Jennifer Zackin

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo: Jen, it has been two decades since we met at The Bronx Museum as part of the Artists in the Marketplace (AIM) program. So much rain and snow has fallen since then and I do not mean in a chronological way, but more in terms of where we both stand creatively. I don’t think we are anymore the youngsters looking to flirt with the art world. I am not. The page is all yours, tell me!

Jennifer Zackin: Indeed we’ve made a lot of snow angels. Thank you for inviting me Nicolás, it is an honor to be part of the Interior Beauty Salon.

NDERE: I remember the mandalas that you were giving shape to in 2001, with myriads of colored plastic soldiers. We lost touch at some point and then I found you invested in healing. The first word that comes to my mind is Despacho, offering. Can you walk me from this hiatus in our relationship and where we picked up again from the standpoint of your art practice?

JZ: The work I presented at our AIM exhibition at the Bronx Museum in 2001 is titled The Divine Fortune, a floor piece pattern work I developed in 2000 while at a residency in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, in Southern India.

I went to India after graduate school in a DIY postgraduate program to explore ideas, principles and practices in spirituality, magic and activism. I was so curious about my inspiration, how it works and where it comes from. Six months felt like a lifetime full of animated experiences that all flowed in synchronicity. One of the first cities I visited was Jaipur. Just by walking the streets of Jaipur I found an entire animal kingdom: cows, birds, dogs, cats, rats, pigs, goats, horses, elephants, camels, donkeys, monkeys and more. After these walks I slept for the rest of the day. The stimulation was fierce. Once I got into the flow I had incredible experiences, such as traveling with Dr. Arun Gandhi following his grandfather’s legacy visiting communities, sites and institutions related to the life and non-violent work of M.K. Gandhi.

One of the central reasons I traveled to India was to experience the painted temples in Tamil Nadu. Intuitively I knew I needed to physically engage with the matrix that symbolizes everything from a grain of sand to the cosmos. The Hindu and Buddhist temples allowed me to have a whole body somatic experience inside the Mandala. Prior to visiting these temples my only experience of the mandala was on the page. I became a temple junkie while traveling. Already immersed in pattern by studying the symbolic languages found in textiles and architecture, I was using manufactured objects—mainly plastic figures—grouping them in sequential arrangements. I began this particular pattern series by creating a prayer rug with square and circular Little Debbie cakes arranged into a patterned prayer rug made of processed foods. Aside from the delicate brown palette, the most impressive element about it was the sugary smell of manufactured sweetness.

Before traveling to India as a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute, I acquired a vintage fluorescent-colored set of plastic cowboys figures from my favorite vintage toy store in Chicago “Uncle Fun”.

I took the pattern developed in Thiruvananthapuram, arranged the plastic fluorescent cowboys and embedded it into clear rubber. There was an element of magic when the fluorescent cowboys exactly matched the color palette of the Hindu deities Lakshmi and Shiva. I became enamored by the power of the people’s devotion to Lakshmi and Shiva while working on the design in Trivandrum. I created the pattern using the form of Lakshmi, goddess of wealth, fortune, power, luxury, beauty, fertility, and auspiciousness. She holds the promise of material fulfillment and contentment. I juxtaposed Lakshmi with Shiva who is the ultimate god of goodness and benevolence, and serves as the Protector. Shiva is also associated with time, particularly as the destroyer of all things. These are all attributes my Indian friends believed the USA held for them. The Divine Fortune is a flawed impression akin to Hollywood’s notion of the “cowboy and Indian”.

The first time I was introduced to the traditional Andean Despacho Ceremony I was mesmerized by it. It was at the summer solstice ceremony in 2001 at the same time the The Divine Fortune was included in the AIM exhibition at the Bronx Museum. A Despacho Ceremony is a ritual offering meant to nourish the natural world and protect the human world and strengthen harmony, reciprocity and reverence for Pachamama (motherland/female) and the Apus (mountains/male). Andean Priests perform the Despacho Ceremony as keepers of the ancient knowledge of the natural world. The Despacho is central to Andean beliefs and represents a microcosm of every aspect of life in the Andes.

The connections between the Himalayas and the Andes are endless. The most fascinating for me is their energetic connection. In the 1960s the Dalai Lama held a special ceremony to transfer the energy from the Himalayas to the Andes in order to protect it from the Chinese. The Himalayas are thought to hold a male energy, while the Andes are thought to hold a female energy.

