Laura James

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo: I am elated to get to converse with you, Laura. It is not usual for me to be in dialogue with a guest with whom I can talk about the Caribbean, theology, creativity, and The Bronx in one place! Thank you for the “yes” to this Q&I.

Laura James: Ha! Yes Nicolás, thank you so much for inviting me. I must say, ever since we did that talk together at the Allentown Museum, I've just been that much more impressed with you and your vision. Before that I didn’t know you had such a strong connection to theology and religion, so it was really interesting to learn about those aspects of your work during your talk. So yeah, thank you, I appreciate the opportunity to speak with you today.

NDERE: Before we move forward into the complexities behind your work, can you introduce me to the theology shaping Ethiopian iconography as it pertains to orthodox Christianity? I am asking because of my specific understanding of the icon in Catholicism as an entry point into the Divine and my limited familiarity with this in the orthodox context.

LJ: OK, so Ethiopia has been a Christian country since the 4th century when the king was converted by two European missionaries who were shipwrecked there. Many of the pictures that the Ethiopian Christians saw early on were images from Europe, so there were lots of Marys and Crucifixion scenes, and the early art of Ethiopia is strongly connected to that European tradition.

NDERE: How did you get involved with the work that you do? I know of your illustrations of the Book of the Gospels. It is rare to see creatives who allow their spiritual selves to be out in public.

LJ: So, I like to say that I fell into being an artist. Honestly, I believe I was an artist in a past life, so I had I hardly had a choice but to do art this time around. It's sort of a long story… I went to church with my family growing up; a Brethren church. There were no images on the walls, and we were not allowed to picture Bible characters, but we had children's Bibles with all kinds of weird and fantastical images. One of which was the image of “white Jesus”—with ridiculously blonde hair and blue eyes, looking like, you know, sort of like a superhero or just some kind of alien creature, distinct from everyone else in the picture. So, I was confused by the Bible, because I could see that Jesus was so very different than me and everybody else in our church. He was just so outside of us I wasn't really sure how to reconcile that.

In any case, when I was about 18, I was walking around in my neighborhood in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, and I saw this book called Ethiopian Magic Scrolls in a botánica on Fulton Street ((the store is still there, by the way). I was really attracted to the book and thought that the images looked kind of easy, like I could paint them. I hadn't really painted much at this time, I was more into photography, but having gone to church for 17 years of my life with white Jesus and then seeing these black angels, I was really intrigued. I bought the book and it said that the images in it were copied from “time immemorial” by laymen connected with the church, so I figured I would just copy them and continue the tradition! I did copy what I saw there, but very quickly, within the first couple of months I started to make my own paintings. We lived in a brownstone in Bed-Stuy, with great big walls and I just sort of went crazy making huge paintings of Biblical stories.

Everyone in my paintings were black, so I guess that was a radical part. You say it is rare for creatives to allow their spiritual selves to be out in public…I really had no concept of the “art world” or anything like that. I wasn’t thinking about trying to sell my work and be an artist. Early on, there were people who really appreciated the work, who wanted to show the work, who wanted to buy the work, so I knew I was on to something.

I had been told repeatedly that I would never get “into the art world” doing religious work because that just wasn't done (meanwhile, the MET is filled with icons). I didn't know how to reconcile that, but you know, it is what it is. This is just my work; this is what I have been called to do. I do have a secular style as well, so I also paint other things; I have made paintings about slavery, and nannies, I paint women. I do have the other style, but I also really enjoy painting sacred images and icons from The Bible and also from other religious traditions. I like to imagine these stories in my head and to put them down on canvas.

NDERE: I am trained as an artist as well as a theologian. I had the fortune to study at Union Theological Seminary in New York, a pioneering place in regards to free thinking. The conversations that we had at Union would never happen, I think, even in the most progressive art milieus. I remember being in a class where our professor asked us if angels had gender. Can you talk about activism as it deals with gender, sexuality, race and class in the icons that you bring forth? Can you talk about angels too? I have become enamored of these beings thanks to my dear friend and mentor Linda Mary Montano, who loves angels.

