Ernesto Rivera

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles Morel: Ernesto, we met through Scherezade García. I think that the three of us attended Altos de Chavón in the Dominican Republic. We do represent different generations of students at this school. Scherezade and I were there in the 1980s and you were there at least two decades after. What year were you in?

Ernesto Rivera: I attended Chavón, The School of Design, for only a year—actually, just a few months between 2016 and 2017. Before that, I was living in Mexico City, pursuing a master's degree in design theory and history at UNAM, which lasted three years. Immediately before enrolling at Chavón, I worked for a year in my previous profession as an interior designer for a firm in Santo Domingo. Interior design was my first university degree and the work I did for a long time. I met Sherezade later, in 2017, when I arrived in New York for the two years of Fine Arts at Parsons.

My friendship with Sherezade is interesting, and whenever we talk, I feel very energized to do creative things. Sherezade is like my bridge to other generations of artists from the Dominican Republic and to San Cristobal, the town where I grew up and where the Renville family, the maternal side of Sherezade and her sister iliana Emilia García's family, is from. And I think that's beautiful because I don’t know if you know that their father, Luis Reginald García Muñoz, is a prominent bridge engineer in our country. Through the social bridges Sherezade builds, I was able to connect with you. In 2018, I attended a talk you gave with artists Pablo Helguera, Chloe Bass, and Martha Wilson at The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, but I didn’t dare to approach you. Perhaps it wasn’t the right time. I still remember your reflection about the keys. I truly believe that what really connects us all is poetry.

NDEREOM: I did not know that you were in the audience! Regarding Chavón, I vowed never to return there which, when I attended this school, was in the city of La Romana. I felt that I did not need to go back to a place where I co-created so many memories and where I lived one of the freest times in my life. We could talk volumes about this mythical place perched on top of the Chavón River in the Dominican Republic. I was a student at this place before art became thoroughly engulfed by the market, networking, branding and all of that stuff. How was your experience there?

ER: "No one can cross the same river twice," says an ancient saying. And that is true. Neither the place of origin is the same nor am I the same. Frankly, I have never been able to see Chavón as a mythical place. Demystifying Chavón has always been my relationship with the school. I arrived there when I was thirty-three years old, with two university experiences, after living abroad for three years, with ten years of work experience, having left a religious community, and fully assuming my own personal identity. That is to say, before being a student, I was a heretic. So, I always found the idea of a magical or dreamlike place very suspicious. For me, arriving at Chavón was like entering a small theater, not as a spectator, nor as an actor, but as someone observing from behind the scenes the performance of an act at play: the affected behaviors, the dramatic effects of emotions, the performativity of authority figures, and the voluntary collective acceptance of a script imposed by others were always visible to me.

Don’t get me wrong. It was a place of much personal learning because I could test my own motivations and the daring decision to be an artist in the Dominican Republic. But the collective emotional devotion to Chavón sometimes seems like excessive enthusiasm. Now I believe I understand it in its proper dimension. I also recognize that the school is a historical and political project that emerged under very particular national circumstances that are not always transparent. What does it mean to place an art school in the midst of a tourist paradise accessible only to 1% of the inhabitants of a relatively poor country? The invisibility of the social injustices behind that scene of privilege and glamour is, in my opinion, the tragedy of our national art. Entering Casa de Campo is at the same time leaving the national reality. For those who are not part of the alumni collective, Chavón appears as an image upon which many social prejudices are projected, which are also the common prejudices of a small colonial island with a very authoritarian, conservative, and prudish culture. An essentialist view of the school's identity has been tied to its location. But the true identity of the school lies in the people who work there and have passed through it. This is something the school's owners do not fully understand, and it's a shame because many stories are being lost. Chavón, which is in reality a private foundation, has survived thanks to the dual public efforts of a State that operates with much opacity and a large group of alumni who maintain an emotional bond with the school because of the shared memories they don't want to see lost. It's a fascinating story, and I hope that someday someone takes on the task of writing it... even if it’s in the form of a novel.

In the Dominican Republic, there is a lot of fear of freedom, particularly of freedom of thinking, and that has hindered the development of the arts in a broad sense. The main responsibility for any Dominican artist is to find their personal voice and create art from that place of emotional maturity. Everyone who self proclaimed a black sheep of Chavón becomes a mirror for the school, and that social service is necessary to train artists who can navigate the tentacles of dehumanizing financial capitalism out of a bubble.