NDERE: How and why did you get immersed in healing? Would you mind sharing any personal story that might illuminate this path?

JZ: Wow, Nicolás, the eternal peeling of the onion, it's a never ending story. Art was my salvation growing up. I was invited to be in the talented and gifted program in middle school. My child and teenage years were rough and the art room was a place I found refuge. In my early 20s I made the conscious decision to begin healing. I started working with a counselor after realizing I was completely shut down to any sense of feeling. The counselor I was working with in 1994 while living in NYC and going to the New School encouraged me to go to a weekend workshop with Julia Cameron. She was teaching about her book The Artist’s Way. I most certainly experienced an awakening while working with Sonia Choquette, one of the facilitators and author of the book Psychic Pathway. Four years later while living in Chicago I remembered Sonia lived in Chicago. I signed up for a session with Sonia and we met in February of 1998. She told me everything that was going to happen to me later that year including my acceptance into the Skowhegan School in Maine. She advised me to work with a counselor in Chicago who used shamanic and talking techniques in her practice. I also worked with her husband who practiced cranial sacral therapy. He recommended a medical intuitive friend in NYC. Once we met in New York this healer invited me to a Summer Solstice ceremony at Bear Mountain with her teacher Don Oscar Miro-Quesada Solevo, a respected kamasqa curandero originally from Peru. It was at this solstice celebration that I first discovered the Despacho Ceremony. A few months later I was on my way to Lima to be in an exhibition and to explore Cusco, Machu Picchu, Puno and Lake Titicaca.

When I was living in Cusco I worked with healers and herbalists. One thing I loved immediately about Cusco is how everyone has a medicinal herbal garden. If I had any sort of ailment I’d be offered an herbal infused tea using the medicinal plants in their garden.

At 18 I was diagnosed with PCOS. I used western medicine for a while, but after going to Peru I started working solely with the plants. The primary maestro I worked with was Don Ignacio, famed ayahuasquero from the village of Infierno outside Puerto Maldonado, a cowboy town in the jungle at the edge of the Andes. Infierno was one of the first indigenous communities to settle in the Puerto Maldonado area on the Tambopata, a coffee-colored river that meets up with the Madre de Dios river. Both rivers flow down from the Andes. This area in the Manu park region is known to be one of the most bio-diverse areas in all of the Amazon Rainforest.

Don Ignacio was a world renowned and respected maestro de las plantas, master of the plants. Any one who showed up to Don Ignacio’s humble rainforest home found out about him by word of mouth. On any given night the ceremonies would consist of locals, nationals and/or foreigners from all over the world. It was in the early 2000s, way before the mad commodification of mystical tourism. Mystical tourism was happening but not to the degree it happens now. Nowadays the industry is saturated with foreigners who are running the centers and serving the medicine.

I was very fortunate to visit Don Ignacio multiple times and make dietas, plant medicines, with him. We worked with the master plants abuta and her sister ayahuasca. Abuta is a plant traditionally used in South America and Africa to heal the female reproductive system. It is not used ceremonially like ayahuasca. I have no words to express how deeply grateful I am to Don Ignacio for his openness and kindness to share his medicine, his life, his land, his plants and his family with me. Two of my favorite things about sleeping in Infierno were listening to the sounds of the capybara at night and waking up at 4am to the crowing of roosters who were having super loud crazy conversations with each other throughout the village.

I found this influenced my artwork and in 2004 I made a stop action video of the construction of a Despacho titled I Have. Dream. I showed the video to Don Mariano who is a pampamaysayoq, another renowned maestro. He liked it and after that invited me to become his pupil with my partner at the time and now husband Adolfo Ibañez Ayerve. Adolfo was part of a community of artists I was spending time with in Cusco. I never dreamed I’d meet my husband in Cusco. He says I went to Peru looking for him. In 2007 we married. In 2005 Adolfo traveled to the USA for a kid to kid cultural exchange program working with street and market children in Cusco and with a group of children in Peekskill, NY. The Katonah Museum Education department sponsored the project. Another video I made with Adolfo during the years we were apprenticing with Don Mariano is ayni=reciprocidad. In this video we were attempting to delineate the traditional and cultural attributes of the DespachoCeremony. Over the years we’ve continued spending time, learning and making despachos with Don Mariano.

As soon as it is safe to travel Don Mariano is planning a trip to visit us in the Hudson Valley to share his teachings at my studio. He’s feeling an urgency right now to share his knowledge. Everyone is invited. We will be posting information on our Chokechaka project page once we can gather again.