LJ: Well, I'm hardly a theologian! I actually worked with Union Theological Seminary in the past. I was a teaching artist there for a semester, and I've had a few solo exhibits there. I love Union, free thinkers as you say, and you know, willing to be human—not just trying to follow the Bible blindly, but to question as well.

I like to paint angels. I have a whole series of guardian angels and I also like to paint women with wings. I have a relationship with the Orishas, who could be thought of as angels, and I do believe that we all have guides and angels around us who help us navigate this Earth plane, and the stresses and the pressures of this human experience.

When you talk about activism, I definitely think of myself as an activist in terms of my desire to bring about social change, and just change in general. I think it's really important that we do something about the things we see are not right, and to call out the bullshit when we see it.

I'm interested in honoring women in my Biblical paintings, and just to show Biblical figures as black and not just as white people, is sort of a radical thing!

Like I said, Ethiopia has been a Christian country since the 4th century and there has been a long history of Christianity in Africa. I do believe that the Bible in particular and organized religion is more about controlling people than about spirituality and uplifting people. It is not possible to ‘follow’ all the rules in the Bible—but one that I like, that Jesus said over and over is “love one another.”

NDERE: I am blessed to have had as teachers some of the brightest brains-hearts in theology, from James Cone and his Black Liberation Theology, to Daisy P. Machado and her work of love in the Mexican- U.S. Borderlands, and to Roger Height and his passion for an unhindered inquiry of religion, which actually made him a dangerous character according to the Vatican. My teachers had no pelos en la lengua, no hairs on their tongues, as we would say in Spanish. They said what needed and had to be said. Your language is a visual one, how would you say this speaks face-to-face to the evils of our times: racism, sexism, ageism, speciesism, empire…?

LJ: Well, I have always believed in speaking the truth. I’m a second-generation American, my parents are from Antigua… we're known there for telling it how it is! Not mincing words, and you know, try to make ugly things look pretty. I guess with my art, I actually do try to make everything pretty. When you look at my paintings, I want you to see something beautiful that you want to investigate and look at further but, when you look closer you do see the real story. For instance, you see the little child in the wall or floor whose mother is a nanny for some other kids in another country.

I'm very interested in showing women as equal and prominent people in our society, I mean, duh. How far are we going to get without women? And, hey I'm a woman so I paint what I know. I paint mothers and the stories of the women that I know.

