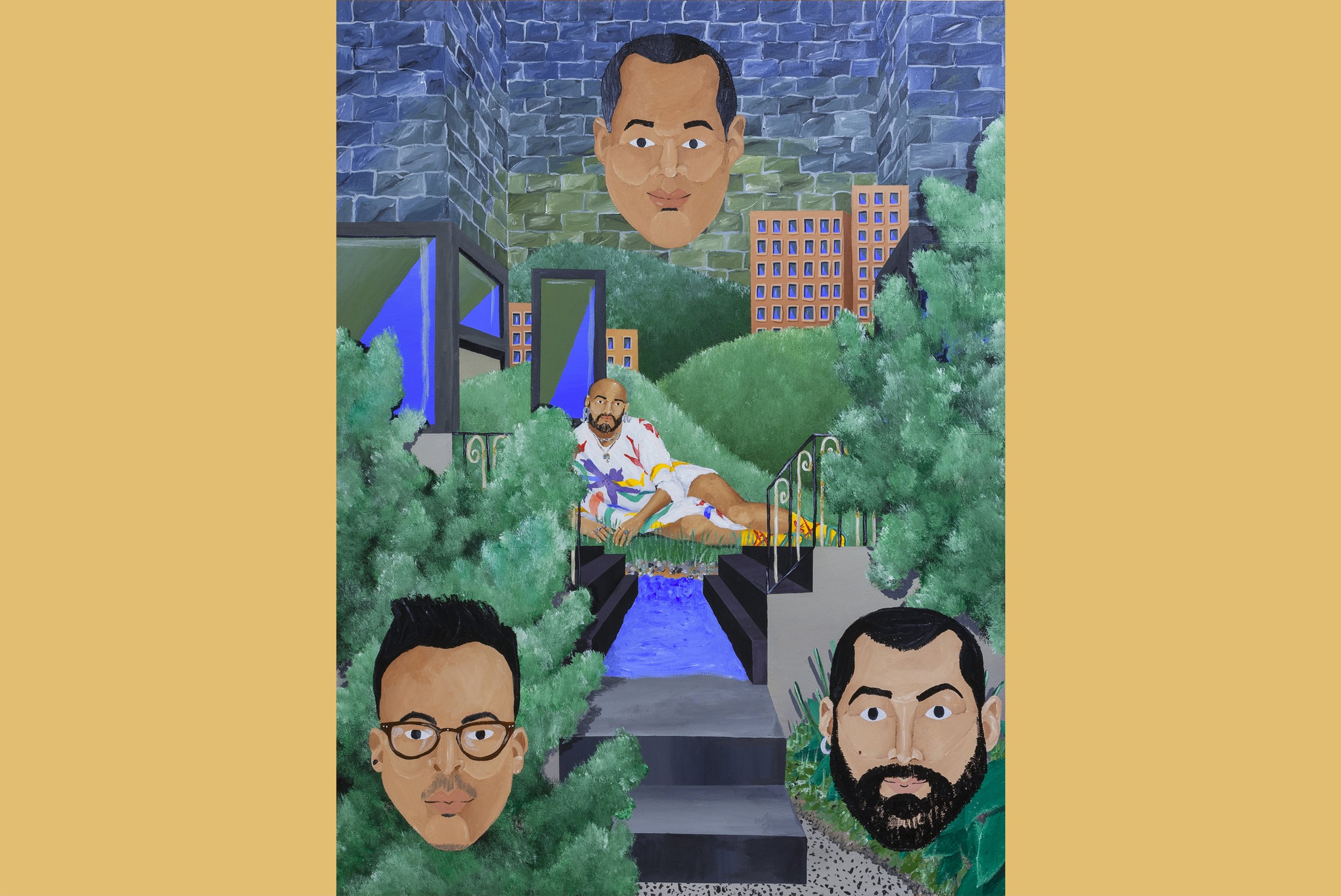

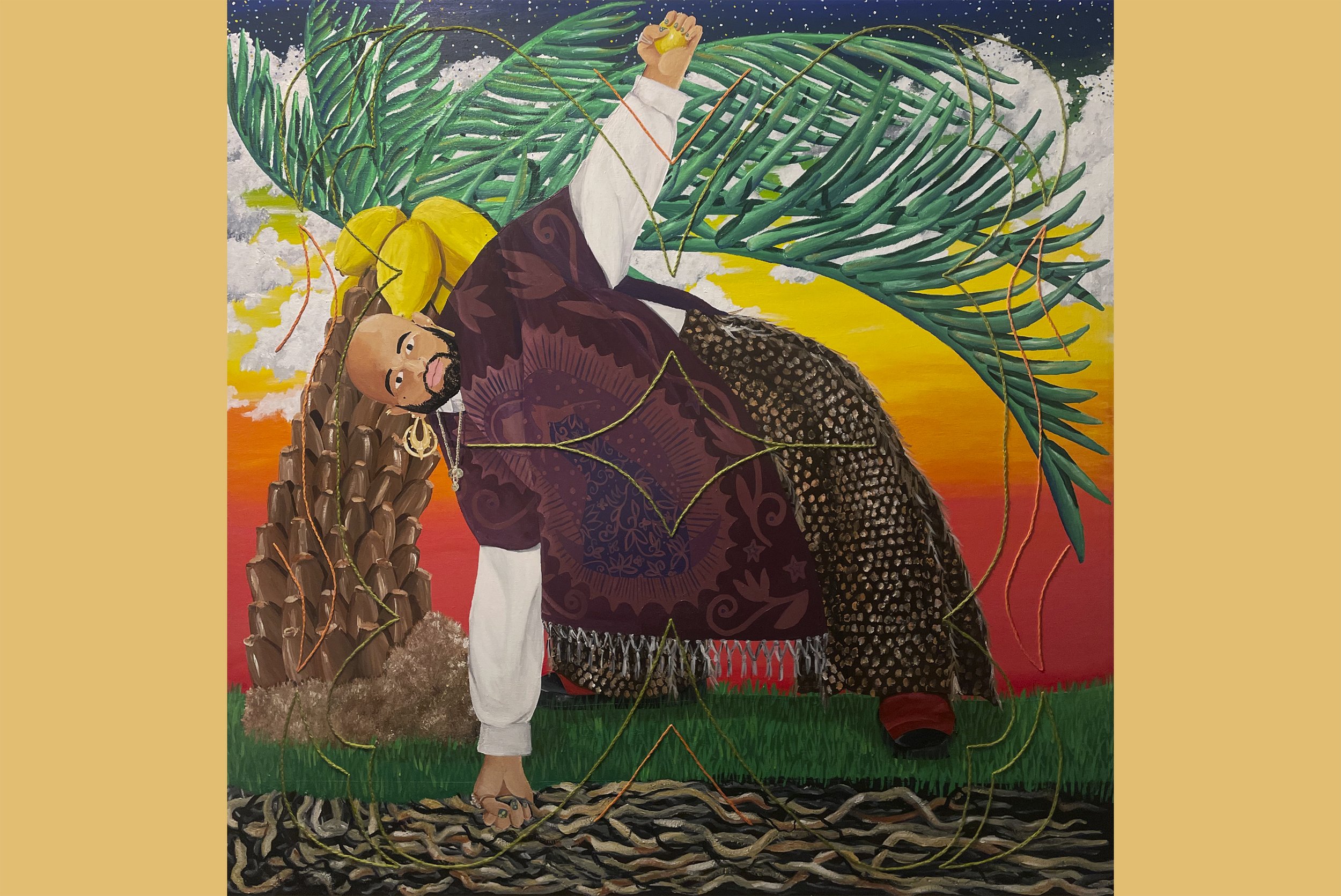

DO: In every way possible. I began to explore my lived experiences and my ideations of home during my final year of college. Before then I was creating “aimless” work that tended to settle for low hang inspirational fruit rather than forcing myself to dig deeper into myself and study my psychology. Once I began to do so, I realized the well of inspiration that I had completely ignored because I was too scared to notice my own emotions, my interior. After studying magical realism and learning how to integrate its guidelines and tools into my practice, I became aware of the fact that it’s easier for me to confront heavy emotions and large concepts with images and fables. I began to use my neighborhood, the people I share space with, my cultural background, and myself as caricatures. I can utilize all that I know to