NDERE: I would say that you have been at the forefront of a marked interest in the arts in healing. You were going to Peru as a creative and collaborating with shamans and healers way before this became a point of interest in the arts. And you took risks that may have pushed people like Benjamin Genocchio to write a piece for the New York Times such as The Artist’s Tribe. I am listening.

JZ: Thank you, Nicolás, I so appreciate the opportunity to speak about that complicated moment. That review in the New York Times really touched a nerve for me. Issues around colonization and cultural appropriation are of vital importance; if underlying systems of oppression are to be shifted, these issues must be a major concern for anyone working in the realm of cultural exchange. Those who do this kind of work need to constantly examine and re-examine ourselves and our own culturally-constructed biases. In this case I felt the reviewer lobbed generic attacks by stating the work was “exploitative of the relationship between Western artists and intellectuals, and indigenous communities” without looking deeply into the work he was critiquing. If he had, he would have understood that my interests are genuine and my relationships real. I cherish my friendships and relations in Peru, each of which has its own special rhythm and connection that has been nurtured for almost 20 years.

I’d like to share a few stories about my life and work in Peru, particularly with regard to collaborations with people from the Q’ero nacion:

As for how it all began…on the plane ride home from Cusco after a month-long visit in 2003 I had a very strong premonition I’d be returning to Cusco to live for an extended time with the intention of creating a new body of work. Within six months I returned to live in Cusco. With a friend I rented a house on Calle Márquez, in the center of the city, next to the main plazas. The day I arrived a group of people from the Q’ero nation whom I’d befriended on my previous visit opened the door and welcomed me to my new home. This was the most magical welcome. I went back to Cusco specifically with hopes of working with this community, and had no idea my new friends would be waiting for me in Cusco upon my arrival. This is but one sweet story among many that convey the way that my work and life has been guided by synchronicity.

