María José Contreras

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Espejo Ovalles: María José, I am grateful that Dermis León put us in touch. When you and I met at Leslie Lohman Museum of Art I immediately felt a connection and I knew that I could open up with you and that we could talk performance art from the heart.

María José Contreras: The connection was mutual! We had a profound conversation about the power of performance and, in particular, the impact of the exhibit INDECENCIA that you curated. I am glad to continue our conversation, thank you for having me.

NDEREO: Can you tell me about Talk to the Future, the performance that you presented at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City? Can you tell me about it beyond what I can read or find about this performance online? I am curious as to the essence of this action from a personal perspective.

MJC: Talk to the Future is the product of a close collaboration with the participants of the Zip Code Memory Project, a project that seeks to find artistic and community-based ways to memorialize the devastating losses resulting from the coronavirus pandemic while also acknowledging its radical differential effects on Upper New York City neighborhoods. I was invited as a performance artist to facilitate a workshop in the context of the project and to devise a performance work. The workshop I proposed, entitled Aquí/Here, invited participants to reflect about their personal and collective experience of the pandemic.

Based in embodied collective practices Aqui/Here offered a ludic yet profound way to connect with the losses of the pandemic while also visualizing the disparity of its effects. One of the core exercises was building body maps: each participant drew their own silhouette on a big piece of paper and then wrote, scribbled and drew their feelings and memories, identifying a specific part of the body where they felt that memory. The exercise was very moving, one participant drew the pain that the death of a friend caused in her chest, while another drew their community supporting them as bricks under their feet. Memories associated with the first months of quarantine appeared in a body map as a box over the head an in another as chains compressing the limbs. Body maps are a great methodology for externalizing difficult memories and sharing them through non-verbal means with others. We spent time sharing the impressions of our body maps and working through embodied practices. This was the first time many of us had time to connect with the experience of the pandemic and to share it with others.

We also worked on tracing maps of the participant’s neighborhoods with personal memories: what was your walking trajectory when you walked your dog during quarantine? Where did you see the freezer trucks used as makeshift morgues the first time? What was your deceased mother’s favorite bench in the park? Each participant traced their personal trajectories over the city map, and then we took time to listen to our stories. Many commonalities became evident, and at the same time, we realized how unique the experience of the pandemic was for each one of us. It also became pretty evident how the pandemic revealed and exacerbated the pre-existing inequalities. In our conversations the wide disparities by race, class, ethnicity, and place of residence became painful and tangible realities.