discuss themes and attempt to comprehend concepts that I am intrigued and deeply confused by. For example, using the evolution of the inhabitants of the neighborhood to discuss themes of regeneration and cyclicality. My personal traumas become tools that can be used for empathy or reaching euphoria/utopia. My clothing and the ways in which I express myself become physical manifestations of my psychology.

Most of my practice includes Washington Heights in one way or another, either in its physical representation or in depicting myself. I am the heights – it made me. Just like I am my mother, father, and siblings because they also made me.

NDEREO: At the moment, the aesthetics of Vodun are hip in the arts and many artists are embracing it. I am curious as to the level of understanding and responsibility involved in the works that I see. I do not practice Vodun and I grew up with this religion, among others, at home. At seven, I had an altar that I had built in my own bedroom in Santiago. I get uneasy when some of what I see in the arts is about the trappings of Vodun. Tell me about you.

DO: I absolutely agree with you, the aesthetics of Vodun and general spiritualism is becoming very hip in the zeitgeist at the moment. Every young person seems to have one finger touching the moon understanding its thoughts whilst another in the ground catching its vibrations. I say this as neither a positive nor a negative thing. I also wonder if those artists are respecting the practice and hope that they are taking the time to fully understand and intimately know the subject they’re depicting/reenacting. I find it beautiful that Afro-religions are being removed from taboo and being seen as approachable. Accepting our blackness includes accepting the spiritual practices that shaped our ancestors’ psyche.

