Ivan Monforte and Nicolás

Office Hours (OH) and the Museum as a Testing Ground

Nicolás Dumit Estevez: Office Hours (OH) was born in 2013, as a result of an invitation by Chus Martínez for me to work in conjunction with her on an exhibition that she was curating at El Museo del Barrio, New York. The initial idea was to engage the permanent collection; a plan that eventually changed into a project that would take place at El Café, outside of the galleries, and which proposed to approach El Museo as a holistic work of art. Soon after Chus left El Museo, I was faced with the challenging but rewarding opportunity of giving shape to Office Hours (OH) throughout the entire hosting organization as opposed to the permanent location that was originally meant to serve as the project’s physical base, El Café. I found myself responsible for activating an ephemeral and diffused artwork that entailed exchanges, discussions, partnerships and collaborations with all of the different departments at El Museo. These exchanges also involved audiences, guests and artists who were in turn asked to generate their own events. Office Hours (OH) has therefore been responsible for hosting workshops, celebrations, interviews, and a residency with seven artists. Yet, while committed to embracing art as part of a larger experience called life, Office Hours (OH) did not host a health-related action, and so by way of this interview I would like you, Ivan, to bring this important element to the project. I am doing this under the premise that your piece There But For The Grace Of God Go I, presented at Longwood Art Gallery in the Bronx in 2006, proposed new paradigms for one to relate to the art gallery space. It also questioned the role that galleries and museums are meant to play in the twenty first century. Can you please describe the specifics of your piece?