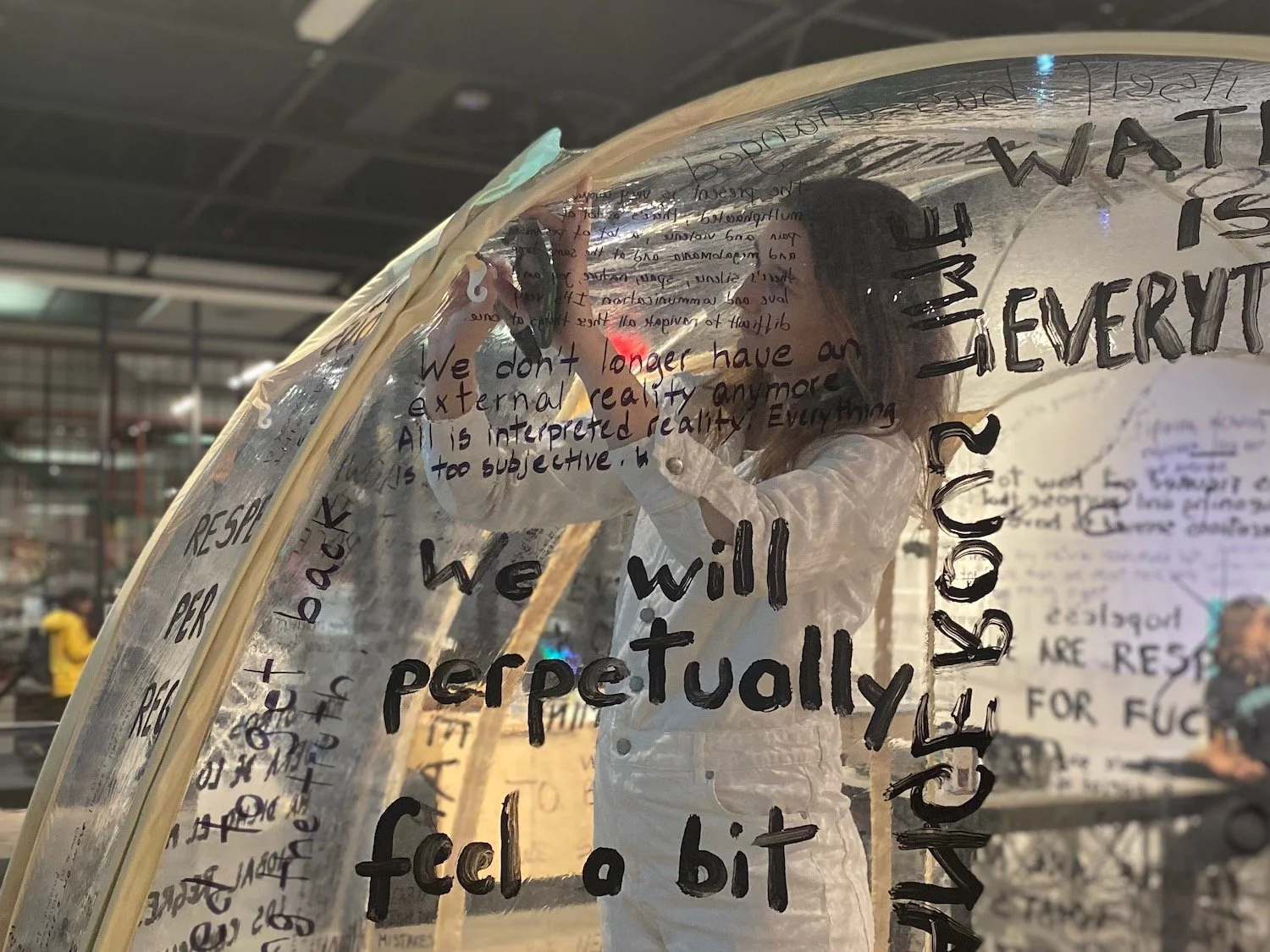

I conceived Talk to the Future as a reaction to everything I learned while facilitating these workshops. I was moved by the pervasive feeling of isolation but also by the networks of solidarity that were activated during the pandemic. We are all still pretty much processing the cascading traumatic effects of the pandemic, so I wanted to offer the conditions for a caring and careful connection for processing together. A safe space, separated from our daily vicissitudes to slow down and resonate together. Recalling the first months of the pandemic back in 2020 when people starting building walls made of plastic to hug their loved ones and reduce the risk of infection, I thought of a plastic wall. This time not between us, but between us and the frenzy of our daily lives. I recalled a conversation with one workshop participant who told me she didn’t know how she’d explain to her granddaughter the magnitude of our failure as society, “how we decided that some lives were disposable.” That’s when the idea of the time capsule hit me. Instead of asking participants about their memories of the pandemic (as we did in the workshop), I wanted to convey a future with them. When participants come into the time capsule, this transparent bubble, I ask them: “What do you want future generations to know about Covid in NYC?” The question is always surprising and unexpected. We haven’t had time to process what happened, let alone imagine a future together. In the time capsule I practice active listening. I am present with all my senses, trying to resonate with all my body with my visitor’s mood, words, visions and imaginations. When they leave the time capsule, I write down verbatim their words in the bubble. The time capsule was transparent the first day, but every day I perform, every hour I spend in the bubble I write more and more re-imaginations of the future. This is a durational performance. The number of deaths in New York by April 23rd 2022, the first day I performed Talk to the Future, was 68208. I converted that to seconds so I performed one second for each Covid victim, amounting for 19 hours. The time capsule was placed inside and outside the Cathedral of Saint John’s the Divine. I also performed Talk to the Future in Montreal in November 7 through November 11. The next performance will be on February 17th at the Museum of the City of New York. I plan to continue performing and filling the time capsule with the words of the participants. I imagine many years from now, someone will take a look at the time capsule, will read this 3D archive and somehow get a feeling of how we lived through this critical time.

NDEREO: I have worked with children for decades and I was very moved when I saw the documentation of one child talking with you in the pod that you created–while a child outside the pod looked from a distance as to what was happening inside. My immediate reaction was: what kind of future, if any, am I leaving to these children? What do those who talk with you as part of your performance envision beyond the mess in which we are all in?

MJC: Talk to the Future, as the title says, is exactly about that: imagining together what future we are leaving to next generations. Who are we doing the performance for: is it for the participants that come in the time capsule? Is it for me? Is it perhaps for the children in the photo? Or maybe for a futurist multispecies assembly of beings that will read our words as hieroglyphs?