NDEREOM: I was only 19 years old when I entered Chavón. I had come out of three years of medical school and I was shifting paths. I had never studied visual arts before and I had put all of my efforts into studying theater, where I studied with the luminaries of our country like Rafael Villalona, José Núñez and Elvira Taveras, among many others. I started theater when I was 8, and at that early age I was able to socialize with intellectuals of the magnitude of Delta Soto and Augusto Féria. I acted in a play where Augusto Féria played the main character. I was at a loss at Chavón. I wanted to break into performance art and the school was centered on design, so professors did not think much of me. And, while I agree about the huge mirage that Chavón represents, I feel great that I was actually able to navigate this institution at a young age and leave somewhat intact. It was not easy for my mother financially. While I come from a family of prosperous Lebanese immigrants, my own immediate family did not have the means to send me to Chavón. There were times when I went hungry in school or stole groceries at the fancy supermarket in the village in order to feed myself, or dressed as a tourist and attended the fashion shows at Casa de Campo so I could eat their hors d'oeuvres. The fact that I could pass for a European tourist of some kind, helped, and I understand that this privilege was not available to my Black and Brown classmates who could not take on the disguise of a white looking traveler.

You followed the path that many of us at Chavón did. You moved to New York City. In retrospect now I think how, at least my generation, was not prepared by this school to share our talents with our own country and people, but to leave the island as soon as we could. However, it could be said that New York City is an extension of the Dominican Republic; a satellite city outside our country. Tell me about your transition to New York City in any way that you may wish to do so.

ER: In this past year, I have come to the conclusion that the Dominican Republic shares with New York an artificial acceleration of time. This can be perceived in our music (note that Haitian music seems to be more slow paced)... in the frenetic use and consumption of social media, or in the speed with which we speak our rough and violent Spanish. I never understood why my Dominican friends always had such a packed social agenda, jumping between birthdays, weddings, and baby showers. The rest of the Caribbean seems to live in more episodic time spans, but in the Dominican Republic, time is continuous, without any interruption. The Dominican Republic is a 24/7 live performance. If there is a culture prepared to survive the neurotic New York atmosphere, it is the Dominican, because I feel our neurosis is more clinical. It was not difficult for me to integrate because, in my case, returning was never an option.

I have to be honest about my privileges. I cannot compare my experience with the multiple sufferings and collective traumas of a broad community of Dominican immigrants who were deprived of their country and loving ones by government inefficiencies and the insensitivity of the wealthiest. One of my blessings was arriving when I already had some of my family here, studying for two years on a scholarship, finding a very stable job as an archivist, and having a network of friends who have also been a great support. I am aware that I am part of a larger Dominican diasporic community and that what I build here rests on the foundations of that ancestral legacy.

Like everyone who arrives in a new territory, in the first years I was constantly comparing my new reality with my previous experiences, but I can tell you that since 2020, New York is my home and the place where I began to put down roots. I love the energy of NY; this infinite mix of cross-references stimulates me. It is a fertile place to think and create things.

NDEREOM: To some extent, I was always an immigrant in the Dominican Republic, and I was raised to think like a Lebanese immigrant and to save resources. This would clash with the impetus in Dominicans for celebrations. I have come to value and embrace Dominicanness more and more in my role as an exiled in the USA. This, in fact, is where I learned to be Dominican, whatever that means, which I know is highly subjective. I therefore consider myself Dominicanyork.

Going back to your work, you serve as an archivist/registrar for another artist. You also continue to develop your creative praxis; and you write, discuss art in ways that I find quite inspiring. How is to balance all of this?

ER: The activity I enjoy the most is learning and feeling challenged by the vastness of the world. The scale of work in the artist's studio where I work is extremely different from the scale of my personal practice in my small studio in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. But the contact between these two worlds, I believe, is reflected in the materiality of my art or the ideas in my texts. A shared sensitivity among all these spheres is that of essay writing, which in Spanish can also be translated as ‘rehearsal’. Essay writing is working with remnants and starting a conversation with the fragments at hand. That's why I am enjoying this conversation with you so much, because it is so instinctive. See, the two rooms in my apartment overlook a magnolia tree in the backyard, and sometimes I watch the house sparrows that arrive flying without warning and hop from one branch to another, happy in their improvisation that seems purposeless but is part of the tree's architecture and the sounds of my thoughts. No day of my work is the same as the previous one, and my personal studio is like my own magnolia tree, where I can come at any time and jump from one creative gesture to another. What people see as results are the remnants of these continuous improvisations, which are only connected by their being traces, the signs of a human presence.

