Ruth Montiel Arias

Nicolás Dumit Estévez Raful Ovalles: Ruth, you participated in the video screening which Andrés Senra and I organized for BAAD! as part of Andrés’s Fellowship at The Interior Beauty Salon. The title of the program was We were Never Human. Visiting your online archive, I see that one of your projects deals with concept of “humanity” in relationship to gold. Can you talk about this?

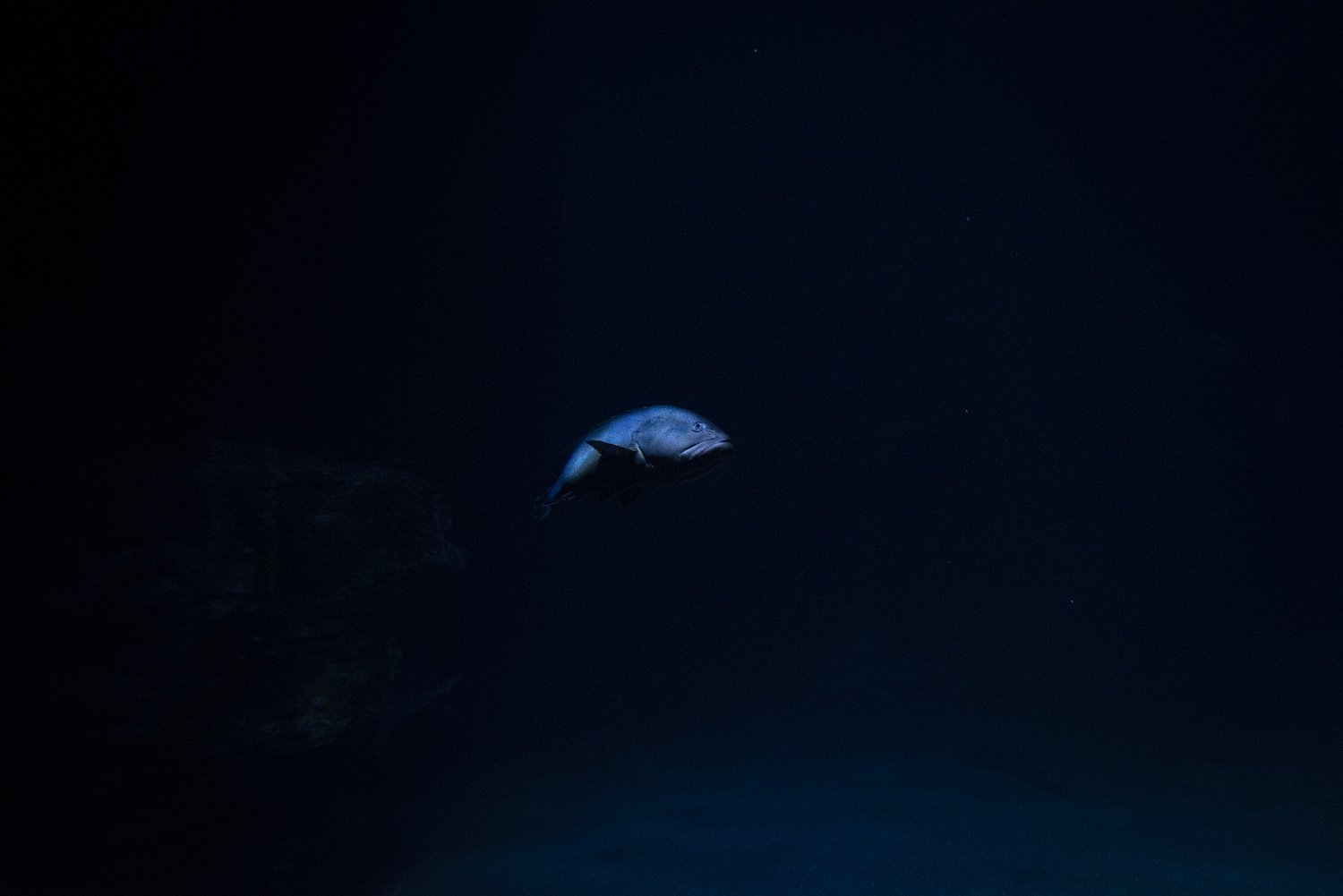

Ruth Montiel Arias: The project you are referring to is Sin oro no hay hombre (Without Gold there is no Man), which I carried out between South Africa and Perú, one the cradle of humanity and the other the cradle of gold. In it I focus on the definition of "humanity" that is linked to the evolution of the species itself, and how this generates a change in behavior. “Humans” discover gold and decide to use it as the material that would support the global economic foundations, and with it the plunder, torture and destruction of people and territories that harbor this metal. South Africa is the area called the Cradle of Humanity, since there is where the first adult Australopithecus was found in 1936. Without Gold there is no Man begins here, since this area is full of mines that have been originally excavated to search for gold, not for archaeological or anthropological purposes. This came later in a process that led to finding the origins of humanity. My project shows the dark perspective as well as the other side; the people who are wise, generous, empathetic and connected to nature. Such is the case of the women I met in Perú and South Africa during the development of the project, who demonstrate our capacity for change and hope through their struggle.

NDERO: I admit that your photographs of people with cats caught my attention…and more than my attention, they spoke to my heart. Although I do not have a way to prove it, I feel that I have been a cat before. Can we include some of your images of “humans” sitting with their adored felines and can you tell me about the narratives behind these visuals?

RMA: It is an honor that these photographs touched your heart and I am very happy about it. I collaborate with a Cat Shelter when I am in my town and I see first-hand how volunteers work hard to rescue, cure and care for the animals that come into their hands. They not only put all their time and energy, but also financial and material resources. They mourn every loss and celebrate every life they have been able to save with all the humility that characterizes anonymous people in any town.