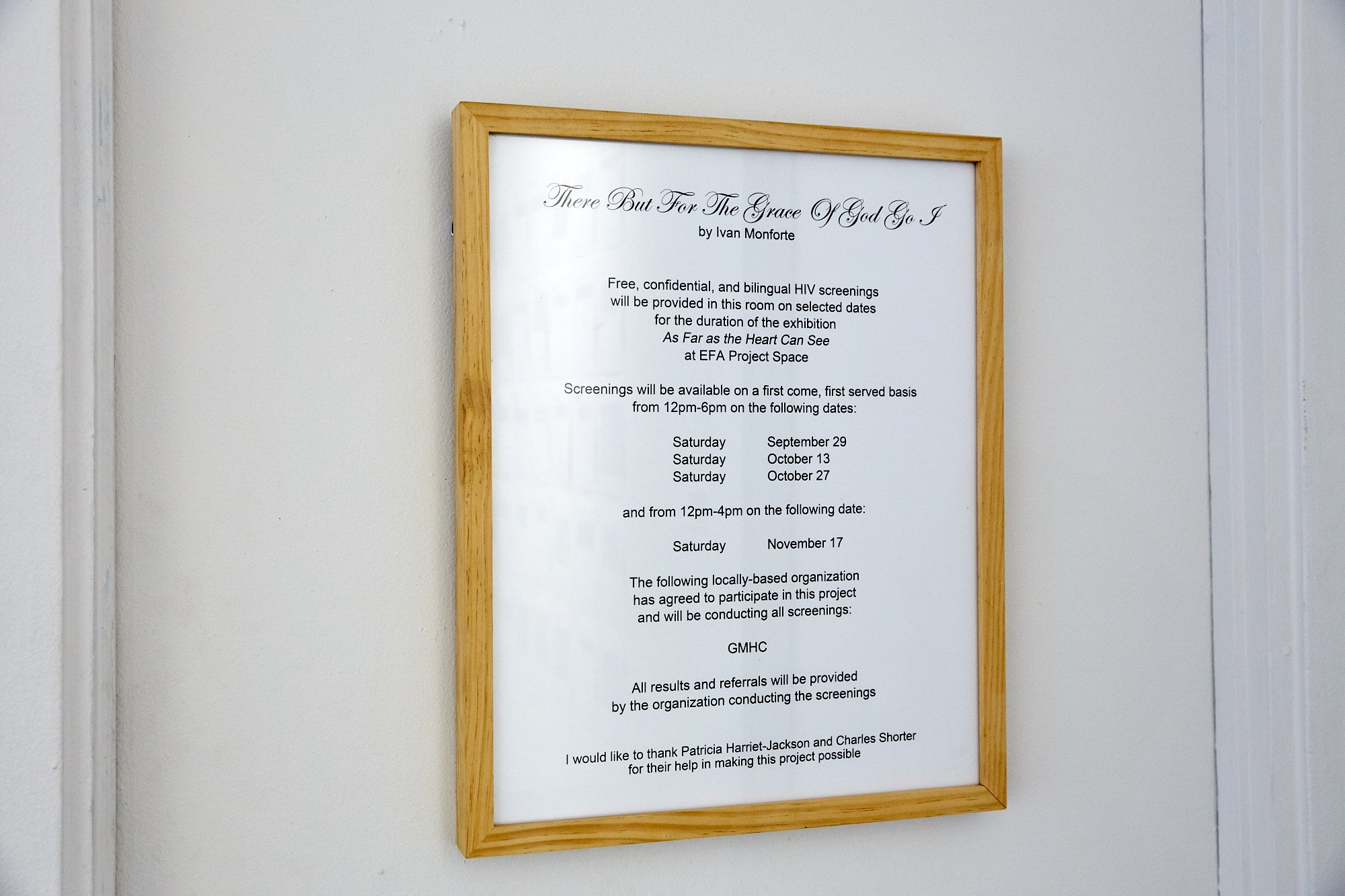

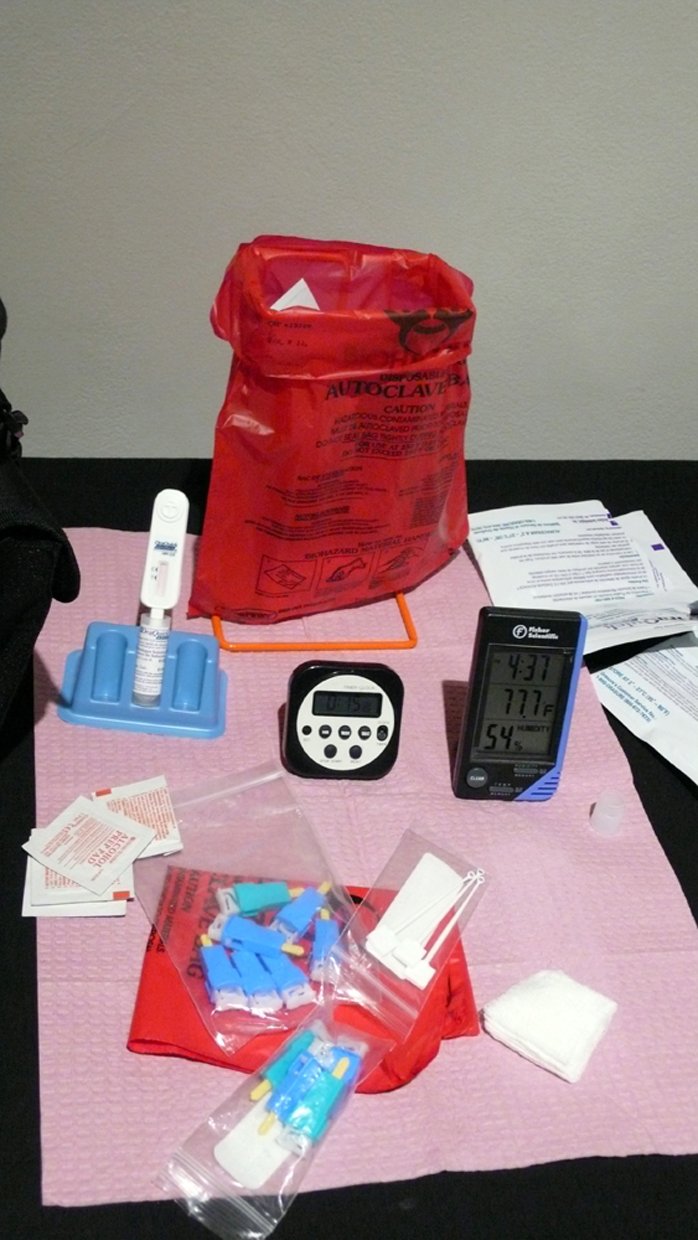

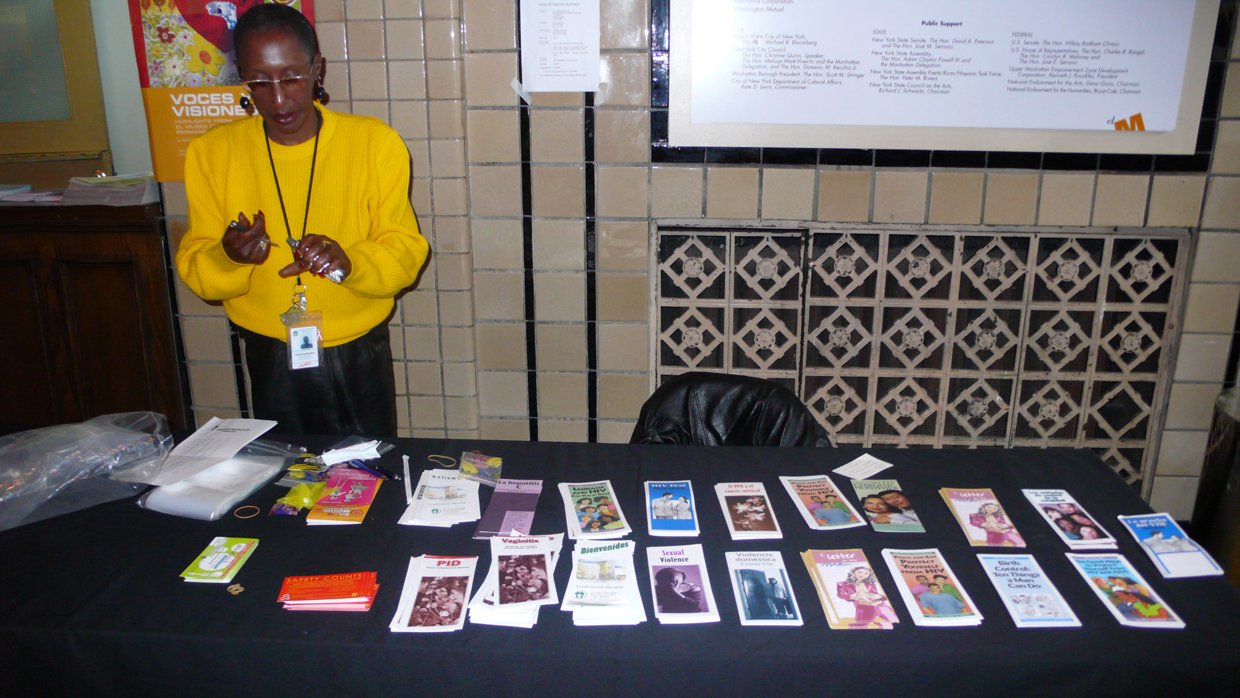

Ivan Monforte: There But For The Grace Of God Go I consists of creating a space in a gallery or a museum to provide free and confidential rapid HIV screenings and referrals to visitors and the general public during scheduled dates and hours. All tests and referrals are provided by a local community-based organization whose mission is to provide this testing to the local area. Results are available within 20 minutes. Whenever possible, testing is made available in both English and Spanish. Generally, an empty room is used to conduct the HIV screenings, and a table is set up in another area where a worker from the local organization providing the screenings can give information to the public about HIV/AIDS, refer them to an alternative site for testing outside the gallery/museum and, when allowed, provide safer sex supplies. The project takes its title from the disco-era song of the same name by the group Machine. A sign is placed outside the door where the testing will take place, listing dates and hours that testing is available. One tester and one outreach worker from the agency testing would arrive about 30 minutes before the beginning of each performance to set up. I would meet with each worker and have a conversation about expectations or regulations we needed to follow—for example at some institutions, we were not allowed to provide people with safer sex materials out in the open, but we were allowed to store them discreetly and provide them if the person requested them. During the performance I walk around with a clipboard and introduce myself and the project and sign people up for tests and escort them to the room where the testing is taking place at their appointed time. Once we arrive at the room, I introduce them to the tester and then leave the room. HIV testing is confidential, so I do not have access to any information about the individual, except their initials, which I use to track them on the sign up sheet. Sometimes I would run into someone after they got tested and we would have a brief conversation about their experience. These moments were almost always positive. However, the introduction of myself and the project sometimes led to intense and emotional conversations. Talking about HIV and AIDS is still difficult for some people. For some, talking about the medical system triggered tears. For me it often became an opportunity to talk about art, public health, activism, and AIDS, and their relationship to each other, as well as educate people about HIV prevention, testing, and treatment. I was a sort of HIV Dr. Ruth.

NDE: What were the reactions that your presence at Longwood Art Gallery generated at an institutional level? For those not familiar with this space, the gallery is hosted by Hostos Community College, a two-year program mostly attended by new immigrants to New York City.