NDEREOM: I am very enjoying our conversation and I am aware that this diálogo can go in so many directions and extend itself considerably. A week or so ago we joined a Zoom conversation with some Dominican colleagues on the island and in New York City. The subject of the discussion was the generation of the ’80s in the Dominican Republic. I learned so much from this program and I was able to translate some of the information shared, however specific to the Dominican Republic, to the arts as practiced more broadly and through our current times. Some of the points that came up were those of curators, institutions, and the government in regard to the arts. I come from the generation of the ’90s when Art was not the colossal capitalist business that it is now. At least not to that extent. How are you, and perhaps some in your generation of creatives, including curators, working to undo the structures that, on the surface, seek to dismatle the outdated systems that Art continues to perpetuate?

ER: That online talk was very enlightening for me, not only because of the archival material they showed us but also due to the reflections that emerged during the open mic session. These types of meetings always provoke a lot of thought in me because they help me understand other perspectives and piece together a possible history of Dominican art, which still appears very fragmented and dispersed among artists. In a sense, I think that this feeling of impossibility in completing these individual histories is what keeps me attentive. And I think about how inadequate the current methodologies are for documenting these experiences, because given the importance of oral tradition in Dominican culture, one would think that these kinds of meetings to share lived experiences would be more common, but they actually are not.

Perhaps the methodology of microhistory would have more to contribute to this project of historical documentation, but the use of chronologies and very conservative ways of narrating things, with no complexity or nuances, still carries a lot of weight among Dominican institutions. It seems that highlighting individual achievements is more important than understanding ourselves as a collective. To be honest, I think gossip among artists has more relevant things to say than any book on Dominican art history. It seems like everything is yet to be written, and even when it is written, something is always left out. I find what is left out to be fascinating.

Now, regarding capitalism, I honestly believe that the current state of financial and platform capitalism is a rather bizarre monster with a surprising capacity for reinvention. Think about it: capitalism emerged from that first great accumulation through the violent conquest of our lands, and since then, it has reinvented itself with surprising agility. Capitalism is like those AI images that keep regenerating with each new input. But art has always been linked to power and those efforts of capital accumulation. I think what’s needed is to humanize and diversify the ways we attribute value to artistic experiences—in other words, not letting money be the sole determinant of what has or doesn't have artistic value. In the Dominican local context, that seems very difficult to achieve because the ways of conceiving art or what has cultural value are still very rudimentary. The first art fairs in our country emerged as extensions of agricultural fairs, and in that sense, I believe that vision of art as an appendage of something else that determines it still survives.

We haven’t managed to emancipate art from the excessive control that wealthy families exert over the content that needs to be created and shared. And precisely because of this, little effort has been made to deepen conversations and to develop professional profiles that think with true scientific criteria about the dynamics of the social order, which is where any creative production fits in for me. This happens with all forms of artistic expression. If you talk to people in theater, dance, or writing, you realize that this sense of orphanhood prevails, which has always been a hegemonic political project to stifle any possibility of feeling and imagining other ways of living together. That’s why I say that for artists of my generation, but even more so for younger artists, the main challenge is to maintain optimism. Dominican cultural institutions, still represented by few individuals, have failed younger generations because they have preferred to appease money rather than create deep emotional connections among people. I belong to a pre-internet generation and have witnessed this progressive deterioration of the achievements that could have been made with the return to democracy in the 1980s and the idea that popular culture also had value.

But despite all this, I can tell you that there is a group of few creatives that resists all these dynamics by working from the margins. That’s why I believe our strongest art has always been marginal. It's something that those looking at us from the outside still fail to grasp because there are two or three people who are like official charming sirens controlling the official narratives. For me, the best form of resistance against the progressive financialization of everything is to cultivate strong bonds of friendship between people and to reclaim the value of two seemingly useless disciplines: poetry and philosophy. The real tragedy of Dominican art is art without poetic content.