I imagine that the most important spectators of Talk to the Future are future generations, maybe those that are not even born yet. Talk to the Future somehow twists the linearity of time. I fantasize with someone finding the time capsule 100, 200 years in the future.

An older lady came inside and told me that she had lived during the hippie revolution and that she had been an optimist all her life, but that after seeing how people reacted to the pandemic, not caring, not being able to wear a mask to protect those that are more vulnerable, she was, for the first time in her life, pessimist about the world her grandsons would inherit. She cried. And I cried with her.

Another person told me that the only thing she would say to future generations was, “don’t judge us, we did the best we could.” The futures imagined are as multiple as the people that have participated in the performance.

Coming back to the photo you are mentioning. Several children come in the bubble. I listened with amusement to their thoughts. One that was particularly striking was a young boy who looking directly into my eyes said: “future generations will be lucky if they still exist”.

NDEREO: It is clear to me how Covid has revealed systemic oppression and exploitation. This applies to the institution in general and to the work that needs to be done from within. I admire the legacies of people like Angela Davis, Marcella-Althaus Reid, Robin D. G. Kelly, and bell hooks because they have made sure to talk to about class. I find that missing within the arts, including museums and galleries where conversations on race, gender and sexuality do not address issues of class. Did any of this surface in your conversations with people during Talk to the Future?

MJC: Coming from a Latin American country as Chile where class, more than any other factor, determines the opportunities you will have, the education you will get and the health care you will access, I can’t avoid but thinking in terms of the oppressive system of classes. When I first came to the U.S. I was surprised that this didn’t seem an issue that received so much attention. Of course, oppressive systems are always intersectional, but I agree with you that issues of class are usually missing in the arts here in the North.

The Cathedral of Saint John the dDvine is a very interesting place in NYC. Many different people come inside the Cathedral: tourists, religious folks, LGTBQ+ communities and students. But there’s another population that comes to the Cathedral but not necessarily come inside. Every Sunday there’s a pantry line that provides food to people in need, the Catheral also has a clothing closet that provides clothing for people returning to the workforce. I wanted to listen to this community too. So somedays I placed the bubble inside the Cathedral, or in its front steps but I also placed it at the Sunday pantry line. The worries and memories of those that are marginalized from society are completely different from the stories I heard from those who came inside the Cathedral. The fear of not having food to eat, of seeing their friends die in the streets, of not knowing how their estranged family members were doing. Many told me that their hope for future generations was that no one suffered from hunger.

Working in non-institutional settings, in the streets, and particularly in vulnerable communities is a priority for me. In my work I try hard (and not always succeed) in not reproducing systemic systems of power and reaching out to those that take the worst part of our unjust society.

NDEREO: Chile has been such an epicenter for performance art–well, Latin America has been a cauldron of performance and action-based work. During our meeting at Leslie Lohman Museum of Art, I spoke about the imperative need for performance art to remain fugitive. I remember you nodded your head as if assenting. Any comments about this?

MJC: As you mentioned in our conversation, performance art is an ephemeral practice that resists its commodification. And I agree. Performance art may leave traces, may be documented but it is hardly exchangeable as a good, or an “artwork”. Of course, late capitalism has been very effective in cannibalizing whatever resists to join the neoliberal game and performance art is not an exception. Performance art has sometimes been whitewashed to fit in museums and galleries, or to fit in university curriculums. I believe there’s space for all types of performance and that each artist or creator needs to understand where and how they want to operate withing the system. For me, the beauty of performance art is in the street, the direct contact with participants, the possibility to resonate, even just for a moment, with someone you don’t know. Most of my work occurs in the streets and looks to encounter other people. I have also performed in institutionalized contexts, but the heart of my creative practice is in the streets.

NDEREO: I am trying to keep this conversation brief, as I know that everyone needs time to recover from the pandemic and to nurture life from within, yet there is so much I would like to ask. I am wondering what moves you when it comes to performance art? I have a soft spot for the Latin American generation of the 1980s and 1990s when the arts were not quite yet such a capitalist industry. I am listening.

MJC: I come from theatre. I have worked as an actor and director for many, many years. I still sometimes work devising theatre pieces. I came to performance art because I started to feel the need to reach out to audiences that are not theatre spectators. One crucial moment was in 2011 during the huge student protests in Chile that demanded a radical overhaul of the neoliberal education system. Our current president, Gabriel Boric, was one of the leaders of the movement at that time. I was teaching at the University and the students refused to go to class in adherence students’ movement’s demands. One week before the final exams date, students decided to come back to class. The university leadership told the faculty that we had to keep the same final examinations dates, and the same “assessments standards and criteria.” I was shocked! The movement was like a tectonic shift in the national political scenario and they were asking us to continue as if nothing had happened? I was teaching a movement course at the School of Theatre. I sat with my students and told them, “we will decide together what our exam will be about, and what our assessment rubric will measure.” I asked, “what’s important for you now? What are the urgencies of this time? How does a course as movement for actors serve and address the issues that compel you? After a couple of days of fruitful discussions, we decided to do a 24-hour performance in one of the main squares in Santiago. We invited 24 teachers to come to the square and teach us something for 45 minutes. After the “class” students would translate what they learned into movement and improvised choreographies. Our list of teachers included the most disparate persons: a teacher of Mapudungun the language of the Mapuche Indigenous People in Chile, an older lady that taught us how to make a cake without an oven, a dissident woman that taught us how to kiss. We stayed in the square welcoming our teachers and then translating what we learned into movement. Passers-by joined our classes and then watched our embodied translations.

Thanks to my students, I learned the power of performance in the public space. I became addicted to reaching audiences that would never come to see a theatre play. I became addicted to the feeling of connection with people that you don’t know. I became addicted to the political impact of performance in the public space. An impact that may be subtle, minor, and yet so so powerful.

NDEREO: Can art be imagined/reimagined outside the capitalist model? Can performance art escape the tentacles of the art machine that co-opts and commodifies everything it can? I dream of networks of care among creatives. I dream of networks of support and love in the arts.

MJC: I think networks of care among creatives already exist. Maybe not as extended as we’d like, but I do feel that there are networks of solidarity and mutual care. Being together with other creatives and collaborating is one of the things that matters the most to me. A great example of a caring network was the work of the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics at NYU. As you well know, there was a tight family of “hemisexuals” that collaborated transnationally in creative, joyful, and fruitful ways. The experience of the Encuentros was crucial in my understanding of transnational collaboration and in building kinship with other activists, artists and scholars. So many beautiful and powerful things were born in that Encuentros. I speak in past tense because I’m not sure what the plan of the new leadership is. I hope we can re-activate those amazing networks.

To me, performance art is an incredible way to be together in a caring and careful environment. And this is revolutionary. As you say, the art machine co-opts and commodifies everything it can, but I’ve found in performance practices an effective antidote for that. Performance also allows us to infiltrate in institutional settings and subvert from the inside the hegemonic oppressive systems that are usually in place in these contexts. In my work as a Professor at the University in Chile and now in the U.S., performance is my favorite tool to mobilize critical thinking, feminist pedagogies and embodied knowledge.

NDEREO: Thank you for this conversation. Anything that you would like to say, please go ahead.

MJC: Thank you for this amazing opportunity. I hope we can continue our conversations!

María José Contreras is a Chilean multidisciplinary artist/scholar working in the international field of theatre and performance. She is Associate Professor at Columbia University. Her creative practice and scholarship aim to transform civic and academic spaces and collective imaginaries. Her engagement with decolonizing theatre-making, teaching, and research practice is recognized in The Twenty-First Century Performance Reader (London, Routledge, 2020), an international volume featuring the 73 leading global artists working with innovative approaches to performance. Contreras’s devised theatre pieces, urban interventions, and performances have been presented in important venues and festivals in the US, Italy, Ukraine, Chile, Argentina, Canada, France and Brazil. In addition to numerous articles published in several languages, she recently co-edited two interdisciplinary volumes Cadáver exquisito: tres experiencias de investigación performativa en Chile (Oso Liebre, 2020) and Women Mobilizing Memory (Columbia University Press, 2019). She is currently working on her manuscript Rigorously undisciplined: decolonial approaches to performance research.

All images above courtesy of María José Contreras

María José Contreras / links to work and publications: Website

Contreras, Maria José (2020). "The body of memory: Maria José Contreras performance practices in the Chilean Transition". En Brayshaw, T.; Fennemore, A.; Witts, N. The The Twenty-First Century Performance Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 131-141. To access this piece click HERE

Contreras, Maria José (2019). “Aquí. Performing mapping practices in Santiago de Chile” en Altinay, A.; Contreras, MJ.; Hirsch, M.; Howard, J.; Karaca, B.; Solomon, A. (eds.) Women Mobilizing Memory. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 152-171. To access this piece click HERE

2017. “A woman artist in Chilean Neoliberal Jungle” en Amich, C., Varney, D. & Diamond, E. Performance, Feminism and Affect in Neoliberal Times. Londres. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 239-251. To access this piece click HERE