IM: On an institutional level, I received full support from Longwood’s director, Edwin Ramoran. Edwin allowed me to conduct the testing in the gallery’s kitchen, since it had a door and could provide the most privacy. The first time the work was performed everything went smoothly. We posted a sign outside the gallery by the front desk at the main entrance of the college, and encouraged students and workers to participate in the project. However, it didn’t take very long before we ran into problems. During the second iteration of the project in the space, a security guard from the college came into the gallery as we were setting up for the day’s performance and informed Edwin and myself that she was shutting the performance down for the day. She apparently read the sign by the front desk and felt compelled to stop the project. After it got shut down I was asked to provide a very detailed explanation of how the tests were being conducted to Edwin, who then forwarded the information to the head of Public Safety at the college. An anonymous committee was then formed to evaluate the “appropriateness” of the performance in the space and their findings were that HIV tests could not be conducted in the gallery space because it was taking place in a kitchen where food was prepared and could potentially pose a health hazard, and that I would be offered an empty classroom to use on the third floor of the college. When this happened I did some research and ended up having a conversation with the person in charge of HIV testing for the entire state of New York at that time. She informed me that there was actually nothing inappropriate with my project and that there was no potential contamination to any food that would be prepared in the space since the organization was using oral swab tests, and not blood tests (HIV is not transmitted through saliva). One interesting clarification she also made regarding privacy and confidentiality around HIV testing is that a private room was not even necessary to conduct a test. She said that I could literally test a person on the street in broad daylight - as long as the person getting tested was willing to sign a written consent form. It was interesting to argue science and law, while being met with anxiety and willful ignorance. But at least they didn’t shut the performance down altogether, so I can’t exactly say the school was not accommodating and willing to work with me and Longwood. The students, for the most part, reacted very positively to the performance, and a few signed up to be tested.

NDE: I am fully aware of the anxiety that waiting for the results of an HIV test can impose on one. Did you offered any post-intervention support or counseling to those who participated in your action? Were people who participated in your intervention entitled to a follow up?

IM: As a certified HIV tester, and a participant in HIV testing, one of the things I wanted to be sure of was that everyone who participated would receive non-judgmental and harm reduction-based pre- and post- test counseling. All participants were given referrals after their tests if they needed any kind of follow up testing or counseling. HIV testing can be incredibly traumatizing when the tester is inexperienced or judgmental. I personally have had horrifying experiences getting tested—particularly when accessing services from the New York City’s Department of Health. In 2004, I tested at a DOH center in upper Manhattan and was told by the doctor examining me that I probably should’ve gone to the center in Chelsea because they were “better equipped to deal with gay men,” and was also forced to sit and watch Tom Hanks die of AIDS-related complications in the waiting room as they played the film Philadelphia on the television for everyone who was anxiously waiting for their results. Needless to say, I was personally invested and determined to create an environment that was friendly, welcoming, and private.

NDE: Our common friend and brother in art Edwin Ramoran was a driving force in the presentation of There But For The Grace Of God Go I. Edwin has been a catalyst for LGTBQI related initiatives in the arts and beyond, and one of the most forward thinking and radical curators in New York City. What was his involvement in your piece?

IM: As I stated earlier, Edwin was very supportive of the project. He was receptive to it from its planning stages and helped navigate the conversation with Hostos after Public Safety shut down the project and relocated it to a classroom. In many ways, Edwin is an amazing curator—reckless and brave, he has always been an important and incredibly underrated voice in the New York art scene.

NDE: In what way would you say There But For The Grace Of God Go I may be connected to the legacies of artists and collectives like AA Bronson and General Idea, John Kelly, Gregg Bordwitz, and ACT UP, to name a few? Or does it bring a new perspective to the conversation on HIV/AIDS?

IM: I think the project can be seen as a result of, and a reaction to, their legacies. The artists and collectives you mention come from a place and a time when there was a lot of medical and social ignorance. And a lot of pain, fear, and suffering, especially among gay white men. I’ve only been to about a half dozen funerals in my lifetime; I cannot imagine having to choose between half a dozen conflicting funerals happening during the same weekend. I came into contact with a penis of my own volition for the first time in 1987, when I was 14, in a tea room located in the basement of the Ambassador Hotel in Koreatown/Mid-Wilshire District—the same hotel where Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. That same year AZT was introduced, I “passed” my first HIV test—which enabled me to attain the status of temporary resident of the United States of America. There But For The Grace Of God Go I debuted in 2006, at a time when AZT had been replaced by HAART (highly active antiretroviral treatment) as the preferred method of treatment, and prevention strategies included barrier methods, behavioral interventions, and PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis), with microbicides, PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), and vaccine trials on the horizon. It was also a time when according to Lucia V. Torian, Lisa A. Forgione, Joanna Eavey, Scott Kent, and Yussef Bennani at the New York City Department of Mental Health and Hygiene, “Blacks accounted for 46.3% (142.3/100,000) and Hispanics for 32.2% (91.9/100,000)” of infections that year. Most of whom were “men who had sex with men.” Keep in mind also that this project was very much tailored for the exhibition and the community where the exhibition took place. The exhibition was focused on the effects of Disco on culture. The disco era was also the era of silent transmission of HIV. The Bronx has some of the poorest neighborhoods in NYC, and through no coincidence also has one of the highest rates of HIV and STD incidence. The project is titled after a disco song that includes the lyrics:

“Carlos and Carmen Vidal just had a child

A lovely girl with a crooked smile

Now they gotta split 'cause the Bronx ain't fit

For a kid to grow up in

Let's find a place they say, somewhere far away

With no blacks, no Jews and no gays”

And ends with the missive:

“Sometimes too much love is worse than none at all.”

One of my goals with the project was to start community dialogue in the Bronx about HIV because sometimes a community will stay silent to protect itself, and end up hurting itself even more. A year before the project was first performed, I was working at an AIDS service organization with LGBTQ teenagers in the South Bronx as a sexual health educator focusing on HIV and STI prevention education. The amount of misinformation in the community was truly heartbreaking—from 18 year olds believing they could get HIV from a mosquito bite to hearing about undocumented immigrants paying up to $125 for an HIV test at a private neighborhood clinic in order to keep under the government’s radar. And in some ways, the project was also in response to a lecture I attended when I was a resident at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine two years earlier. When speaking about his work with the collective Gran Fury, the artist Donald Moffett said: “that time is over.” And my initial gut reaction was “well…not exactly…especially in my community.” In retrospect I can see he was really speaking to the end of an era of crisis that has, indeed, passed. HIV is no longer an unknown plague destroying an entire generation in front of our eyes while being ignored by the government. It’s more of a chronic, treatable, medical condition that disproportionately affects Blacks and Latinos and gay and bisexual men. The current government is committed to end it within my lifetime. But the tale sort of remains the same—HIV affects the poor and disenfranchised, so it feels like a never-ending struggle. Especially for those who were present when it first unraveled.

NDE: With Office Hours (OH) in mind how would you say that your work at Longwood might have made visitors, employees, students and professors at Hostos rethink the “safety” of the art space? I read your action as making the world a safer place.

IM: Well, considering the reaction of the Public Safety department at Hostos, HIV is still read as something to be afraid of that needs to be contained, regardless of biological evidence to the contrary. But yes, I also view my action as making the world a safer place—or at least an attempt to make a space safer for an uncomfortable conversation. Which unfortunately can sometimes make a witness to the project uncomfortable. It’s not socially appropriate to talk frankly about the things most important in HIV education: sex and drugs. Until the world is a safe place for those conversations, I guess the project will always feel risky to some.

NDE: How does your work as a social worker and as an artist nurture each other? I am asking this question because the ideas that inform your artistic practice, and also because your acknowledgment of your involvement in these two fields represents a coming-out of some sort. In the art world we are often pushed to hide the non-artistic jobs that help us put food on the table, or keep us grounded in life.

IM: I think my artistic practice has nurtured my work as a social worker and my work as a social worker has helped shape and even informed some of the art that I make. When people first hear about There But For The Grace Of God Go I, they sometimes react negatively—in fact, it came to my attention that the participants at the Whitney Independent Study program had a lively debate about my project the year it was in Do You Think I’m Disco (2006), with many feeling that the project was exploitative. But I think once people find out that I actually was a certified HIV tester and they learn about the diligent steps and care I take in ensuring participants in the project are taken care of as much as possible, in as many ways as possible, it opens up the project to more serious consideration. And people can relax a little and separate me as a person from the project as an experience filtered through the language of art, with real life consequences. I think that’s the trick with conceptual work sometimes. You can’t really appreciate the complexity until you know all the ingredients. Sometimes the two fields come together nicely, like the Play Smart cards I created for Visual AIDS in 2012. It used my homoerotic photographs of Mexican luchadores to spread the message of HIV prevention by focusing on positive self-worth and sexuality for undocumented Mexican immigrants. Early in my career in NYC, I worked freelance art jobs for galleries and museums both as an art handler and as a photographer/videographer. But I often found those jobs disheartening, whether it was because I had to wait 3 months to get paid or I had to bear witness to all the bullshit that goes on behind the scenes in the art world. Talking to adolescents in crisis about their sex lives and drug use comes naturally to me and makes me feel useful as a person as much as projects like There But For The Grace Of God Go I.