NDEREOM: This makes so much sense to me, personally. I can see more clearly why I have been moving into writing and now into dance and movement. I find that most of the visual arts have succumbed to advertisement and to what I call Instagram art and selfie art. Curators know who the good artists are, and yet many of them have to play the game in order to secure their jobs and put food on their tables and have a roof.

There is not a deep questioning within Art about consumption, the use of materials that continue to destroy our planet, as well as roles and gatekeeping. Interestingly, Art has been so critical of institutionalized religion and its hierarchies and, in my opinion, the hierarchy in the art industry (as I call the art world) resembles that of the church, with its popes, bishops, and beatified saints. I am curious as to new fields where creativity can thrive unencumbered by all of the BS I try not to give my attention to.

ER: LOL, all that BS. I totally get you. But I wish it were something fascinating to witness. When you watch religious rituals, at least you can enjoy the theatricality of the liturgy, the coordinated movement of the bodies, the detail of the vestments, the scents of the offerings—you know, all those things designed to excite the senses. But the things you're referring to have lost all magic, any power of evocation. I'm not talking about sacralizing art; in fact, I believe there's more power in profanation, in the intentional return of art to the realm of the earthly and communal.

But what I perceive now are these very sectarian behaviors, people like automatons who do the same things, make the same art, say the same things, operate under the same codes, and exist within these pyramidal relationships where they have to constantly flatter to climb the ladder. It's a performance so predictable it's become boring. It has lost the aura of novelty it had between 2000-2015. You’d think that after the traumatic experience of a global pandemic, there would be a slowing down of processes and a desire for reconnection. But "returning to normal" has actually meant ignoring the opportunity for certain lessons, and now we're very divided—between those of us who want to see real social changes -perhaps more than ever– and those who want to keep living as if nothing is happening. It's truly unsustainable. It's an extension of our planet's economic unsustainability. I mean the responsible use of resources, including the personal resources that any artist has in order to create and say things.

I'd like to see more people working in culture with greater social and ecological conviction. But it's difficult to break through the echo chamber of discourses that are disconnected from life. I always say that the Dominican Republic is the country with the most wannabe celebrities per square kilometer, and social media has only exacerbated this collective pathology. Sometimes I wish I could be completely invisible, you know, make a kind of secret art that people discover by accident, through clues or vestigial remnants. But I'm always betrayed by the urge to speak out. There's no force that drives my art more than being a heretic of everything. But many artists, out of the need to belong, have forgotten the necessary art of knowing how to renounce.

The farce in the art world is directly linked to the farce in the political world. We are facing a crisis of trust because our leaders are not honest voices. The ongoing genocide in Gaza, perpetrated by Western Zionist lobbies, has, for over a year now, exposed the emptiness behind many cultural discourses that, before fall 2023, were considered paradigms of social engagement. In the face of this relentless bloodshed and the depravity of humanity, it has become nearly impossible to sustain any pretense of such discourse. What does it mean to be an artist amid all this? Amid a genocide in Palestine, funded by our taxes, amid the sadism of western democracies… and amid racist state policies in the Dominican Republic targeting poor Black individuals. These realities are truly sickening, and we must resist these structural violences, but equally important, we must empower people to imagine a better future. Both resistance and imagination are deeply connected to feeling—feeling the struggle now and feeling the future possibilities. The essence of art is to reclaim those feelings for the sake of life, any life.

NDEREOM: There is a tremendous amount of tearing apart, knocking down and demolishing going on. Most of it is long needed. However, I ask myself as to what is being built. Sometimes, my response is that Art is so bankrupted that perhaps my call is to envision new fields where creativity can flow again away from the devastation of professional development workshops and tips for how to get a commercial gallery. Please chime in.

ER: I believe it's important to maintain a balance between building and demolishing. Sometimes, the best way to repair a house is to tear it down and rebuild it. This is, for example, my view on many cultural institutions in the Dominican Republic that have perpetuated numerous "structural flaws," and at any moment, everything might come crashing down. Well, I say, "Let's leave this building that's about to collapse together, tear it down, and create something new from scratch." But it's like the parable of Simonides of Ceos, where it's hard to convince people that are having the most fun to leave the banquet and survive.