I started photographing rescued cats so that the organization helping them could put them on their social networks and find families for them, but over time I wanted to pay a small tribute to these people who care about the ones that hardly anyone looks at. This is how Callejeras was born, a small series of portraits of volunteers with rescued cats, who have become part of their families and the stories that accompany them. The beauty of this work is that the animals portrayed have a happy ending, which is not very common in my work.

NDERO: I gave up meat more than a decade ago. I was teaching a class on food and eating at Transart Institute in Berlin, Germany, and through the research I was doing learned about the atrocities inflicted upon non-human animals for the purpose of generating meat. I still eat fish, and my intention is to pull this out of my diet. The fish industry is as atrocious as the cattle, poultry and pork ones. I find it difficult to start a conversation with the purpose of having people see the outcomes of the choices we make regarding what and who we eat. Any words of wisdom as to how to generate a dialogue about this topic that does not create more polarization than the one our societies are currently facing?

RMA: What a difficult question, Nicolás. The basic problem is who is the person receiving the message and how is the message received. In my humble opinion, I think it is important to know how to detect if that person is really interested in knowing about it or, on the contrary, it can make them feel bad. It is also interesting to know what materials interest them the most, that is, sharing tools that we know or intuit may matter to them, whether through cinema, music, literature, art, philosophy, etc. Fortunately, more and more, anti-speciesism is in many of the fields in which the human being are developing. I also see it as equallly important to have patience and be willing to answer questions that, in most cases, we have answered many times.

NDERO: I am fully aware of the “human” suffering involved in food production. There are the mostly undocumented farm workers in the U.S. (and in other countries) who are exploited for the purpose of producing what we eat. There are also the small and independent farmers who have depleted the soil seeking to keep themselves afloat. In some conversations I have had I have heard people discount the suffering of non-human animals as they compare what some “humans” go through in the food business. I personally believe that the suffering of the two, human and non-human animals, is interconnected–intrinsically weaved together. Have you approached this in any of your projects?