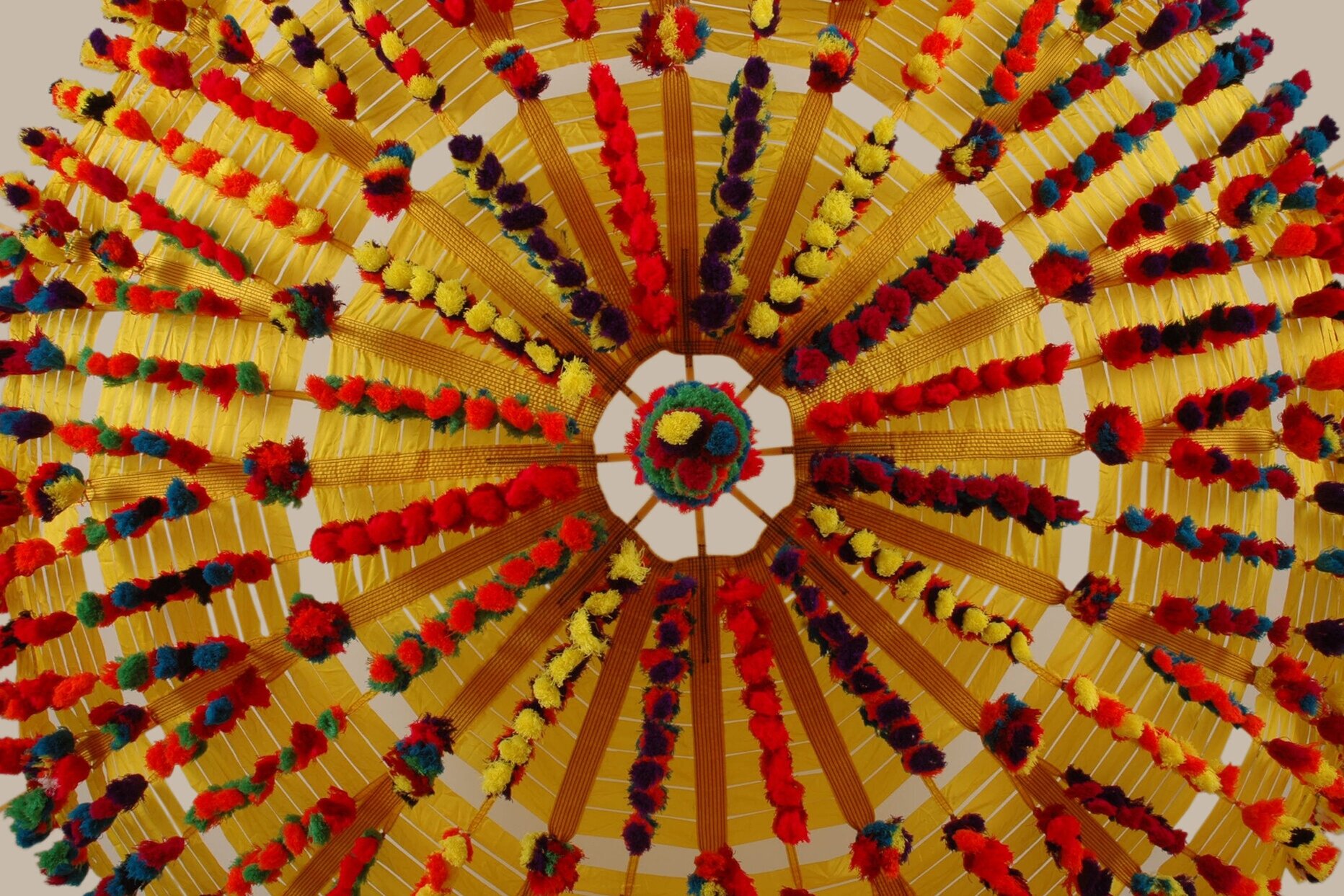

My Q’ero friends and I created an installation together titled Hanaqpacha Intiq Sombran. We transformed a yellow webbed U.S. Army parachute into Inti - the Incan sun god. I bought the parachute in an army navy store on 8th street in New York City. The parachute is used to aid in plane landings on aircraft carriers. My collaborators made over 1000 multicolored pom poms that traditionally go on their intricate knitted and beaded ch’ullo hats. The Q’ero skills are vast and magnificent! We created a pattern playing with the color and variation of the pom poms and attached them to the parachute (the piece is intended to hang from the ceiling and with the viewer standing underneath, looking up at the pom poms). Without speaking a common verbal language, we were playful in our methods of communicating. In the end, my friends absolutely loved the work because the large yellow parachute is the sun “INTI”. Don Mariano, the elder of the group and one of my most treasured friends and teachers, titled the work Hanaqpacha Intiq Sombran, Heaven/Earth, Sun, Spirit. The work we made together was presented in an exhibition at ICPNA in Cusco. It was awesome! My five collaborators trekked down from their village for the opening through a huge snowstorm. In 2004 we spent a great deal of time together in/around Cusco, including visits to the Q’ero Nacion in the high Andes.

Our relationship continues to grow based on mutual admiration and respect. We have become an intercultural and intergenerational group of friends, now considered family, who continue to create and learn together.

NDERE: I experienced a situation in a panel in Catalonia where, every time I opened my mouth to explain what I was doing in the arts with the subject of pilgrimages, the deeper I found myself misunderstood. I ended up writing a piece published by IDENSITAT that allowed me to talk again and clarify things. Is there anything that you would like to bring forward in regards to Genocchio’s article?

JZ: I want to take a moment to express utmost gratitude to my beloved husband, extended family and my collaborators from the Q’ero Nacion Mariano Quispe Flores, Santiago Quispe Qhapaq, Benito Apaza Lunasco, Lorenzo Qhapaq Apaza, and Nicolás Flores Apaza in Peru. It has been through the generosity of these individuals in particular that I have learned so much about the richness and intricacies of the highland and Q’ero cultures. Seventeen years ago when we visited the remote Q’ero villages, it took 3 days to get there; one day traveling by bus and two days walking in extreme altitude. I was so fortunate for the opportunity to experience the Q’ero culture in much the same way it had been for the previous century.

More recently many Q’ero people have moved down to Cusco to give their children an opportunity for a more conventional education. While Peru tried to set up schools in the remote villages, teachers tended not to show up due to the isolation. For Q’ero families, life in Cusco can be rough. Most are totally dependent on the tourist industry, and are suffering tremendously right now during the pandemic with no means of income. We are supportive in whatever way we can be. Currently we are seeking ways to help our friends reach broader audiences for their work using our web skills and social media channels. The Q’ero kids are becoming less interested in ceremonies and traditions. They want to be taxi drivers and pop stars.