However, the most dangerous aspect of that compulsion to destroy, which you point out, is when it's done out of anger or impulsiveness. Even to tear down a building, you have to calculate the costs, and much more so to create something new. It's what engineers call "cubicar" (calculate costs per volume) which is basically a lot of strategy and planning. When I write very critical articles, I've sometimes received responses labeling me as a destructive person, but I believe what underlies that perception is a reluctance to engage in honest conversations. It's impossible to think that we will all agree on everything, and that is why politics is relevant, but when it comes to things that are truly rotten, there shouldn't be such a diversity of opinions or this extraordinary ability as we commonly say in our country: ‘to justify the unjustifiable’.

American culture has a lot of that. You watch the news, and it's pure ethical juggling from the most powerful USA institutions. That lack of honesty has been normalized and spread at all levels. We saw it with Trump, we saw it with Biden, and it seems we'll keep seeing it regardless of who the next president is. While it's true that truth is always an interpretation, there are still rules and principles for interpreting. When there's so much lack of transparency, what is presented to us as the most plausible becomes the substantive truth of things.

The true role of art is to enrich interpretations and open up possibilities, sometimes to demolish and other times to build. Both are necessary. Over the last two years, I've been involved in political work in the Dominican Republic through a minority political party, and I initially thought that, as a simple artist, I had little to contribute to them. But it's been fascinating to realize how small gestures that open up new interpretive possibilities can challenge established power structures. And that can be seen as either wanting to destroy or wanting to build, depending on whether you're inside or outside the building.

NDEREOM: Creatives have given too much power to a structure that cannot function without us. No artists or creatives = no museums, no curators, no biennials, no galleries. Power is usually misinterpreted and seen in connection to a few, to scarcity, and to dominance. The power I am working to reclaim as a creative is one that allows me to share this divine force with others and let it travel through me rather than grant me a place at the top of a social pyramid of any kind. What spaces might come to mind for you to set creativity free?

ER: I wish artists were more aware of how they are being instrumentalized by power structures and how their creative work is used to generate money for banks. Not because it's the only solution to the problems artists face, but because it would give them greater agency in deciding when they want to participate in these social dynamics and when they don't. Personally, I'm not against the art business; I find it a fascinating world where there's much to learn to break out of the bubble in which artists have voluntarily enclosed themselves. However, there is a need to diversify both the ways of doing business and the ways of creating art. The new ways of doing business should be the responsibility of people in the business world—a talent I fortunately don't have, but I value when I see it working for the common good.

To answer your question more directly about how to emancipate oneself from the control exerted by those in power, I'll share my personal strategy. My strategy is to have a 9-to-6 job, which fortunately is related to the art world. But if that weren't the case, I wouldn't have any problem working in another field as long as it covers my material needs and, above all, allows me to maintain the freedom to speak my mind. It's the strategy of the Apostle Paul, who made tents so as not to corrupt his preaching by accepting money that came with strings attached. Well, it's not that being an artist means being specially chosen, but sometimes I feel that what’s needed is more commitment and seriousness about the craft itself.

I know it's not a popular strategy because some people aim to live exclusively off their art, and that's also fine. It's a life choice that I find very brave. But my approach to being an artist is more aligned with the mystique of certain cultures where being an artist doesn't mean being an enlightened individual who belongs to a separate class, but rather it's a way of living in the world, integrated with all forms of inhabiting it. In this sense, being an artist would be like being a mail carrier, a gardener, a supermarket shelf packer, or a nurse—essential professions with little monetary appeal. Protecting the freedom to speak is the only true responsibility of any artist, and once you have that freedom, it's about saying something meaningful. Sometimes the most meaningful thing is to say nothing and continue working in silence. Obviously, business people don't like that because "what isn't exhibited doesn't sell," hence all the showcasing.

NDEREOM: Like you, I have refused to sell my soul to the D… The perks are enticing, but I value my freedom more than the goodies. As an independent creative I do not have anyone telling me what I do, so that my work can be traded for dollars. I am happy with being a passerby rather than to try to get a ride on the curated guaguita of success.

Is there anything that you would like to say, to ask, to complain about, or to celebrate as we conclude?

ER: Nicolás, I think if we sat down to talk, we would never finish. That’s beautiful because, in a few words, it’s how I imagine true friendship.

NDEREOM: Thank you so much for the voice that you bring forward. It is needed. Let’s talk again.

ER: Thank you for creating the conditions for this gathering. I hope it happens again soon.