RMA: This is a topic that I haven't worked on yet, since right now my focus is more on non-human animals. However, it is a reality that I know. In Spain the same thing happens in many slaughterhouses, hellish places where humans are exploited and animals are killed. Many of the workers in these places are migrants in conditions of exploitation or semi-slavery. In these cases, we must be inclusive in the struggles and fight for the rights of animals as well as for human rights. In these cases, speciesism, racism, sexism, classism and abuse of power are separated. How can we not fight against that in a transversal way? There are other areas of animal exploitation for food, such as some farms or production chains where workers are more protected under labor agreements since unions, at least in Spain, continue to have some presence. In these cases, animal suffering prevails over human suffering. I enclose an article (in Spanish) that speaks precisely about human exploitation in slaughterhouses, I think it is very necessary to read it : Miedo, accidentes laborales y racismo, la dura realidad del trabajo en los mataderos españoles.

NDERO: It is taking me longer than expected to align my ethics to the work that I do and the works that I curate. Many performance art pieces have traditionally been inspired by rituals. I have found myself dealing with the dilemma of not wanting to impose my ethics on others and, at the same time, not wanting to perpetuate more suffering. There are performances and other artworks which utilize fur, feathers, blood, and even live animals. Perhaps it is a matter of kindling awareness and letting others decide. What are some of the ethical issues you have had to deal with as a creative?

RMA: The biggest ethical problem that I have had to deal with in my work is treating the animal with the greatest dignity possible, especially in photographic documentation works that show the exploitation to which they are subjected. In the field of photojournalism or photodocumentary, as with humans, we have to put our moral values before continuing to perpetuate what we reject and we can see this very well in photographic works linked to armed or migratory conflicts where the majority of photographers continue perpetuating a photographic language that does not consider the dignity of those people photographed. I know that it is an eternal and difficult debate, but I believe that we must change the codes and build new stories that move away from what continues to perpetuate what the system wants. Returning to animals, today we should ask ourselves if there is another possible way, without having to use any animal, to represent everything we want. Those of us who work in the artistic field have all the necessary tools to avoid using anything that comes from animal exploitation.

NDERO: I totally agree with you that, as an artist, I have the tools that I need to avoid using non-human animal elements in my work. Talking about non-human animals and the current climate disaster, during the Covid pandemic, many of those in New York City with second homes and financial resources fled the place and came back after nurses, supermarkets cashiers, bus drives and Others deemed as essential workers did the “dirty” work: nourished the living, tended to the sick and buried the dead. What would you say might be the future of cities in a planet facing the ecological mess we “humans” have set in motion?

RMA: I believe that cities, as they are structured today, are the worst place to face any ecological crisis and, as you indicate, those who suffer the most are people with fewer resources. Cities are the nuclei of overflowing consumerism and therefore the spaces that more people demand in order to make the economic wheel work. Rural areas that are exploited ad nauseam are uninhabited, making them uninhabitable due to the contamination of their waters due to fertilizers from the agricultural industry or the excrement of animals in livestock exploitation. I also believe that these dynamics are generated to make the working and poor class–more so in cities, as you say–to do the "dirty" work that the upper class is not going to do; but it is also a way of hooking the less favored classes, thus making them dependent and thus continue to feed capitalism, which in the end is the essence of most of the problems of humanity and therefore of the planet. Cultural critic Fredric Jameson said that "it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism." Well, it is up to us to change this paradigm and imagine the end of capitalism so that the beginning of a fairer world, whether in cities or in towns, can one day become a reality.

NDERO: In this conversation I have been critical of us “human.” I would like to balance our exchange because there are many of us envisioning new ways of being that are more harmonious with our planet. How would you say can the arts and artists can be part of this balancing wave?

RMA: We artists also have to stop looking at our navel to attend to everything that surrounds us and learn from those people who, as you say, are more in harmony with the planet: from a peasant from Upper Perú, to a doctor in Ethiopia, from a 20-year-old Iranian woman to an older Palestinian, from a Native American in southern Canada to an African American in Spain. We are not something special and different from others, we are exactly the same, only that we express ourselves with other tools linked to the field of the arts.

NDERO: Can the overwhelming emphasis that the art industry (aka art world) puts into production, fame, ego-worship, branding… be transformed by a cadre of creatives envisioning more communal ways of working? Any ideas as to how a more compassionate art in the service of the common good can become possible?