NDERE: You took clear steps that might have been counter to a career in the arts. Gosh! The word career makes me think of running after something all of the time. Truth is, that I think that you, me, and many others were trained to be part of that race. But some of us dropped out of it. You moved outside New York City, got married, and seem to be doing what you want rather than what you were told to do, professionally. Can you talk about this?

JZ: The Artist In the Marketplace seminar was the starting line for me in that race. I was just moving back to New York City. I was on a mission to attain solid footing in the art world. Graduate school and AIM pushed us to establish ourselves in the art market. I was busy participating in museum shows, fellowships, commissions and residencies. By the end of the 2000s I was burned out in NYC and needed a serious reboot. I didn’t grow up in the city. I grew up in New England among the trees. I desperately needed to retreat back into the trees. Adolfo and I moved up to the Hudson Valley. It took time to unravel. I never stopped working. I’ve established a method of working where I am initiating social sculptures based on my installation work. It allows me time to be in the studio by myself and time to work in the public realm communally. Both work modalities are intrinsic to my practice. Currently I am working on a series of Vortex Weaving. I wove a 10 ft vortex on a loom installed in a 10 ft square space using 2,880 ft of rope. Mathematically speaking, a torus is a three-dimensional ring or doughnut shaped-object around which energy can flow. As it spins, a vortex forms through its central axis. This pattern can be found throughout the universe in hurricanes, galaxies, and atoms. I began Vortex Weaving. with groups of people before covidSince the pandemic began the communal work is on hold and will resume once we can gather again.

NDERE: Can we talk dirty, as Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens might say to refer to Earth matters? What is your commitment to the Mother or the Lover, meaning the planet on which we live? Can you answer this in relationship to what you do creatively?

JZ: An important principle in my work is working in partnership with nature to forever strengthen our fragile connection. One of the most inspiring elements I experienced in the highland cultures of South America and Asia is people's ability to live in total synchronicity with the natural world. Irresponsible caretaking of this planet is the root of so many social, political & environmental issues. Just think about the archaic industry of oil and mineral extraction. Where does this type of thinking come from that we can extract organic material from the earth and there are no consequences? Climate change is a definitive ultimatum to clean up our act if we want to continue living on this spaceship we call earth.

In 2002 I was awarded an emerging artist fellowship at Socrates Sculpture Park for a project entitled Pachakuteq. This award was my first opportunity to work outdoors in a public space. I loved the experience. I wrapped the grove of trees in the center of the park with 3 miles of rope with the help of an army of volunteers. We leveled a striped pattern between 18” to 90”of each tree. Visually I wanted the pattern to continue through the negative space between the trees, so when the viewer stood back from the work the lines connected from tree to tree, highlighting our connection with each other and nature. Two more tree wrapping projects were commissioned in 2005, one for a Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) exhibition on Governors Island entitled Taps, and another at the Katonah Museum entitled OHMy to honor the museum’s 50-year anniversary. The tree wrapping series is designed to be installed in the cooler months of the year when the trees are dormant and taken down before the Spring equinox. I’ve been creating outdoor public art projects ever since the Socrates Sculpture Park fellowship (Thank you, Socrates Sculpture Park!).

La Ofrenda, a work celebrating the offering process, was created at the Berkshire Botanical Gardens and commissioned by MASSMoCA for the Cultivate/Badlands Exhibition. I created an offering station planted with vines, so by the end of the exhibition the armature of the piece was robustly covered with medicinal plants. In strategically placed “pockets” built into the structure I placed shells and colored stones and invited guests to offer the objects to a large stone sculpture (also known as an apacheta or cairn) built next to the offering station.

AfterShock is a site-specific grouping of “Marine Life Saving Pillows” designed to save marine life by absorbing oil after spills. The cluster of over 200 Marine Life Saving Pillows made from brightly colored tights stuffed with sheep’s wool and covered in orange mesh. The piece creates an extravaganza of color, like a giant sea anemone. The technique used in the making of the piece was inspired by oil absorbent "hair booms" fabricated by Matter of Trust to collect oil during the Deepwater Horizon disaster. AfterShock was commissioned for the 2010 Dumbo Arts Festival to raise awareness about the ongoing detrimental effects of the oil industry, the perilous state of our oceans and the life they contain, and the negative consequences of social and economic structures based on consumption of fossil fuels.