All images and videos courtesy of Ernesto Rivera

Ernesto Rivera’’s links: Website / Instagram

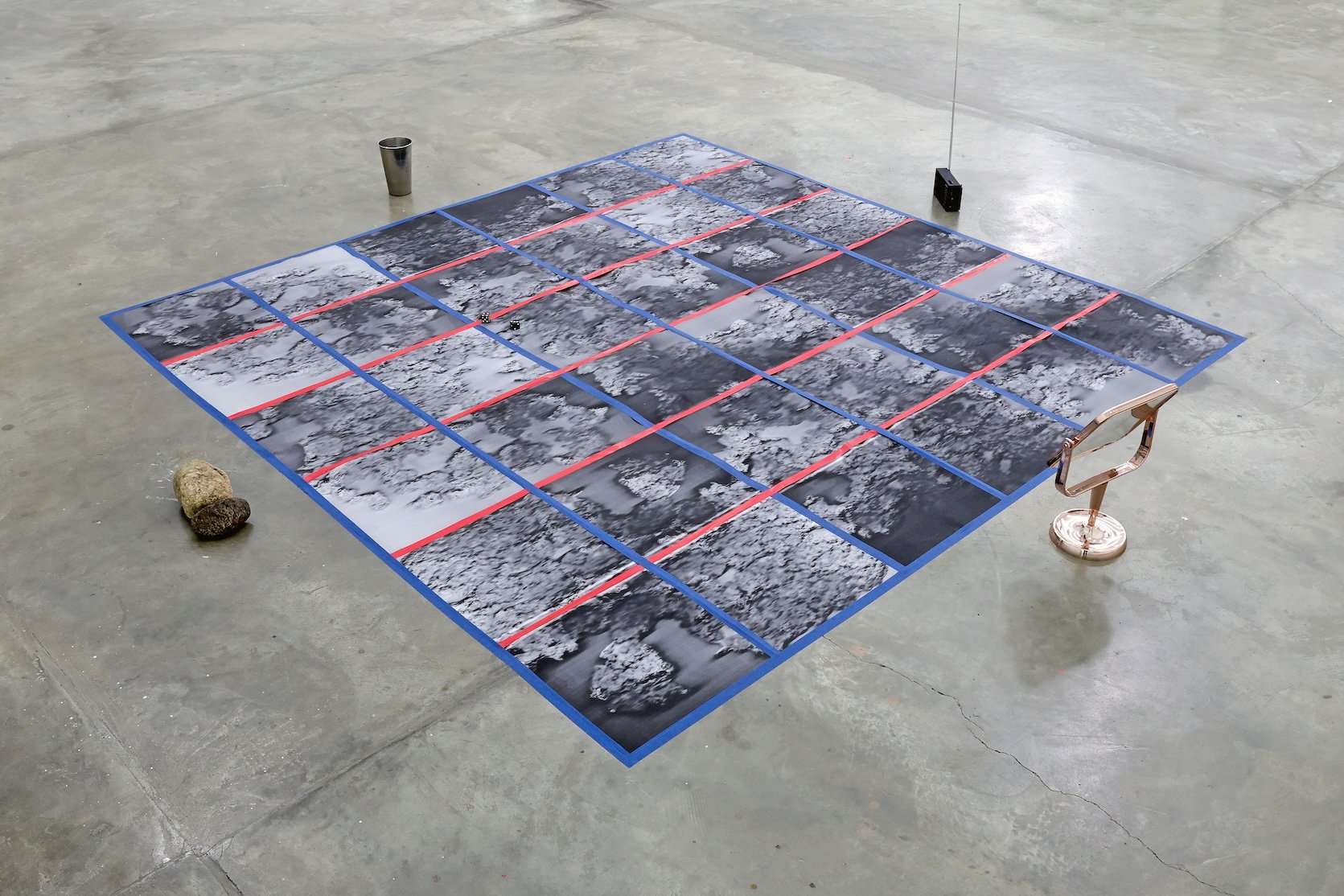

Ernesto Rivera (b. 1983, Santo Domingo) is a Dominican artist based in Brooklyn, New York, since 2017. His practice primarily focuses on drawing and installation. Ernesto completed coursework for a Master’s in History and Theory of Design at UNAM, Mexico City, and earned a Fine Arts degree from Parsons School of Design at The New School in 2019. In addition to his artistic work, he serves as an archivist and registrar for a private collection. He also contributes cultural criticism articles that are widely read and recognized among younger generations of thinkers in the Dominican Republic.