RMA: I have no hope when it comes to the art industry precisely because it is another industry greased within a neoliberal system that gives money to a few while many live in a very precarious way. In the case of art, as you point out, the currency of payment is the ego, even if it keeps our stomachs quite empty. I believe that art itself has no obligation to be one thing or another for society. In any case, it would be the artists who, if they wish, can use the tools and codes of art for a common good. There are many artists who use their work to think of transmitting something good to society. However, it is strange to see such artists within the system. When the circuits of the artistic system make room for a work or an artist of these characteristics, the message it transmits is deactivated and domesticated, so it will serve little for the common good. So it's time to look at dissidence or at the independent circuit to find a more committed art. Although it may be that, from time to time, something slips.

NDERO: What can creatives learn from non-human animals?

RMA: I believe that everyone can learn, whether we are creative people or not, and I would tell you that the first thing would be to stop and breathe. I feel that we already know many things that animals know, the only thing is that we have lost almost all that learning, so we have to observe them to reconnect. What I can tell you is what I learn when I stop and start observing an animal. I feel that it casts a spell on me so that in some way I realize that they are there and that they are just as or more necessary than us. With animals I experience freedom and the privilege of having someone stop and give me a little of their time or attention. I can see in them a liberation from the mundane ties that we humans have to material things. In the case of animals that are part of human families and therefore are treated with respect, affection and protection, I admire their magnetism and the tranquility with which they navigate life. But I also come across many animals in situations of exploitation and suffering, and from them I learn how important and necessary it is to fight to abolish the injustice to which they are subjected.

NDERO: As I mentioned before, I have been a cat. What about you?

RMA: I don't think I have been just one animal, rather I think I have been a bit of many.

NDERO: Thank you for what you do to bring awareness to the conditions that create so much unnecessary suffering for non-human animals. Any last words?

RMA: First of all, thank you for this interview, it's one of the best I've had in a long time. I hope I have lived up to it despite being a sparing person in words. I want to congratulate you for the space you have created with The Interior Beauty Salon and the community that you are forming around it, spaces like yours are very necessary in these turbulent times we are experiencing. And I wanted to close by saying that another world is possible if we really believe in it and work to make it a reality, although we probably don't see it, but we can leave the land plowed and planted so that those who come after us can water it.

NDERO: Thank you so much, Ruth, for your kind words. I hope to meet in person soon to talk some more about what you do and to sit in your presence. In the meantime, The Salon’s doors are open to you.

RMA: If all goes well maybe we can talk in person, as I have a trip scheduled to New York in 2024. It will be a real pleasure to spend time with you and visit The Interior Beauty Salon. I send you a big hug and a million thanks.