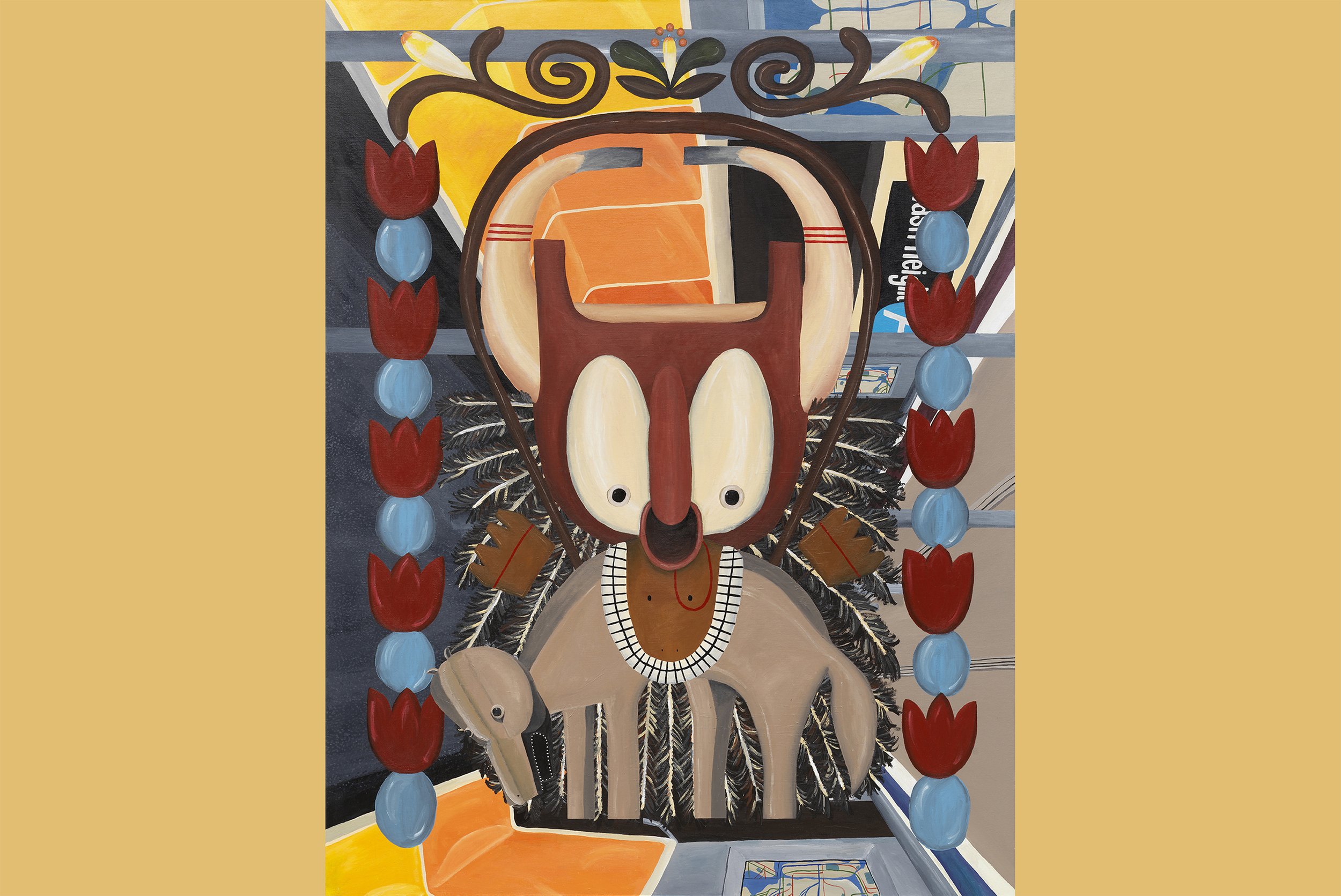

Similarly, I do not practice Vodun but I did grow up with family and adults that practiced Los Misterios, the Dominican rendition of Vodun. Although growing up I had no clue of their spiritual relevance, I remember small objects such as a small Oshun that my mother kept in our bathroom and an Eleguá that my aunt placed on the floor near the entrance of her apartment. Every child born into my family was first seen by the Santera who gifted them a blessed amulet to wear weeks after their birth before being baptized on their first birthday; both acts functioned as rights of passage. Due to Los Misterios being present in my life alongside crosses and other Catholic symbols, I began to view spiritual practices as acts of culture rather than devotion. Angels and Jesus Christ on the cross became elements of decoration rather than signals of allegiance. I also began to notice that the human experience loves to attach psychology to objects and create altars. Globally most spiritual practices utilize altars in one way or another and commit to a transactional exchange between the devotee, the talisman, and the divine. One could say that part of the human experience is not only to understand that which we cannot through the creation of mythologies and fantasies that we become devoted to but it’s also part of the human experience to collect that which is physical in our surroundings and place them into a caste system of divine value. Offering them as we see fit.

This personification of an object is one that I’ve always loved. As a child, I would create stories for the objects in my life. Wondering how the TV felt if it was not turned on all day or if the bed rested throughout the day when I was not sleeping on it. Practicing animism, more specifically, assigning interactions and tasks to all objects has always led me to question the value that we place on specific ones. Attempting to understand at which point an object changes from being mundane to being totemic. In many ways, this thought process stems from Los Misterios and altar building: the ways in which a saint's personality is represented according to the offerings being left for them by the devotee. Altars function as physical manifestations of the divine whilst the offerings are symbolic of their psychology. I’ve begun to use this formula of altar building as an attempt to represent earthly individuals and more excitingly, concepts. Deciphering which collection of objects best represents machismo, devoutness, and wholeness. Within my work, potted plants are symbolic of controlled existences while plants in the earth represent human inward reflection and connectivity. Vessels are societal constructs and objects that produce light such as candles, incense, and lamps representing spirit.