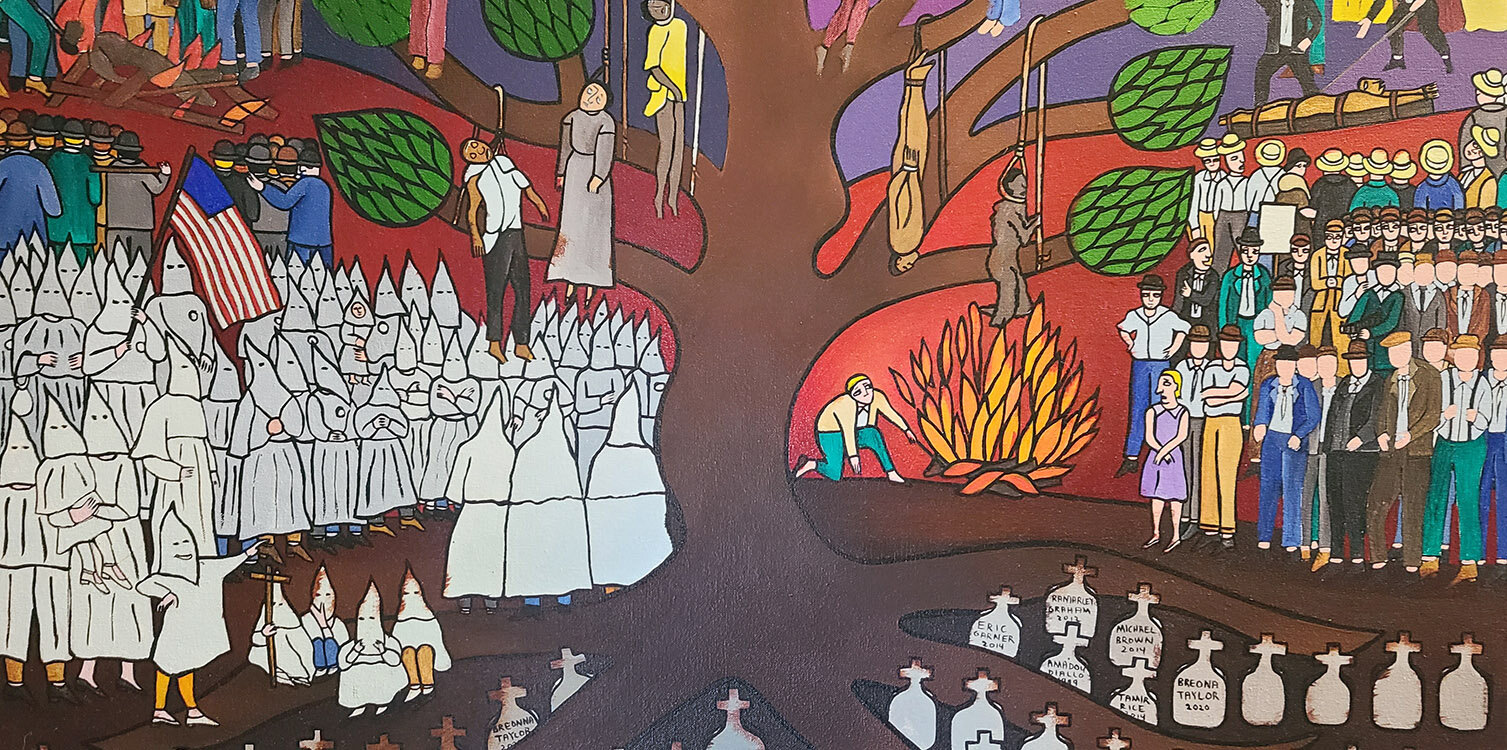

I'm working on a series now called Race and Reparations, where in 10 paintings I will show why reparations are justified, why the need for reparations. (They can argue about how, I’m concerned with why). There are many reasons why reparations are just, it is a no brainer to me. Many of the subjects I’m interested in are things people want to pretend don't exist, like the nanny doesn't exist outside of her job—I mean, there are millions of nannies, their work is important, we should honor them and lift them up because they're raising the children.

A lot of my work speaks to things that we do not want to see or hear, but I want to make people see.

NDERE: I am not big on the Bible because I find some of it to be quite problematic. However, I am not as radical as Mary Daly. In any case, I am aware of the curation that went into the putting together of this book and the key writings that might have been left out because they would “mess things up,” theologically speaking. The Bible is missing the voices of women or views that might have not been cohesive with what we ended up with. Have you done any work with the Gospel of Judas and The Gospel of Mary of Magdala? Have you thought about illustrating The Woman’s Bible by Elizabeth Cady Stanton?

LJ: So, I'm not a super fan of the Bible in the way that it is written, it is a book that was written to control people. I think that we can probably all agree on that at this point, whether you think it is controlling for good or for bad, it’s a book that can be interpreted in a million ways, so you know it’s going to be problematic. I actually stopped painting Bible stories at one point because I was so conflicted about promoting some of the ideas that were found there, but I started again because I was moved by people who would write to me and express their gratitude for being able to see images of the Biblical characters that aren't white.

As a child growing up, seeing white Jesus in our children’s Bibles, and on TV, and other places, it really was offensive to me…so being a part of the change in this type of imagery was something I ultimately felt I wanted to do. And not for nothing, I am a painter, you know, I like to paint! I especially like to tell stories with my work, and the Bible is full of interesting stories with fantastic imagery. I also like to paint stories from other sacred traditions, most sacred stories are rich with wonderful imagery.