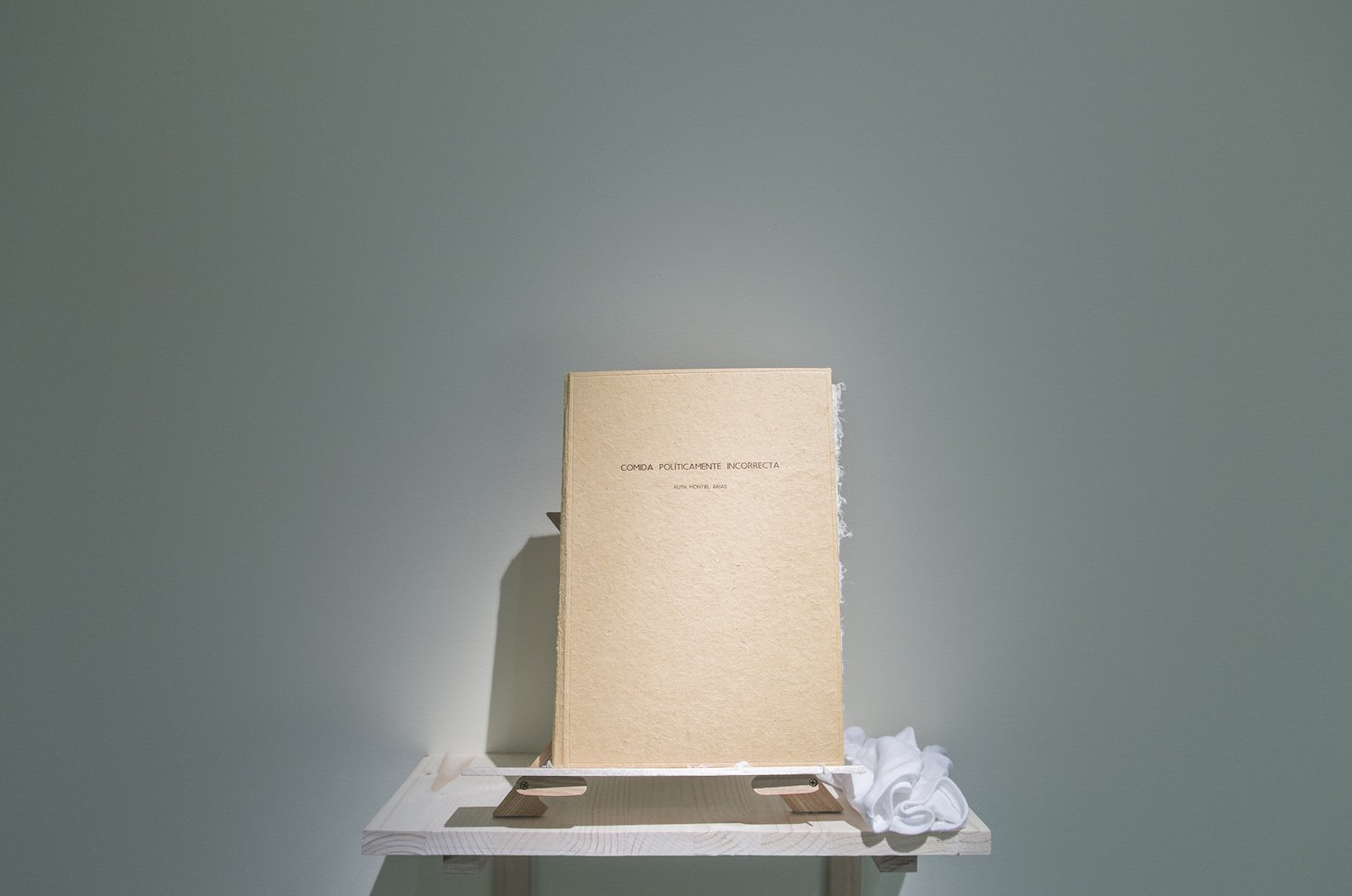

Ruth Montiel Arias, Palmeira (A Coruña - Spain), 1977 / Ruth graduated in Applied Arts from the Pablo Picasso High School of Arts in A Coruña. She completed a Master of Corporate Identity at Pompeu Fabra UPF University in Barcelona (2005-06), and the Master of Photography EFTI in Madrid (2010). Her projects investigate the human relationship with the natural territory, and its derived conflicts of domination and animal, social and environmental oppression. Her photographs have been shown and published in different national and international media and newspapers, as well as in specialized publications. She is the author of BESTIAE, (self-published, 2020) and El 2% , published in 2021. Ruth’s work has been exhibited in cultural institutions such as the Centro Cultural de España, Lima; Landkreis Galerie, Germany; Museo de la Memoria, Argentina; La Casa Encendida, National Chalcography, Círculo de Bellas Artes, Conde Duque Cultural Center, and Matadero, Madrid; Cristina Enea Foundazioa, Donostia; and Cidade da Cultura, Santiago de Compostela. She has also exhibited in galleries in Madrid, such as Galería Zero, Galería Liebre, La New Gallery, and Noestudio. Ruth has exhibited as well at international galleries such as Galería Moproo, Shanghai; and Galería Ruby, Buenos Aires. Ruth’s work has been awarded numerous grants and residences, including the best photo essay lifestyle at the Ottawa International Vegan Film Festival (2019), and a VEGAP Creation Grant (2017). She was a finalist for Fotopress La Caixa (2015).

All images above courtesy of Ruth Montiel Arias

Ruth Montiel Arias / Related links: Website / IG / Vimeo / YouTube / Twitter / Contact