NDE: The medical treatments and political responses to HIV and AIDS have been evolving since you presented There But For The Grace Of God Go I. There are new drugs that buy health for those with economic means or living in the “First World.”

The situation is not the same in places like in the Dominican Republic and the “Third World” in general, where health is a luxury reserved for the elite. I recall the image of a HIV positive man selling small vials of Crazy Glue at a private hospital in Santiago, my hometown, in order to buy his medication. How would you respond to this reality as a social worker and as an artist? I can’t help it, but it is in moments like these when I say to myself “to hell with Art.”

IM: As a social worker I face this reality every day. I have had young men come into my office and ask me to list the benefits they will be eligible for if they contract HIV, and have had to explain to them that outside of ADAP (emergency health care that is not really comprehensive health insurance) they do not qualify for any other services as an HIV-positive individual. It isn’t until a person is diagnosed with AIDS that they qualify for things like housing—which is often what these young people are in desperate need of. It’s amazing what a stable roof can do for a person’s peace of mind and heart. I’ve also had young men come into my office and tell me that they’re not taking their HIV medications, but instead selling them on the black market in order to survive. The USA likes to think of itself as developed and advanced, but the reality is somewhere in the USA there is a man selling Crazy Glue to get something he needs too. My response at work is to hold this person, to meet them where they are at, and not where I want them to be; to provide an ear without making faces that betray any kind of judgment; to let the person in front of me know that there’s at least one person in this world who is on their side; and hope the best for them as I walk down 125th Street from the West to the East, without carrying the intense weight of all that sorrow and pain into my home. As an artist I always go back to my first true love: photography. I go back to Lewis Hine, whose work literally changed lives and helped create child labor laws. Art can create change in real ways. There But For The Grace Of God Go I has the potential to save a life. Knowing your HIV status early on and engaging in care has proven to extend the length and quality of people’s lives. Also, because I love art so much, I try and stay positive about things, even if it breaks my heart now and again. Which for me has meant figuring out a way to live a life that allows me to make whatever work I want without depending on the art market or popular opinion. I listened very carefully when my undergrad professors at UCLA kept repeating over and over again: find a way to live that doesn’t involve art. Art feeds very few people in this country. I think for me, it feels good to have a practice and a lifestyle that feels useful.

NDE: If you could present an iteration of There But For The Grace Of God Go I at El Museo del Barrio and as part of Office Hours (OH), how would this look in the scope of a museum-wide initiative not limited to the galleries, and who would it involve?

IM: I actually presented an iteration of There But For The Grace Of God Go I at El Museo del Barrio for The (S) Files 2007 exhibition. These are the images of the project I was able to provide you, since unfortunately documentation of the Longwood iteration was lost due to a failure of technology (external hard drive crashed). It was an amazing experience because I had conversations about the project with almost every strata of the museum hierarchy—from the Director of the Museum to the Education Department to the Museum store to the Security Department. It truly felt like a collaborative experience. That museum has and had some real life angels working there, like Gonzalo Casals and Rocío Aranda-Alvarado. I think the one thing I would change if I could present it again is I would conduct the testing myself. I currently conduct HIV screenings at Streetwork Project, where I manage a community level HIV prevention intervention with and for homeless and runaway gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents. I think it would in some ways truly break down all the walls between life and art. Which is exactly where I feel the most at home.

NDE: Un abrazo and thank you for your time.

New York-based Ivan Monforte was born in Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. He received a B.A. from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1996, and an M.F.A. from New York University in 2004. He attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2004. He has shown at Bronx Museum of the Arts, Longwood Art Gallery, Queens Museum of Art, El Museo del Barrio, Artists Space as part of PERFORMA05, Elizabeth Foundation Gallery, Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, La MaMa Galleria, and Socrates Sculpture Park. He is the recipient of a UCLA Art Council Award, a Lambent Fellowship in the Arts from the Tides Foundation, and an Art Matters grant for research in Samoa. He has participated in residencies at Sidestreet Projects, Lower East Side Print Shop, Smack Mellon, and Center for Book Arts. Ivan uses conceptual strategies to explore themes of race, class, gender, stigma, and the pursuit of love. Their work often complicates the lines between art, activism, and lived experience through social sculptures, performance, video, photography, and tattooing.

Further information about Ivan's work here.

This Q&A was first published with Visual AIDS on January 15, 2015 (HERE)

Images above courtesy of Ivan Monforte and Elizabeth Foundation Project Space