Right now, I have two commissions in particular that are trying to change current acceptable narratives. I am making a series of four paintings for a progressive Catholic Church out of Ohio, the paintings are based on Mary Magdalene's story as written in the Bible, not the subsequent writings about her as the “penitent whore,” you know, the made-up story about her. These paintings are based on the actual writing about her in the gospels where she is the first to encounter Jesus after the crucifixion, where he tells her to tell the other disciples that he is risen, making her the “apostle to the apostles.”

I've also been commissioned to paint a crucifix for the University of the South in Tennessee. The cross has been cut into the shape of an Ethiopian cross and Jesus, of course, is black. The piece will be installed in a chapel on the school's campus. This school was actually started by slave traders, and slave owners back in the 1850s, so for them to have the courage and the insight to commission me to do this work is quite an honor for me. I’m very pleased to take on this kind of work, especially considering the kinds of images I grew up seeing in church. I work mostly on commission, so I probably wouldn’t take on a job like illustrating The Woman’s Bible unless someone hired me to do it!

NDERE: What does the word sacred mean to you in connection to your work and personally? I am asking because all art had once a scared function? Also, how does the sacred might speak to activism?

LJ: Well, anything sacred is connected to God, or we can say Source. We are all here right now living this human experience, trying to get along with one another. These days, we're able to learn and know more things faster and deeper, and to really make an impact on what's going on here on Earth. I feel like my work is helping to uplift people- which is a sacred act.

I would say I have a God-given talent, especially being self-taught, and actually, you know, I got good at painting pretty quickly. I’ve always felt that my work was divinely inspired, and I feel blessed to be able to do something I love, that’s meaningful, to be able to make a living and to also give back to my community.

Whether its paintings based on themes from sacred traditions, or honoring workers, or slavery and race, I want my work to bring awareness to subjects that are often hidden. I want my work to elevate people’s consciousness, to inspire people to do better, to be better. Many people are raising their vibrations at this time, and honestly if we were to continue with the low energy path on this planet—with the abuse of the Earth, racism, unfair laws and greed—we’d fall over the side of the cliff, and we can't let that happen. In terms of activism and trying to bring about positive changes in society, I do hope that my work does that.

NDERE: I could talk theology until the angels come home! But, can we discuss The Bronx and The Bronx200, the endeavor bringing together artists from our borough, and which you have organized. You are connected to the Caribbean, the place where I left my umbilical cord buried, as my friend Josué Gómez would say. This is also the navel of the world, the vortex where all continents converged in ways that have not happened in any other place on the planet. You were raised in Brooklyn and then found your way to The Bronx. I do not have a question, but I am intrigued by your story…

LJ: You do not have a question! OK, well I will tell you a little bit of the story, it’s a story I've told many times. I illustrated a children's book and when it came in the mail, the back of the book said “she lives and works in The Bronx,” and I was like, “Oh shit, I live in The Bronx!” I’d been here for eight years by then, but I didn’t know anybody here—I live across the street from the subway so I would just go back to Brooklyn or Manhattan to see my friends.

Really, I wanted to have a nice big party and meet some artists, but I didn't know any artists in The Bronx. I asked one artist I knew with a connection to the Bronx, although she lived in New Rochelle, Valeri Larko, if she would help me put together a list of artists. Long story short, it turned into this database of 200 Bronx-based artists.

I did want to meet people in person, and to have events and things like this, and we did have a great big launch party for the site at The Bronx Museum, but it was also an intriguing idea to put something online where people could just go and see the art of Bronx-based artists and contact them directly for projects or other inquiries.

The Bronx is a big place and artists are really spread all over the borough. There’s really no central art hub, although now I guess they’re trying to do that with Mott Haven, but six years ago there really wasn't anything centralized and it seemed like a good project.

We’re in the process of revamping the website right now so it's going to have a whole new look, with new artist and new pictures.

I'm interested in community building. I see myself as someone who connects people, my friends say I’m “a connector.” I will meet someone and say, “Oh what do you do?” and then think “Oh, I know somebody who you should meet.” I’ve been doing that for many years. I figure we could all use a little help, and I have personally benefitted from collaborating, and making connections. I’m happy to facilitate the directory, we’re supporting artists and that makes me feel good.

NDERE: Last night I had a dream in which I went to give a presentation to a group connected through clay: ceramicists and potters. When my talk concluded I asked attendees: “What does your work do for you?” There was no linear response, instead, the group started to sing a traditional Jewish song to me. I was moved by this performative act. I left the space in silence. When I woke up, I asked myself: “What does my work do for me?” I am asking you now. “What does your work do for you?”

LJ: You have such an interesting mind, Nicolás. I really appreciate the way that your mind works. I find you to be a very honest person, and I appreciate that. As for what my work does for me, well, it is my life. My work is my life, I've doing been this now ever since I was 18, it's the only job I've had, it's the only thing I know. Like I said, I feel very blessed to be able to do this work, to be my own boss and to make my own way. I think sometimes what I would do if I weren’t doing art, and I can never think of an alternative, because I am just an artist, and I make art! That's it, that's what I do. I am really pleased with the way things are going now, to have interesting projects to work on, to feel the respect of people who appreciate my work. My art is wrapped up with my spirituality, with my family, with my world.

And I am grateful, gratitude is a big thing for me. My work sustains me in many ways, you know, gives me money so that I can buy things and pay my bills, which is an important thing here on Earth. It also gives me peace of mind and it’s a creative outlet that allows me to show those things that are in my head to the world. Also, to teach people, and to get my point across, and to hopefully inspire. My work is everything to me, is my life but not in the kind of way where it drags me down or holds me back; it uplifts me.

NDERE: Any closing words?

LJ: Well, I would just say thank you again for inviting me to speak with you here on this platform. I admire the fact that you take time to do this project, obviously dear to your heart and I am sure this work uplifts you in many ways; so, thank you for allowing me to share this space with you and to talk to your community. I've always liked the saying “be the change you want to see in the world” and I strive to do that, and I guess my final words would be to everyone, “Hey! Be the change you want to see in the world! We can't wait for ‘people’ to do something, we have to do it. We must be the people who recognize that there is a problem, that there is an issue, that there is a ‘thing’ that needs to be addressed, we can't wait for the next man to do it, the next woman to do it, we need to do it.” That's my final thought. And again, thank you so much for inviting me to speak with you.

Laura James’s related links: website / Instagram / Facebook / Bronx200

All images above courtesy of Laura James

A self-taught painter and illustrator, Laura James has been working as an artist for almost thirty years. As a child, she spent much of her free time at the Brooklyn Public Library, the only place her parents would let her go on her own. There she explored her passion for literature, photography, and later painting. Her African and Caribbean-American heritage, and a love of stories, design, and color, are all elements that have always been present in her work.

Originally captivated by the Ethiopian Christian Art form, James’s sacred work employs this ancient way of making icons and expands on the collection of stories traditionally painted in this style. James is pleased to help black people see themselves in their sacred texts, in African religions and Christianity, a place where racialized people have curiously been excluded in the west.

The youngest of eight sisters, her mother a homemaker, domestic worker and nanny, James’s secular work reflects her life, a world surrounded by women.

James’s ongoing work, The Nanny Series, abstracts images from her childhood with the use of surrealist painting and postcolonial theory to address issues of gender, work, and motherhood in the lives of domestic workers living in New York City.

For two decades James has been represented by Bridgeman Images, the world's leading specialists in the distribution of fine art for reproduction, James’ work can be seen in hundreds of publications from textbooks to film worldwide. James has illustrated two children’s books, both written by Olive Senior and published by Tradewinds Books, Anna Carries Water (2014) and Boonoonoonous Hair! which was released in 2019. Both stories are centered on empowering young black girls, and building a foundation of self-love within them.

James has curated numerous exhibitions over the past 30 years and enjoys using her organizing talents to help other artists shine. With an eye on creative solutions, collaboration, and service, she is also an arts activist, and a proud member of her community board.

Laura is currently working on what she hopes will be some of her best and most important work, a series of ten paintings around the theme of Race and Reparations that focuses on the ‘why’ more than the ‘how,’ and each piece will show how the past is still being realized in the present.

James lives and works in The Bronx, NY.