Personally, I pray every night to God, the Virgin Mary, Anaisa Pye, and Santa Marta la Dominadora. Showing gratitude to the four of them equally for the blessings in my life and placing faith in all four to protect and guide me daily. I am not a Santero nor a devout Catholic/Christian. I do not have an altar in my home that is meant for spiritual practice. Yet I do have images of my favorite divine characters throughout my living spaces and peppered into my artwork.

NDEREO: There are so many Dominican experiences and I rarely get to talk about them with other people. The Dominican York experience is one, and this has many ramifications and nuances. There are the Dominicans who came in the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s… each group bringing their own stories and theirstories of the Island at different times. Then there are the intellectual, gender, economic…exiles. I sense the Dominican York identity is moving to the background. I hear younger Dominicans refer to themselves as Dominican Americans. In my opinion, Haitians and Dominicans are the first “Americans” in the hemisphere. I am saying this with the awareness that “Americanness” is still a colonial term. Would you be willing to illuminate for me the subject of Dominican identities in the diaspora? I am from an older generation and I am looking forward to continue to learn.

DO: Pues baby, we can ALWAYS talk about Dominican experiences together! Yes! The multi-generational gradation of Dominicanness can vary so much. My parents have very different migration stories and it reflects upon their experience in New York City and in the United States.

My mother’s family comes from El Rincón de Cuabanico in San José de Las Matas and they began their shift to the United States in the ‘80s using my uncle's papers. First was my uncle, then his parents. Following them were my uncle's siblings who were sent in pairs from oldest to youngest. My mother and her younger brother Jesús were the last to arrive and moved together when they were in their early 20s. They were teenagers living alone in DR and arrived in the States as independent individuals with their Dominicanness engrained. Listening to the song, Las Pequeñas Cosas by La Chicas del Can accurately describe how my mother experienced her time in the US. With a heather gray sweatshirt and blow-dried bangs, she had a hard time learning English and understanding how to integrate herself into the fast-paced capitalism of NYC. Constantly in between jobs and struggling to make full use of her associate's degree, she treated 175th Street between St. Nicholas and Audubon with the same uninhibited grace as sitting on the edge of the river eating sugar cane with friends and spitting its excess into the stream.

My father was born and raised between Bonao and the Heights. He was brought to New York City at the age of nine on his mother's papers. As a pre-teen, he was returned to the island leaving his mother and younger brother who was born in the city behind. He then returned back in his teenage years. He went to high school in Washington Heights and became fully integrated into the culture. I’ve heard stories of him dressing in grunge clothing and listening to Biggie Smalls and Maná. He encapsulated both the Dominican and US worlds with his half-baked Spanish and English, making due for himself in the city. Throughout my childhood he dreamed of returning to the island and took any opportunity he could to complain about the US while deep down understanding that he would not survive island living for long – he was too cosmopolitan for the lights to turn off randomly for hours on end and for service to be done on convenience rather than demand.

My siblings and I were all born and raised in Washington Heights. Such as most Dominicans Heights children, we were sent to DR every summer break and returned sun burnt and gloomy, dreading the exchange of palm trees for lamp posts. Fairly unrestricted time spent outdoors playing with the local kids to curfews, bundled time outside, and homework. Speaking Spanish in the home to our parents while learning to articulate, enunciate and learn how to carve ourselves into the world in English. We know the Dominican Republic because we’ve been there. We know the music, the food, and the people and yet we do not know its nuances. We do not understand what 365 days in the Caribbean is like. We have traveled more in the MTA Bus than in pasolas. In my opinion that is the Dominican diaspora. Understanding that the separation between where you were born and where the customs you were brought up with belong to gravely distant places. Both are within you, and neither negates the other. Although they may compete, they make up your DNA.

Since moving to Mexico City I’ve been thinking a lot about my “United Statesness” and how much I struggle to accept it although it’s very much present in my dress and the ways in which I speak. The tastes I’ve acquired and the judgments I make. I do believe that generationally one's sense of United Statesness consumes more of the individual the further the generational chain goes. My niece and nephew will be much more from NYC than of DR than say their father or I.

You're pointing out the multitudes of Dominicanness and your lack of speaking upon it is a topic that I’ve always fought with as a homosexual, gender non-binary, fat, first-generation Dominican American. There are not many stories spoken about individuals like us. Dominicans in media are depicted as the mythical Tiguere’s with a thousand abs and rhinestone clothing or Chapiadoras with their blown-out hair and massive ass, not much else. The fact is that those characters are just that, mythical, and don’t capture the nuances of the human experience and the richness of life. It is a shame that it’s not spoken about more and I hope that by living an expressive life I can play a part in starting new conversations of representation.

NDEREO: Where and who are you in your paintings?

DO: Aii no se jaja. In the paintings that I create, although I use my likeness I am not necessarily painting myself. In the act of processing what I look like through my cognition, and somehow capturing my ideations of who I am and how I prefer to reveal myself to the public, I’ve become a stranger that mirrors my psyche. I actually truly dislike painting my likeness because I never get it right. There is a disruption in the process that always misses and never captures me right. In paintings, I’ve used my body to symbolize ephemeral concepts such as balance/utopia or the physical manifestation of divine acts played out in Dominican culture like libations and healing through song. At times my likeness is used as a placeholder to represent individuals from Washington Heights or people from my block.

My end goal is typically to capture a rumination on topics that I don’t fully understand hoping that in the process of painting, I can arrive at a solution – such as writing in a journal in order to discern one's emotional state and how one actually feels and thinks of a situation. Through the dissection of my body, my clothing, my environments, my interactions, and my positions I hope to better understand my role within those ruminations and why I’m having them in the first place. Through the use of my likeness, in so many ways, I am attempting to have the solutions mirror back at me.

In reality, I’ve always been scared to speak for groups of people because I am not the smartest or the most articulate or even eloquent person in that group. There are others better equipped to stand in positions of speaking for others. In using my likeness I am speaking for myself about topics that can be relatable to others. That is why I create autobiographical works. I cannot speak about the lives of others because I don’t know their lives in their entirety, but I do have a better grasp of my own.

Where am I in the works? Stretched out at all of my favorite places in Washington Heights and the few areas I know in Dominican Republic. Most weekends throughout high school I would meet with one of my best friends and walk all over the Heights. We would pick each other up in either of our buildings and walk down to 158th Street and Riverside Drive and make our way to 207th Street and Sherman Avenue. Throughout those walks, we would smoke black and milds, buy nutcrackers and/or nemos, and eat tacos and pastelitos with friends in the street. We created memories within all of the hidden crevices that our neighborhood had to offer. These walks have been crucial for me because they’ve allowed me to integrate emotion and psychology into location. Creating totems and symbology of the places themselves.

NDEREO: Your paintings seem to be a document of performance, and I mean this in a laudatory way. Your paintings tell stories, they move, they are alive.

DO: I’m honored by that, thank you. I’m always afraid that my paintings might be too static due to their 2-dimensional quality. When I was a child I loved running out to play in the snow. I’ve been overweight all of my life so the lack of sweating and chaffing during the winter months of NYC was bliss for me. My favorite activity was to lay in mounds of snow. I would lay on the ground on my belly and pile snow onto the back of my head until I was fully concealed, creating a sort of snow cave or cocoon. In that mound, the world would become quiet leaving me in isolation. I would shut my eyes and lay in this mound for much longer than I should, frequently returning home frost nipped. Similar to the stillness within those mounds, I think of my work as the images that rest behind my eyelids which can only be seen when I’m concentrating hard on a subject. I imagine myself with my eyelids shut tight, holding my breath, and turning myself into a fist, finding the answers within that crevice – that isolation. I am at times scared that the works can be too static because what I am aiming for is stillness and quiet.

Although the concepts I am explaining can be loud for their emotional weight, I tend to view them as whispers that are just audible and spoken under the breath or as mental dialogue. As someone that is told that I mumble quite often, my work doesn’t aim to be flashy or groundbreaking but is meant to function as a tender one-on-one conversation with someone you trust. There may be tears, volumes may rise from anger or laughter, and even awkward eye contact at times, but the moment you walk away from the conversation I hope that the most important aspects will be communicated.

NDEREO: What does it entail for you to return to the Island?

DO: Returning to the island is a moment of reconnection and most importantly reclamation. Allowing myself to sit in spaces of discomfort openly, as my whole self, and force others to acknowledge and get to know me.

I am currently in the process of organizing a move to Santo Domingo, an action that I never thought I would ever want to make. When I was a child, I disliked my trips to DR because my parents filled me with so much fear for the island. There were countless stories of someone being robbed of their jewelry, being taken by kidnappers, or being shot in the street for being at the wrong place at the wrong time. During my visits as a child, my grandparents would keep my siblings and me locked in the apartment building, only allowed to play in the street while surveilled. Only an aunt who we stayed with seldomly allowed my siblings and me to roam the streets openly and make friends with the neighborhood children. The months spent with my grandparents were filled with ice cream and boredom. Yet, the moment I moved to Mexico City, I knew that my time here would be limited and that whatever I thought I needed was actually in DR. I instantly knew that my time in Mexico was meant for building up the constitution to then go to the island and heal any open wounds I carry. Being on the island as an adult will allow me to chip away at my concealment and grant my family access to experience me so that we can finally connect in ways that we both deserve, force me to reconstruct my views of masculinity, and fortify my trust towards men, establish a new view towards DR that is not centered in fear and exoticism and instead based in reality and my own personal experiences. Moving to Dominican Republic means removing the fog that is standing in the way between my and myself, me and the island, me and others.

NDEREO: I thank you for conversing with me and I am looking forward to continuing to seeing you paint and be.

DO: Thank you!! This was such a pleasure. It was refreshing to reflect upon my work and myself in ways that I haven’t forced myself to do as of yet. It’s such an honor to have you, such an inspiring and wise individual, in my life! I look forward to continuing to see all that you do and all the ways you welcome us to hyperfocus and reflect upon all aspects of existence.

Besotes!

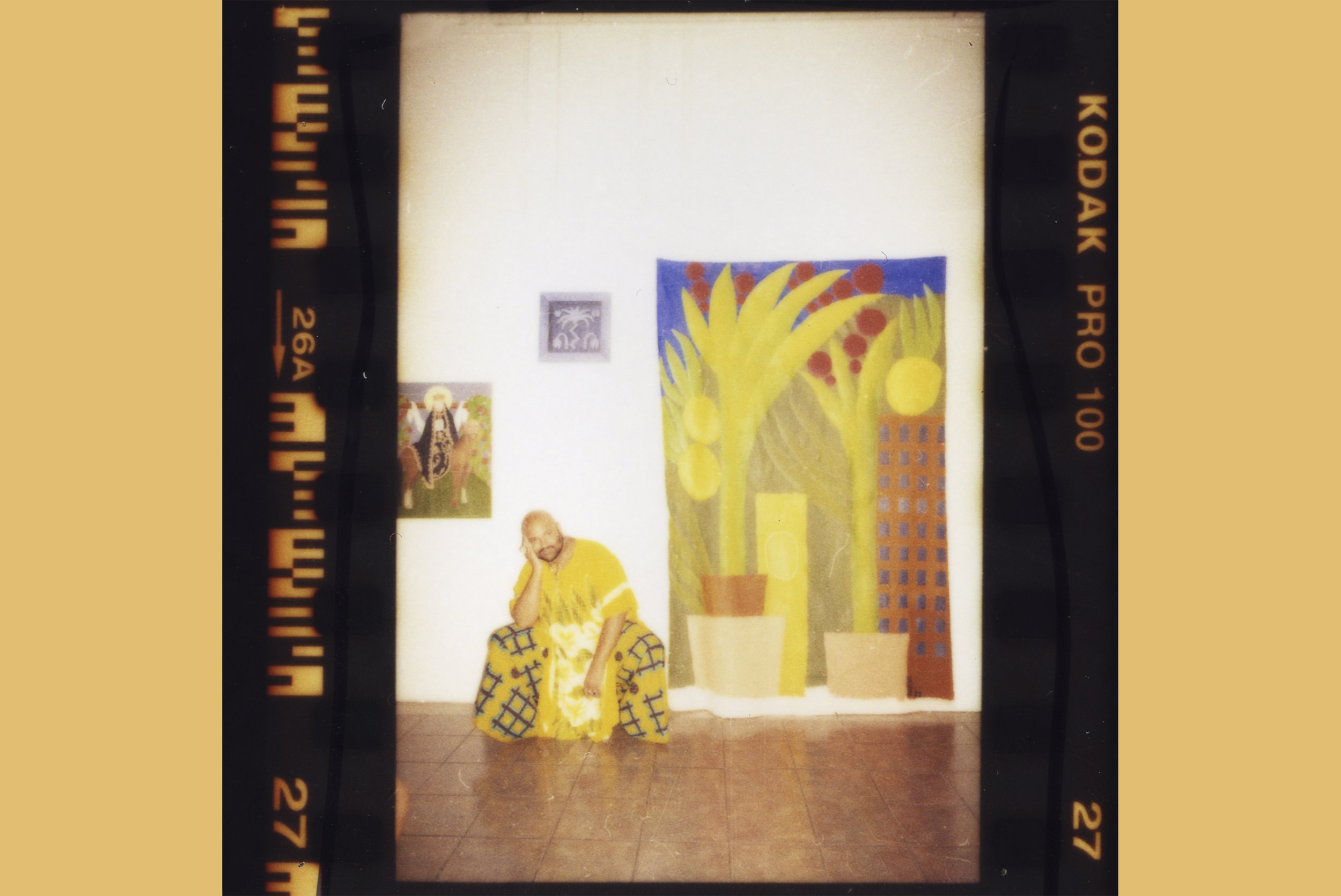

All images courtesy of Devin Osorio

Davin Osorio / links to work and publications: Website / Instagram

Devin Osorio (b. 1993, New York) grew up as a first-generation Dominican American in the northern Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights. Osorio takes inspiration from Dominican culture and folkloric traditions, including a strong emphasis on textile patterns. These cultural influences merge with biographical details from Osorio’s lived experience, yielding paintings that function as secular reliquaries, commemorating a life lived between cultures.

Devin is a multi-disciplinary artist based in Mexico City, Mexico. Using shared and self-reflective symbolism, Osorio honors Dominican culture through shrine-like paintings that incorporate plants, animals, and glyphs to create a visual vernacular of and for the Dominican American community. Osorio’s work has been exhibited in New York, Atlanta, Georgia, Los Angeles, London, Mexico City, and Madrid, at galleries including Calderon Gallery, Wave Hill, The AHL Foundation, REGULARNORMAL, and Charlie James Gallery. Alongside gallery Adhesivo Contemporary, Osoro exhibited a solo showcase in NADA Miami 2022. Osorio was the 2022 Spring Artist in Residence at New Wave in West Palm Beach, FL. Osorio earned a BFA from Savannah College of Art and Design.