In 2011 I participated in a Permaculture Design class with the idea of incorporating permaculture principles into my art and life. We were just moving onto land we acquired in the Hudson Valley. I found many symbiotic connections between permaculture practices and the practices I encountered while living in Peru. The next two projects I executed after the permaculture class were collaborations with the earth. I made The Earth Tattoo, part of my offering series. It's an offering ceremony using seeds and soil to create a pattern using the permaculture sheet mulching techniques. Over time the “tattoo” produces fertile soil and is used for a garden. At a Bioneers gathering I created an Earth Tattoo that was composed of 100lbs of soil, 20lbs of corn (yellow), oats (white) and milo (brown). These three elements formed a Triple Crescent Moon Symbol.

The following year I made the Earth Tattoo into an art and soil building social sculpture called

Re Seed Saugerties. I collaborated with a local landowner and with this opportunity we built a community around a 70’ x 100’ corner lot in the village of Saugerties. On this piece of land we built soil using a Permaculture sheet-mulching system, a no dig technique involving layering organic materials to mimic the natural soil-building process found in forests. We constructed an Earth Tattoo, shared food, created seed sculptures and Chicken Danced.

We hosted over a dozen public gatherings including….

- Sheet mulching parties and planting nitrogen fixing plants with the Boys and Girls Club

- Seed and Food Shares with the Long Spoon Collective

- Seed Sculpture Labs with Adam Zaretsky

- Oath of Growth, I am the Keeper of Smallest Plant action with Carrie Dashow

- Seven Chicken Dance-arama’s with Linda Mary Montano

- Two community offering ceremonies with Adolfo Ibañez Ayerve

Five years after the initial soil building year Re Seed Saugerties is currently a learning garden used by the Saugerties Boys and Girls Club and facilitated by the Underground Center.

NDERE: We are coming to an end with this Q&I. Maybe not, if we think that there are not really endings, but that all movements (dance included!) continue to reverberate on and on… Can you come to a halt, take a long and gentle conscious breath in, and a long and gentle conscious breath out, and tell me/us what ultimately matters to you?

JZ:

Being

in Relationship.

in Love.

in Flow.

in Nature.

in Ayni. (“reciprocity” in the Quechua language)

a Vessel.

a Vortex.

Vigilant.

Present.

Thank You Nicolas for your tireless inspiring healing art life!

Jennifer Zackin’s related links website / instagram / Re Seed Saugerties / Chokechaka

All of the images above represent works by Jennifer Zackin and are courtesy of the artist.

Jennifer Zackin says “Thank you” to": Adolfo Ibañez Ayerve, Alyce Santoro, Linda Mary Montano, Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo, Mariano Quispe Flores, Santiago Quispe Qhapaq, Benito Apaza Lunasco, Lorenzo Qhapaq Apaza, Nicolás Flores Apaza, and Ignacio Duri Palomeque

For the last 20 years Jennifer Zackin has been integrating public art, sculpture, installation, performance, collaboration, ceremony, photography, video, collage and drawing into acts of reverence and reciprocity. Whether wrapping trees in patterns of brightly colored rope, growing medicinal herbs in a public garden for public use, offering large masses of rose petals to oceans and lakes, creating absorbent tentacles ("hair booms") out of salvaged materials to aid in the clean-up efforts of toxic spills, Zackin seeks to engage and create community in her process, bringing art and ritual into everyday life. Every act is an exploration of exchange, communion, performance, skill-sharing and mark-making.

Writing in a cataloque essay about her work Lori Waxman states; “Jennifer Zackin has worked with Rose Petals, Little Plastic Cowboys, pre-Columbian symbols, bright handmade pom-poms, cheap mass-produced posters, coca leaves, and her grandfathers old Super-8 home movies. How she weaves them into rhythmic, often meditative forms depends in great part on the underlying pattern that she is able to detect and orchestrate among her diverse materials.”

Her work has been exhibited in national and international museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art NY, Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art CT, Spertus Museum - Chicago IL, Rose Museum MA, the Wexner Center for the Arts OH, Contemporary Art Museum - Houston TX, The Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden - Norway, Institute of Contemporary Art - Boston MA and the Zacheta National Art Gallery - Warsaw, Poland. Commissions include Governors Island NYC with LMCC, Katonah Art Museum NY, Socrates Sculpture Park LIC - Queens NY and the Berkshire Botanical Gardens - Stockbridge, MA. She is the recipient of fellowships and residencies, including Factory Direct at Pinchbeck Rose Farm, Art Omi, Atlantic Center for the Arts and the Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture.